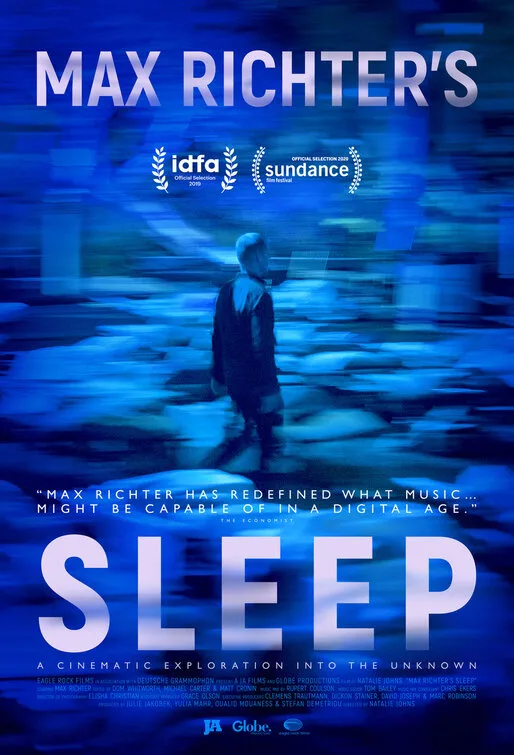

“Max Richter’s Sleep,” which is being given its online premiere on MUBI on March 19th in recognition of World Sleep Day, is part documentary, concert film, romance, and existentialist meditation on the world around us. It explores our symbiotic relationship with nature and our experiences, both conscious and in dreams. By examining the way we experience music, especially communally, it looks at how we consume media both aurally and visually at a frightening pace—as a race, we’ve never needed to slow down more, but relaxing and rewriting our brains to look at music in a mindful way feels antithetical in a culture where the first thing we do after experiencing media is jump online to argue about it.

Natalie Johns’ refreshingly patient film looks at the evolution of neo-classical composer Richter’s 2015 concept album Sleep and is centered around an outdoor performance of the work in Los Angeles’ Grand Park. While an open-air concert doesn’t sound out of the ordinary, it just so happens that Sleep is eight hours and twenty-two minutes long (roughly a traditional “good night’s sleep”). Richter designed the composition to be a fresh approach to how we traditionally listen to music and he encourages the audience to sleep while listening. Instead of rows of uncomfortable seats, there are cots; 560 to be exact.

But the performance is just a Trojan Horse as we’re taken inside Max’s wonderful world, privy to the tale of romance and dedication that is his relationship with partner Yulia Mahr. An artist and filmmaker in her own right, Mahr helped conceive the project based on ideas that had been percolating inside Richter’s head for decades previous. Richter describes the work as a “quiet protest” against the rigorous speed of modern life; it’s apparent that Richter and Mahr see the live performances as the culmination of their work. And while there may be self-indulgence there, the picture painted of Richter is an intelligent and rather cuddly family man with a great sense of humor and a sheer fascination with music.

With that, we’re treated to spectacular views of the Oxfordshire countryside and their secluded home, as Richter focuses on his music while struggling to make ends meet for the family, with Mahr suffering from malnutrition. He explains that he sees everything through music, saying, “You’re just creating something you want to hear that no one has written yet”. And while his primary instrument is a grand piano, he also explains his interest in electronic music, inevitably kickstarted by Kraftwerk and their 1974 LP Autobahn. The relevance here is that Sleep is a blend of the acoustic and the electronic, with synthesizers a necessity to reach the extremely low frequencies the piece requires.

For decades, we’ve used the concept of falling asleep during something as a major critical point, a failure for the film or album to engage. But there has been a growing movement that doesn’t scold either the media or themselves for falling asleep; instead, it’s almost a ritual, and many people have movies or records they put on to fall asleep to. So it’s only natural that someone would create a work based around that, one that tries to connect the conscious and unconscious worlds. Richter talks of deeper concepts at play, ruminating on our existence, our origins, and the meditative properties of the natural world. Richter essentially gives his audience permission to do whatever they want during the performance, within reason of course. What’s fascinating is that there’s no measurement of success given, it’s more around the individual and communal responses rather than any traditional achievement.

While the concert is in the middle of downtown Los Angeles, Johns’ film does its best to accentuate the nature around it. The stage lighting imbues the surrounding trees with a hallucinatory blue while the narrative extrapolates itself to show the environments of concertgoers as they talk about their experience, injecting a smidge of Malick-esque poetry such as a trio of cormorants lazily gliding over the choppy Californian surf. It may seem like a simple moment, but it’s perhaps the most thematically relevant image in the film, with Richter’s music seducing us and allowing us to be absorbed into the natural world. The picture also features some beautiful shots of the surrounding L.A. area, and together with some wonderful shots of different venues where Sleep has previously played, such as the Sydney Opera House and the Cathedral of our Lady in Antwerp, as well as Richter’s endlessly calming music, the film comes across almost as a spiritual cousin to the Geoffrey Reggio and Philip Glass collaboration “Koyaanisqatsi.”

“Max Richter‘s Sleep” often captures the surrealism of dreams, especially characterized by the sharp digital photography interspersed with the archival footage of Richter and his family. However, the transition between analogue and digital material sometimes comes across as clumsy, especially as some of the archive images show a sprocket hole on the side that feels like it’s there just to say “this is from actual film stock.” We often have no idea who we’re talking to or where we are—we’re not told we’re in LA until a third of the way through the film by a concert announcer. I’d figured it out by noticing the Eastern Columbia building with its giant clock as seen in another classic set in the City of Angels, “Predator 2.”

On its face, “Max Richter’s Sleep” tells us to slow down. Of course, this is especially relevant given that COVID has kept many of us inside for months, but it’s an invitation to reappraise not only our connection to nature but also how we experience media. The challenge of putting on a concert like this, let alone creating the work in the first place, deserves a response greater than usually given, and while we’re being offered a hand to reassess things, we also should recognize the potential for something Max Richter seems to be able to do with his music: To transcend.

On MUBI today.