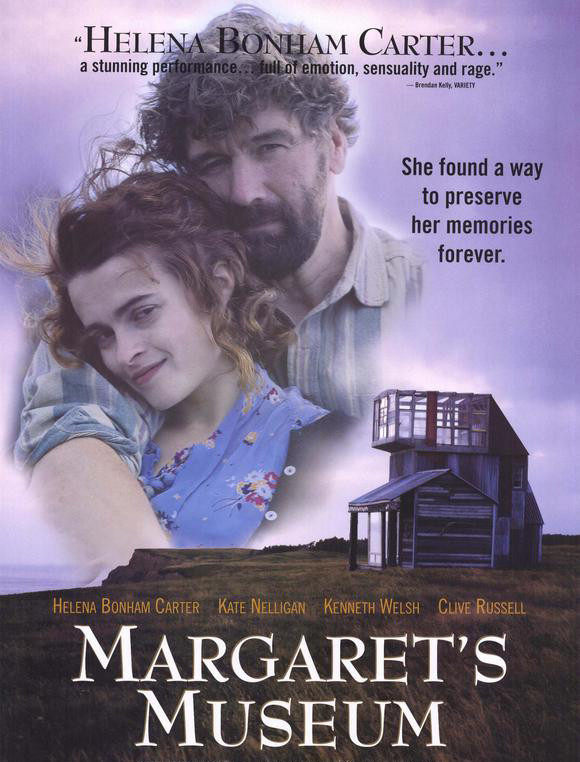

The opening shot of “Margaret’s Museum” looks like a painting by Andrew Wyeth, of a little clapboard cottage in a sea of grass on a cliffside. Two visitors drive up to the “museum,” and a moment later one runs from the house screaming. Then a title card takes us back “three years earlier.” As openings go, this one plays as if it belongs on another film. That it doesn’t gradually becomes clear. We are in the mining town of Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, in the late 1940s, where the coal pits take a terrible toll in life and limb–and where Margaret (Helena Bonham Carter) and her family live in half a house, because the earth subsided into a mine shaft beneath the other half.

Margaret scrubs floors at the hospital. One day a strapping fellow named Neil (Clive Russell) walks into the restaurant, half drunk, and begins to serenade her with big bagpipes. She scorns men, but likes this one, and brings him home to meet her bitter mother (Kate Nelligan), who has buried a husband and a son after pit disasters, and cares for a father whose lungs are so filled with dust that he needs to be regularly slammed on the back (“Don’t forget to thump your grandfather!”).

“Margaret’s Museum” is the story of the people who must make their living from the cold-hearted, cost-conscious mining company, but it isn’t like other films with similar themes (like “Sons and Lovers,” “The Molly Maguires” or “Matewan”). It’s quirkier and more eccentric, and has a thread of wry humor running through it. The dialogue, inspired by the short stories of Sheldon Currie, shows that Celtic wit has traveled well to the new land. (When Margaret encourages her younger brother to ask his girl to the Sunday dance, he replies, “They’re not supposed to dance on Sunday.” She tells him, “They’re not supposed to work. Dancing’s not work.” And he replies, “They’re Protestant, aren’t they? For them, it’s work.”) Most of the movie is the love story of Margaret and Neil. He towers above her slight frame and threatens to force them all out of the house with his drinking, his buddies and his songs. But he listens when she protests, and mends his ways. Soon he has built her the curious house near the sea, using parts scrounged around town. (The bedroom, with walls and a ceiling made from old windows, is going to be bloody cold in a Nova Scotia winter.) As Margaret’s mother, Nelligan is hard and dour, and can see no point in a life that snatches all of your loved ones away from you. “I’ll have five sons and three daughters,” Margaret tells her. “I can hear them in the bagpipe, screaming to be born.” Her mother’s predictions about the fates of these unborn infants are blood-chilling.

The margins of the movie are filled with colorful characters. With old grandfather, who coughs and writes his song requests on a note pad. With Uncle Angus (Kenneth Welsh), who dreams of sparing his nephew a life in the mines, and works double shifts in hopes that if he just once sees Toronto, he’ll see there is a different life waiting for him. With the pit manager, who orders his red-haired daughter (Andrea Morris) not to see Margaret’s brother (Craig Olejnik). The daughter and the brother perform their own marriage ceremony solemnly, before two candles in a root cellar.

The destination of the film may be guessed by some, but I will not reveal it, nor how it contributes to Margaret’s museum and its sign, “The Cost of Coal.” What is surprising about the film is not its ending, but how it gets there. Helena Bonham Carter might seem an unlikely candidate for this role (she took it in preference to the lead in “Breaking the Waves”) but she is just right–plucky, sexy, bemused, glorious in a scene where Neil sneaks her into the miners’ cleaning area and she takes the first hot shower of her life. Russell, as Neil, is sort of a rougher-hewn Liam Neeson, strong, gentle and poetic. And Nelligan is astounding in the way she allows her humanity to peek out from behind the mother’s harsh defenses. “Margaret’s Museum” is one of those small, nearly perfect movies that you know, seeing it, is absolutely one of a kind.