“Marley,” an ambitious and comprehensive film, does what is probably the best possible job of documenting an important life. Authorized by all the members of his scattered family and with rights to all of his music and a wealth of previously unseen film and video footage, it shows the growth of a legend. What’s interesting is that Marley seems not to have had a concrete goal for his career, other than to use music to bring people together. His instincts were good, and he followed them, and to an unusual degree, he found independence in a white-ruled music industry.

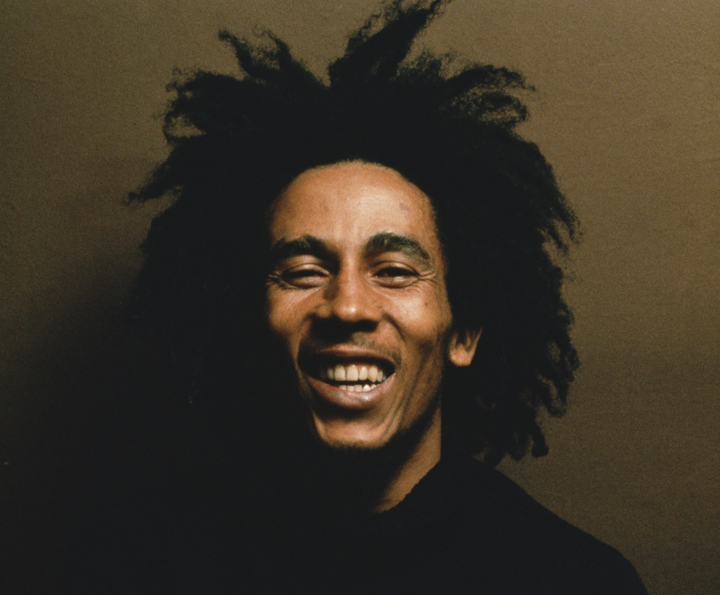

Marley was born in 1945 in the hamlet of Nine Mile in St. Ann Parish, Jamaica. Footage shows rude shacks, no electricity, barefoot children and a sense of community. His mother, Cedella, was 18. His father, Norval Sinclair Marley, was 60, a white captain in the Royal Marines. Norval married Cedella and provided cash support, but was all but unknown to the boy, who was bullied because of his mixed ancestry. It was his Rastafarian religion that helped him think above racial categories.

Using interviews from survivors of those years, “Marley” recalls how Bob began performing in grade school and recorded his first singles in 1962, with friends who were later to become part of his group, the Wailers. His mother got work as a hotel maid in Wilmington, Del., and musical history might have been different if he’d stayed in America. But after two visits, he returned home, formed the Wailers with Bunny Wailer and Peter Tosh, and began to create the kind of music that attracted local and then world audiences. Underlying it was the reggae beat that was the foundation of modern Caribbean music.

With Rita, his longtime wife and frequent singing partner, he had three children and adopted two of hers. The film reports he had 11 children in all. What is rather miraculous is that they all agreed to this film by Kevin Macdonald and granted rights to his music. Contemporary footage shows his crowds swelling so rapidly that he was soon doing stadium concerts and traveling with a rock-star entourage. Yet he remained concerned with Jamaica. He turned down offers to run for office, but returned to Jamaica at the height of a hard-fought election, triggering the film’s most powerful moment, when he brings two opposing politicians onstage to shake hands.

In 1977, Marley seems to have developed symptoms of malignant melanoma. He chose to overlook them, and a cancer that could have been treated in its early stages claimed him when he was only 36.

The passages depicting his final years are tremendously touching. He began to seek treatment when it was already probably too late and continued to tour, even though his fans noted with concern his weight loss and increasingly frail appearance. Finally, he went to a clinic in Switzerland, where the snow-covered mountains provided an alien landscape against which his death approached. The documentary features interviews with some of those who treated him and developed great affection; he had become in a sense a secular saint. He flew to warmer weather in Miami, where he died on May 11, 1981.

This film has no great revelations and will start no scandals — if indeed there are any. It’s a careful and respectful record of an important life, lived by a free spirit, whose “One Love” seems to be known in every land.