A male friend of mine once said he thought women shouldn’t get upset at the term “mankind.” Women should know we are included. I said, “When Neil Armstrong said ‘…one giant leap for mankind,’ I know he meant all of us. Women know how to include ourselves in exclusionary language. But imagine the mental gymnastics you, as a man, would have to do if the words were ‘One small step for woman, one giant leap for womankind.’ Different feeling, right?”

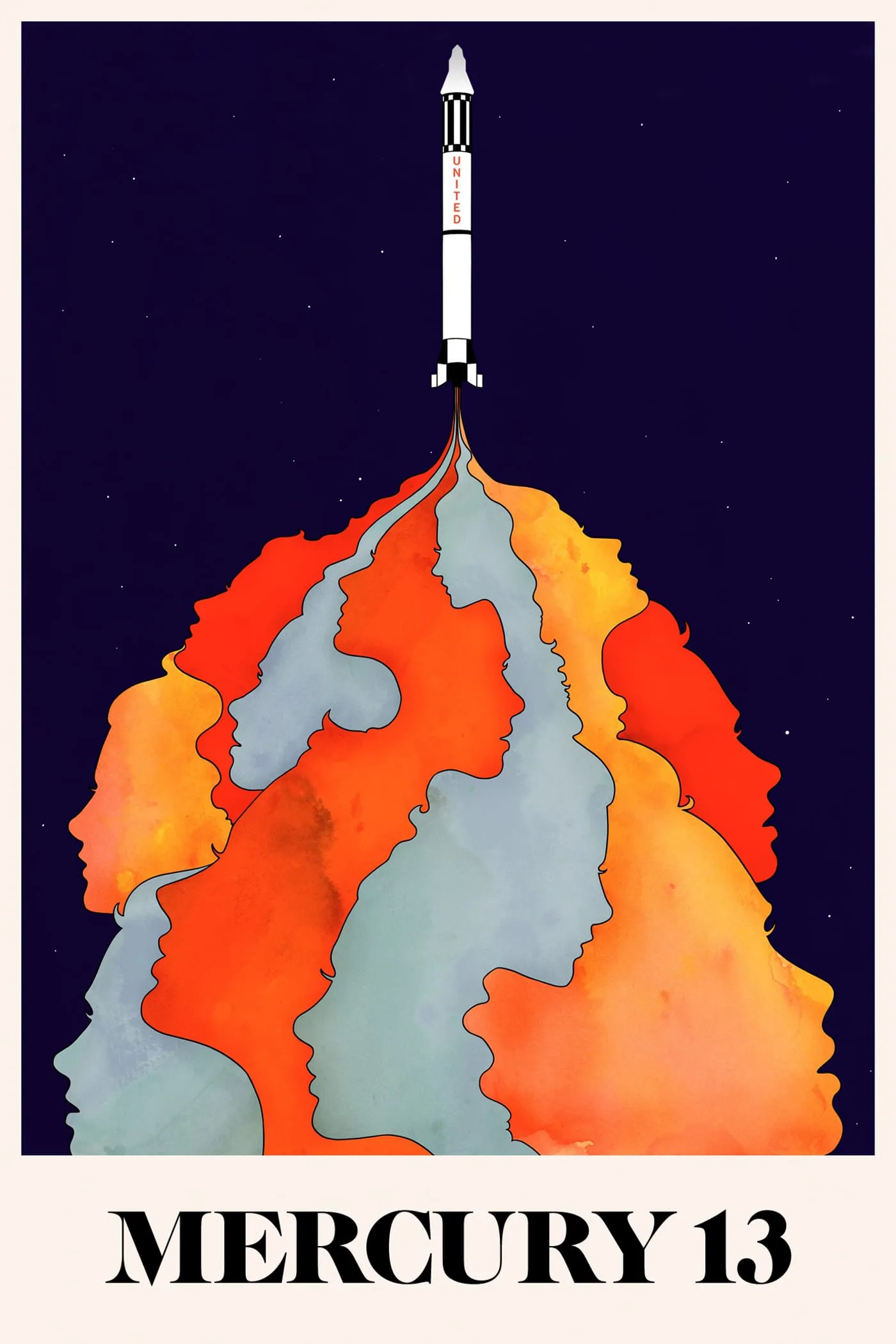

Since this guy is a friend, and not a hostile drive-by on Twitter, we had an interesting discussion about it. He said yes, if he heard “one small step for woman” he would never assume he was included. I thought about this conversation a lot while watching the Netflix-produced documentary “Mercury 13,” about the 13 female pilots who underwent astronaut training in the late 1950s/early ’60s, in tandem with the first astronauts of NASA’s space program. In a couple of separate moments, the documentary takes an imaginative alternate-history leap, showing the footage of Neil Armstrong descending the ladder onto the powdery surface of the moon, accompanied by a female voice broadcast back to planet Earth: “That’s one small step for a woman. One giant leap …” How would gender perceptions have changed if it had been men and women getting those ticker-tape parades on return? What a vast opportunity was lost.

