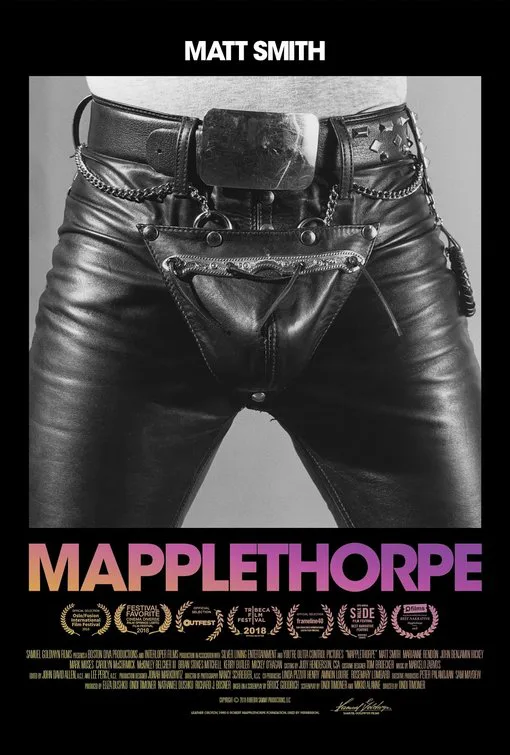

A phallic orchid; a man sticking his pinky finger in his erect penis; Donald Sutherland in a long coat—Robert Mapplethorpe’s black and white photography was provocative, raw, and unforgettable. But Ondi Timoner’s biopic, steered by a hollow performance from Matt Smith, is far removed from the artistic values within these images and the many more that he was known for. A stunningly drab take on the life and legacy of a photographer who merged pornography with grace, “Mapplethorpe” doesn’t have an artistic signature of its own, so much as a name it doesn’t live up to.

“Mapplethorpe” is defined by cliche biopic problems: a chronological approach and emphasis on facts that makes it a slow bore, as informative as the film might be for newcomers. It starts with him as a young man leaving the confines of the stuffy Pratt Institute to become a hustling artist in 1970s New York City. About five minutes into the movie he meets rising musician Patti Smith, who he famously had an artistic and romantic connection in the city’s artist-harboring Chelsea Hotel. Timoner’s presentation of their little world is underwhelming and lacks the tangible muck you can clearly see in footage from those days. An encounter with a magazine of naked men excites him as an artist, and as a sexual being.

The script, by Timoner and Mikko Alanne (based on a screenplay by Bruce Goodrich) shows the rise of Mapplethorpe the erotic photographer through the positive and negative relations he had with people in his orbit. After Smith falls out of the picture, he receives love and support from an art curator named Sam Wagstaff (John Benjamin Hickey), who opens up the former painter to the potential of photography, and helps him get two shows, one high-art and the other erotic, displaying the different sides of his artistry. His young brother Edward (Brandon Sklenar) goes from assistant to competitor, especially as Mapplethorpe becomes more consumed with working and making money. Other characters are brought into the mix, like his parents, different lovers, and even a priest (Brian Stokes Mitchell) from his childhood. As the script slowly drags Mapplethorpe to his sad end in the 1980s, the script becomes a list of different interactions, of which the dialogue does not make the saga any deeper.

The scenes become very pointed—here’s Mapplethorpe realizing how he feels when looking at this imagery of naked men, here’s his work displayed in two vastly different galleries, here’s a glimpse of him starting a ferocious sex session, here’s him telling Milton Moore to take his penis out of his polyester pants, and now here’s the real photograph that came of that. The touch-and-go storytelling helps the movie cram a lot of life into its 100-minute running time, but it imbues a passive quality, like a casual glance through a coffee table book. When the real photography is inserted—I was surprised that we did see some of the images within Mapplethorpe’s “X” collection—they’re often the best moments in any particular passage.

What the script gets best about Mapplethorpe is that electric sense of discovery within his work, how he seemed to learn what he liked as a sexual being and an artist at the same time. Sometimes that development is exciting—like when Mapplethorpe (who didn’t like photography earlier in his life) sees the painterly potential of the documented image—and sometimes it’s problematic, like when he started to fetishize black men later in his career. “Mapplethorpe” embraces the flaws within his artistry, and establishes its own sincerity.

Smith’s take on Mapplethorpe is reserved, which does not help when there are so many surface-level scenes that value exposition over subtext. His stony cheek bones are a strong fit for Mapplethorpe’s own chiseled mug, but his eyes have more intensity than Mapplethorpe does when you look back at old footage of the photographer, and Smith can’t create a rich interior life out of his interpretation. You get more of a sense of Mapplethorpe’s balanced perfectionism and impulsiveness from the dialogue than you do watching Smith’s Mapplethorpe behind a camera, or admiring his work in a gallery.

“Mapplethorpe” was shot on Kodak film, and that seems, in this very rare case, to work against this production’s texture and atmosphere. It lends a softness to images of sparse art studios, smoke-filled night clubs, or intimate moments in bed. Mapplethorpe’s world is dulled around the edges. It’s equally ironic and frustrating: a photographer biopic that will leave you wishing for the crispness of digital, something to honor those heavy darks and pure whites within Mapplethorpe’s work. Any time an actual photo is referenced, it’s an unintended recommendation to watch a documentary about Mapplethorpe instead.