“What it takes to sail around the world is, first of all, you have to be a bit crazy,” a voice tells us at the beginning of Alex Holmes’ moving documentary, “Maiden.” “You have to be different than the normal bloke.” Holmes’ subjects are certainly different than normal blokes in that they’re the first all-female competitors to enter a boat into the Whitbread Around the World Challenge. As with all firsts, the quest to be taken seriously is almost as insurmountable as the actual task at hand. And the Whitbread is no easy feat; it’s 33,000 nautical miles in total, most of which will be spent battling the Earth’s most plentiful and pissed off geographical resource, the ocean.

When we first see the boat that gives “Maiden” its title, she is both Webster’s definitions of scrappy: she’s in an advanced state of disrepair due to use, yet there’s a feistiness about her, an unwillingness to give up the ghost just yet. Though skipper Tracy Edwards chose Maiden for budgetary reasons, she and her crew set about to restore the ship to her former glory, then attempt to etch upon her an even greater victory. No woman had ever led a ship to win the Whitbread simply because no women skippers had been allowed to enter it. The best they could do was to serve as the vessel’s cook, a job Edwards held during the prior Whitbread. and even then, that idea was met with severe reservations and pushback.

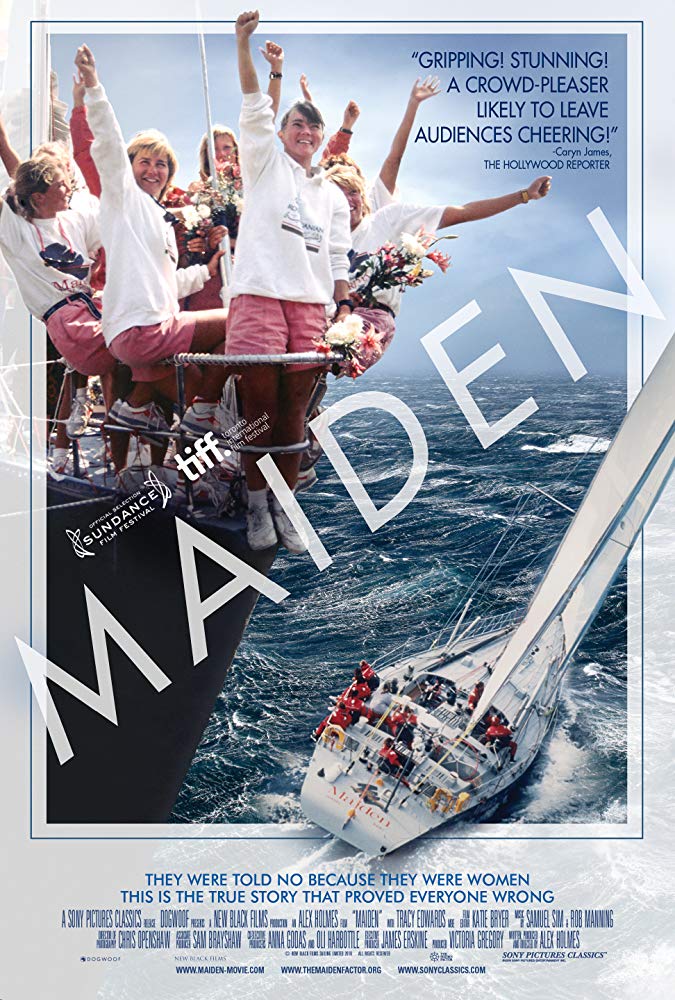

As with all things that are considered “boys’ clubs,” the general consensus is that there’s no place for a woman. Either she’s a visual distraction, an unskilled weak link or both. Such generalizations are rarely based on evidence as any opportunity to disprove them is dismissed rather than granted by the powers that be. Edwards has no problem finding a crew of women who share her passion and skillset for sailing, proving that there’s a market and an interest her male counterparts refuse to acknowledge. Edwards’ bigger problem is finding someone to sponsor her entry into the Whitbread. Either the companies she solicits think the idea of an all-female competitor is outright foolishness, or they love the idea yet don’t think there will be a return on their investment. Thanks to an unusual benefactor, the Maiden enters the nine month race in September, 1989.

Edwards is the first face we see in “Maiden,” and the first voice we hear. “The ocean is always trying to kill you,” she narrates over a series of terrifying waves that would give even the Beach Boys pause. “It doesn’t take a break.” Edwards then appears before us in promotional footage taken just before the race in 1989. She is focused on introducing herself as the skipper of the Maiden. She is dark-haired, with a youthful spark in her eye that reeks of the piss and vinegar supposedly reserved solely for men in their prime. Like far too many women, she’s repeatedly told to smile.

When the current incarnation of Edwards appears soon after, it’s a bit jarring not because she’s clearly older, but because that same youthful spark is present, its intensity unblemished by the passage of time. We see this spark in all the women who are interviewed in the present day—the back and forth editing constantly swaps boat footage shot by Edwards’ childhood friend and crewmate, Jo Gooding in 1989 with Holmes’ present-day talking heads, as if the two versions of the Maiden crew are conversing across time. This method is not only effective, it’s inspiring. When the elder Edwards chokes up at one point over a memory we’ve just witnessed, we can’t help but be pulled into the same emotions.

Edwards is as rich a character as one would find in a great seafaring novel, though as English class informed us, those stories were predominantly if not entirely male. Her parents instilled an independence in her, her Mum’s unconventional interests serving as the influential stereotype busters that would eventually underscore Edwards’ determination to enter the Whitbread. After her entrepreneur father died when she was 10, Edwards bore witness to the first major instance of the patriarchy’s far-reaching effect on female independence when her mother was forced out of running the family speaker business by male competitors who did not want to risk losing face by being bested by a woman.

This macho fear of losing to women bleeds directly into the Whitbread, with skippers Bruno Dubois and Skip Novak (the latter commanding a rival English boat) expressing their thoughts in 1989 about the Maiden’s lack of strength and cohesion. As with everyone else, we see those two, as well as journalists Bob Fisher and Barry Pickthall, in the present as well. While the skippers’ comments could be seen as trash-talking, the journalists’ pens were far more vicious, brutal and harmful to Edwards and her crew. Pickthall and Fisher shaped the public narrative and their mockery was relentless. “I wasn’t as misogynistic as the other guy,” says one of the two journalists, but they both seem to still be amused by the mean things they churned out.

While “Maiden” is far more concerned with depicting the Maiden crew’s strengths and accomplishments, it can’t help but see male ego issues every time it looks to the horizon. Edwards and her crew are asked completely different questions than their male counterparts. With Novak and Dubois, the reporters talk shop. With Edwards, Gooding and company, the questions are about makeup, fashion, gossip and the possibility of catfights. Even after the Maiden exceeds expectations, it’s written up as pure luck; only failure yields skill-based discussions. Thirty years on, little has changed in this regard.

I won’t tell you if the Maiden wins or loses simply because I didn’t know myself. I don’t think documentaries have spoilers, but the message of this film lies in the influence of the Maiden’s voyage, not the outcome of the race. It’s not lost on the filmmakers that the ocean, with its overarching command of death, is the only equal-opportunity proponent in the Whitbread. It’s a bitter irony that tempers the sweet taste of victory. “Maiden” excels as a suspenseful sports tale and a record of a historic first, but its biggest strength is in its warts-and-all character study of the Maiden crew. One can’t help but feel seen, moved and empowered once the credits roll.