Co-directors David Sington and Heather Walsh know this territory well. Their 2007 documentary “In the Shadow of the Moon,” made Apollo missions feel fresh, gripping, exciting. The two know how to weave together the vast amount of extant footage with current interviews, without sacrificing emotional buildup and tension. They use the same style in “Mercury 13,” including a couple of poetic “devices,” some which work better than others. Utilizing current-day interviews with the surviving members of the Mercury 13, interspersed with archival footage (some familiar, some not), “Mercury 13” details the attempts of Dr. William Randolph Lovelace, flight surgeon and NASA advisor, pioneer and visionary, to create an astronaut testing program for women. This was an independently funded program. As the male astronauts were going through their battery of tests, the women went through the same, only with zero fanfare. Lovelace saw no reason women shouldn’t be allowed to be astronauts. In a couple of cases, the women tested higher than the men. This was especially obvious in the tests involving the sensory deprivation chambers. Statistically, the men crawled out of their skin, but the women could stay in the chambers indefinitely. One fell asleep, floating in the water. One woman lasted a record-breaking nine hours. Where the women ran into trouble was jet certification, one of the requirements to even qualify. In a classic Catch-22, none of the women had jet certification since jet training was not available to women. When NASA got wind of the program, they brought it to a shrieking halt. Women astronauts were treated as an adorable joke. (In a huge propaganda triumph in 1963, the Russians sent the first woman into space, Valentina Tereshkova.)

At a brisk and efficient 78-minutes, “Mercury 13” is engaging, yet sadness and anger seeps in as it progresses. We may not have known the story in its details, but we all know how it ended. We know these feisty smart daredevils (one of whom had eight children) were denied the chance to compete with men for spots on those initial missions. As far as the “story” that has been passed down through popular culture: since it was men who went to space, it was always men who were meant to go. “Mercury 13” destroys those assumptions. The Mercury 13 were in the news at the time. There were even Senate hearings about whether or not women should be included in NASA’s astronaut training programs. In her testimony to the Senate Committee, pilot Jerrie Cobb stated, “We ask as citizens of the nation to be allowed to participate with seriousness and sincerity in the making of history now, as women have in the past.” It wouldn’t be until 1983, when Sally Ride became the first American woman to go into space, that the completely arbitrary gender barrier would be broken.

All of the women interviewed are senior citizens now, but they sound just like the cocky John Glenn or Alan Shepard or Gordon Cooper in those famous press conferences in the 1960s. Rhea Woltman, a white-haired woman wearing a wide-brimmed two-toned hat and red lipstick, says, eyes sparking with steely competition: “Jerrie Cobb was a good pilot but I could fly as well as she could.” Gene Nora Jessen, reminiscing about her childhood dream of aviation, said, “I didn’t need a lot of encouragement. I was rarin’ to go.” As heartbreaking as the cancellation of the program was, it didn’t stop any of them. Some went on to be test pilots. One taught herself aerobatics. One was so angry at the prejudice that kept her out of the space program she went on to be one of the founding members of the National Organization of Women. The inroads women have made in aviation since the Mercury 13 are given short shrift, appearing mainly as a brief epilogue. Some time is given to Eileen Collins, the first women to pilot the space shuttle, who explicitly referenced the Mercury 13 in her speech accepting the command, and invited all of them to the launch). There’s a catharsis of emotion watching these now elderly women screaming and crying as they watched the space shuttle blast off, knowing a woman was at the controls.

Margot Lee Shetterly’s book Hidden Figures: The Untold True Story of Four African-American Women who Helped Launch Our Nation Into Space (and the ensuing film adaptation) shined a klieg light into a well-known and picked-apart era in America’s history, revealing the key roles a group of African-American mathematicians and engineers played in getting John Glenn into orbit, in getting Neil Armstrong down that ladder. There are more stories out there to be told. In one of the more poetic moments in “Mercury 13,” footage of the billowing banner saying “Welcome Home Neil” transforms into “Welcome Home Janey.” Anyone who would bristle defensively at such a sight is part of the past, not the future.