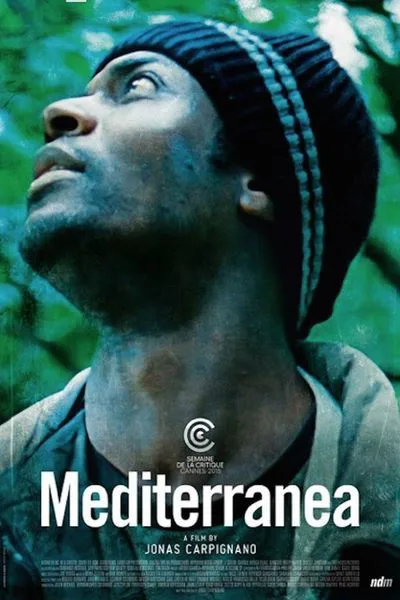

Where “Black Lives Matter” has become a rallying cry in the U.S., Jonas Carpignano’s sharply crafted “Mediterranea” voices a counterpart for African immigrants in southern Italy: “Stop shooting blacks!” That chant emerges at the dramatic apex of the multi-nationally funded feature, which otherwise offers a deliberately muted, finely textured account of the ordeals many Africans endure both before and after voyages to Europe in search of better lives.

The film’s subject is, of course, incredibly timely. If recent media attention has focused on the waves of desperate migration from the Middle East, the flights from Africa depicted here are no less perilous and dramatically charged, resulting in Mediterranean drownings and occasional racial strife such as the 2010 riots in Rosarno, Italy, that drew writer-director Carpignano to the area in its wake.

With an African-American mother and an Italian father, Carpignano was well-positioned to examine the situation of Africans in Italy. He first turned his investigations into a short, “A Chjána,” which won him a Critics Week prize at Cannes and a place at the Sundance Lab, where he developed it into the current feature.

Carpignano has noted that the stories of migratory hardships in the media recently concern two types of migrants: those fleeing war or persecution, and those seeking better economic opportunities. The Africans he focuses on in “Mediterranea” belong to the latter group, which he compares to the mass immigration of southern Italians to the U.S. in the early 20th century. The root causes of the two movements may have been the same, but as he also notes, the earlier migration was better organized legally and logistically than the more chaotic exodus from Africa in this century.

While researching “A Chjána,” Carpignano had the singular good fortune of meeting an African immigrant named Koudos Seihon, who helped him enter and understand the immigrant world and became his lead actor in “Mediterranea.” Striking and charismatic, Seihon is a natural screen presence blessed with both power and subtlety. It’s hard to overstate his importance to the film.

He plays Ayiva, who leaves Burkino Faso aiming to create a better life for his wife and daughter by finding employment in Europe. With his quirky, rebellious friend Abas (a strong performance by Senegalese actor Alassane Sy) and other hopefuls, he ventures through the punishing deserts of North Africa and makes a hazardous crossing of the Mediterranean.

Reaching his goal, though, doesn’t mean a dream fulfilled. Southern Italy contains both problem-plagued opportunities and lurking threats. Along with some of their counterparts, Ayiva and Abas find work as fruit pickers, which, while offering at least some remuneration, entails various sorts of difficulties including blatantly unfair treatment by some of the Italian bosses.

Interestingly, the main boss invites the African workers into his house, introduces them to his family and feeds them a big Italian farm dinner. The man’s mother instructs everyone to call her “Mamma” and chides the Africans in maternal fashion for not taking off their hats at table. At the same time, Ayiva begins to strike up a friendship with the boss’ daughter. These passages of hospitality from some Italians contrast nicely with the hostility that will be displayed by others later in the story.

Apart from their interaction with Italians, the film depicts the Africans’ lives as migrant workers, which includes friendships and animosities, boredom and temptation. The African women that the men find in Italy can be good-time partiers or offer professional relief from their loneliness, which is not erased by their ability to talk with their families by Skype, as Ayiva does. These women, in any case, form their own discrete subculture with appropriate idols and anthems: the music of Rihanna, especially the song “We Found Love” (with its evocation of a “hopeless place”), is omnipresent.

The presence of the Africans eventually inflames the tempers and bigotries of this rustic backwater, resulting in the violence that will provoke a riot and chants of “Stop shooting blacks!” But this doesn’t seem to be point of the story, just another episode in the immigrants’ long, sometimes bumpy odyssey.

Overall, the film employs a rather anecdotal, loose-leaf approach to narrative, which enhances its feel of anthropological accuracy but not its dramatic power. We emerge feeling we’ve been escorted into a real and fascinating world rather than engaged by a truly compelling and focused story. Partly, this is a function of the film’s emphasis on its beautifully realized verité-like surface, which comes across somewhat as an end in itself.

Such meticulous, fashionable naturalism belongs to many European art films and not a few Sundance products (Carpignano, gifted cinematographer Wyatt Garfield and editor Affonso Gonçalves all worked on “Beasts of the Southern Wild,” whose director, Benh Zeitlin, co-wrote the score of “Mediterranea”) and it’s not always fortunate, resulting in films often destined to reach only elite audiences in festivals and art houses. Given the subject of “Mediterranea,” it could have benefited by an approach that would attract a wider viewership.

That said, it’s a very impressive and valuable first film on numerous levels. Carpignano, Seihon, Garfield and their collaborators are surely talents to watch.