If the Lord moves in mysterious ways, his wonders to unfold, rarely can he have worked more mysteriously than in the case of Sam Childers, a Pennsylvania ex-con, drug addict and thief who was born again, and since 1998, has been leading a crusade on behalf of the wretched orphans of South Sudan. “Machine Gun Preacher” is a combination of uplift and gritty violence, and the parts don’t fit.

We hear about Sudan all the time. There is little ambiguity there. In Africa, a warlord named Joseph Kony runs something called the Lord’s Resistance Army that has murdered hundreds of thousands, burned villages, and kidnapped some 50,000 children, forcing the boys to become soldiers and making the girls sex slaves. He is an evil man, and while we’re occupied in trying to bomb Gaddafi, we might profitably drop a few on him.

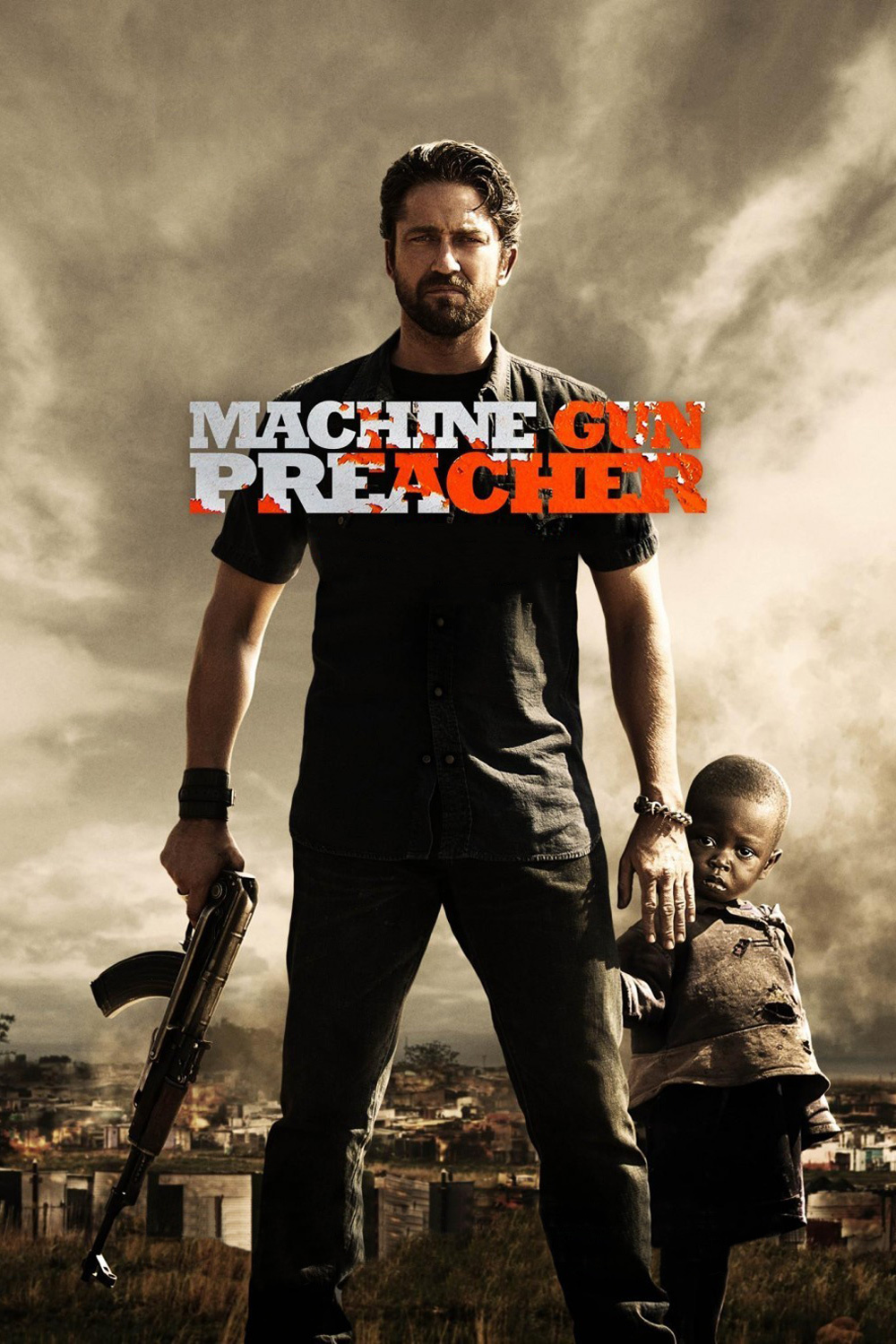

In this film, which begins in Pennsylvania, we meet Childers (Gerard Butler), who with his buddy Donnie (the always effective Michael Shannon), drinks, drugs, raises hell and makes things hard on his wife, Lynn (Michelle Monaghan), and daughter. While he was in the pen, Lynn found God. One Sunday morning, after a bloody night of violence, Sam allows himself to be dragged along to a church service, where he confesses himself to be a sinner and then undergoes a baptism of full immersion.

It takes. One day, he hears a sermon from a missionary from Sudan, describing the plight of the orphans. Sam knows the construction business and informs his astonished wife that he feels called to go to Africa and see what he can do to help. There is a lot. Faced by the specter of overwhelming suffering, he builds an orphanage, raises money from home to help out and becomes a driven man.

Eventually, so dire is the situation, Childers returns to the instincts of his violent past and finds himself fighting against the Lord’s Resistance Army as a commander in the Sudan People’s Liberation Army. Thus the movie’s title. Well, Childers isn’t the first to go to war in the name of the Lord.

The enigma at the heart of the film is the quality of his actual spirituality. He’s born again, yes, but he seems otherwise relatively unchanged. He still gives full vent to his drives and instincts, and still, if you get down to it, gives himself license to break the laws, such as they are, in Sudan. I learn from an article by Brett Keller in Foreign Policy magazine that as Childers was fund-raising in the United States, the Sudan People’s Liberation Army issued a statement saying, “The SPLA does not know Sam Childers. We are appealing to those concerned to take legal measures against him for misusing the name of an organization which is not associated with him.”

There’s more, about “his narcissistic model of armed humanitarianism.” That’s what bothered me. He seems fueled more by anger and ego than spirituality and essentially abandons his family to play with his guns. It’s intriguing, however, how well Butler enlists our sympathy for the character.

The film has been directed by Marc Forster (“Monster's Ball“), from a screenplay by Jason Keller that’s efficient scene by scene, but seems uncertain where it’s going or what it’s saying. Since much of the killing in northern Uganda and South Sudan is driven by sectarian and tribal prejudice, I’m not sure that shooting back is a solution — particularly when it’s done by a self-anointed white savior from the West.

The sight of Sam Childers with his machine gun and his ammo belt reminds me of the night at O’Rourke’s when a guy flashed a handgun for my friend McHugh.

“Why are you sportin’ that pistol?” he asked.

“John,” the guy said, “I live in a dangerous neighborhood.”

McHugh replied: “It would be safer if you moved.”