“Mahogany” is a big, lush, messy soap opera, so ambivalent about its heroine that we can’t even be sure the ending’s supposed to be happy. And yet it’s unabashedly commercial and sure to be an enormous hit. Diana Ross inspires great fantasies even when they don’t add up to anything. The movie’s got rich costumes, romantic music, decadent playboys, socially redeeming values and a fable of rags to riches. Why should it have to make sense?

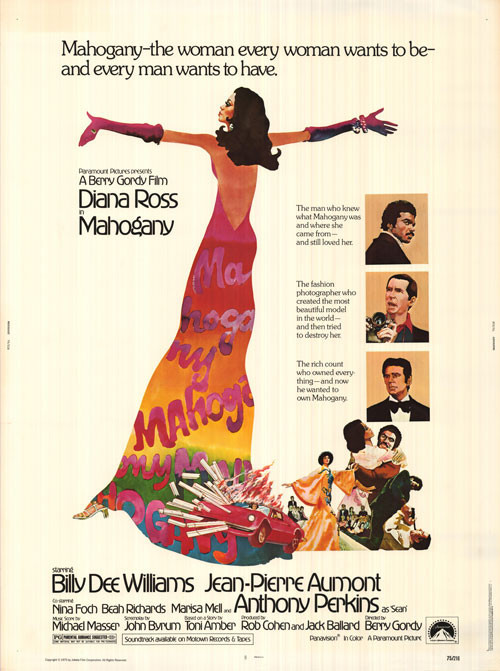

Miss Ross plays a black from Chicago’s South Side who works days as a secretary in a Loop department store, studies art in night school and dreams of becoming a top fashion designer. One day, she crosses paths with an activist politician (Billy Dee Williams, looking uncannily like Jesse Jackson), and it’s love at first sight. Well, almost. To play a trick, she pours milk into his portable bullhorn, and when he spills it all over himself, he thinks some hard hats did it, and there’s a fight. You see how tricky love is.

She bounces a check to get him out on bail, and then, in perhaps the most awkward of the movie’s many unlikely lines, explains: “I’m the one who turned your trumpet into a horn of plenty.” Nobody I know talks that way, but no matter. There follows an obligatory period during which they exchange ambitions. She’ll design dresses, he’ll run for alderman on a reform platform.

Things get considerably more complicated when Anthony Perkins enters the picture (things nearly always do). He’s a famous fashion photographer who wants to bring Diana Ross to Rome. She wants to model her own designs and, ambition being stronger than love, she skips the next campaign rally to fly Alitalia.

It’s here that the movie gets into considerably murky waters. Rome welcomes Mahogany, she’s a big success, but she refuses to sleep with the rich count (Jean-Pierre Aumont) who has befriended her, and when she agrees to sleep with Anthony Perkins, it turns out (as it nearly always does) that he’s impotent. He’s also paranoid and psychotic (as he nearly always is), and we realize that Perkins is just supplying his standard performance, quirks and all.

Billy Dee Williams flies to Rome on vacation, and he and Perkins have a confrontation in a particularly effective scene about a gun. Williams flies back to Chicago, and Miss Ross gives herself over to a life of dissolution, dramatically represented by Scotch on the rocks.

By now, we realize we’ve walked into an unholy alliance between daytime soap opera and Jacqueline Susann, but the movie doggedly marches through its remaining cliches. Just before Billy Dee left for Chicago, he told Mahogany: “Success means nothing unless you have someone to share it with!” At the time, I had a presentiment that we’d hear those words again and, sure enough, we do. They echo ominously on the sound track at Mahogany’s moment of greatest triumph, and so she goes back to Chicago. A lot of money is spent on air fare in this movie.

Meanwhile, we’re getting confused about the meaning of it all, because “Mahogany” has two themes that never are resolved. The first, forcibly articulated by Miss Ross, is that her responsibility is to herself, her talent and her career. The second, just as convincingly articulated by Williams, is that her place is in Chicago with the brothers and sisters, helping to build the community, instead of in Rome with a gaggle of omnisexual perverts.

Unfortunately, those seem to be the only two choices. Neither character seems to consider it possible for her to be a successful fashion designer in Chicago, so her “good” choiceis to subjugate herself to Williams’ political career to stand by her man. “Mahogany” would certainly offer some awfully uncomfortable moments for any black feminists who happen to be in the audience.