How is it possible to be in love with a man for 20 years, and believe all the time that he is a woman? The French, who consider themselves expert on matters sexual, were baffled by that question during the celebrated trial of Rene Gallimard, an attache at the French embassy in Peking – who, it was revealed, conducted an affair for years with a Peking Opera star who was both a man and a spy. Did Gallimard never see his lover unclothed? Did his hand never once stray. . .

But there is no answer to such questions, except for the one that David Henry Hwang suggested in “M. Butterfly,” his stage success that has now been filmed by David Cronenberg. The answer is that Rene Gallimard did not know because he did not want to know. That for 20 years he was in love with an ideal woman of his dreams, and permitted no reality to intervene.

This explanation sounds like romantic idealism, but Hwang suggests, more darkly, that Gallimard also was blinded by his white Western fantasies about a submissive Asian woman. He so desperately required this person to be the butterfly of his dreams that he was simply blind to all other evidence. His self-deception sets the stage for the play’s drama, in which the Asian butterfly is victorious, for once, over the visiting European.

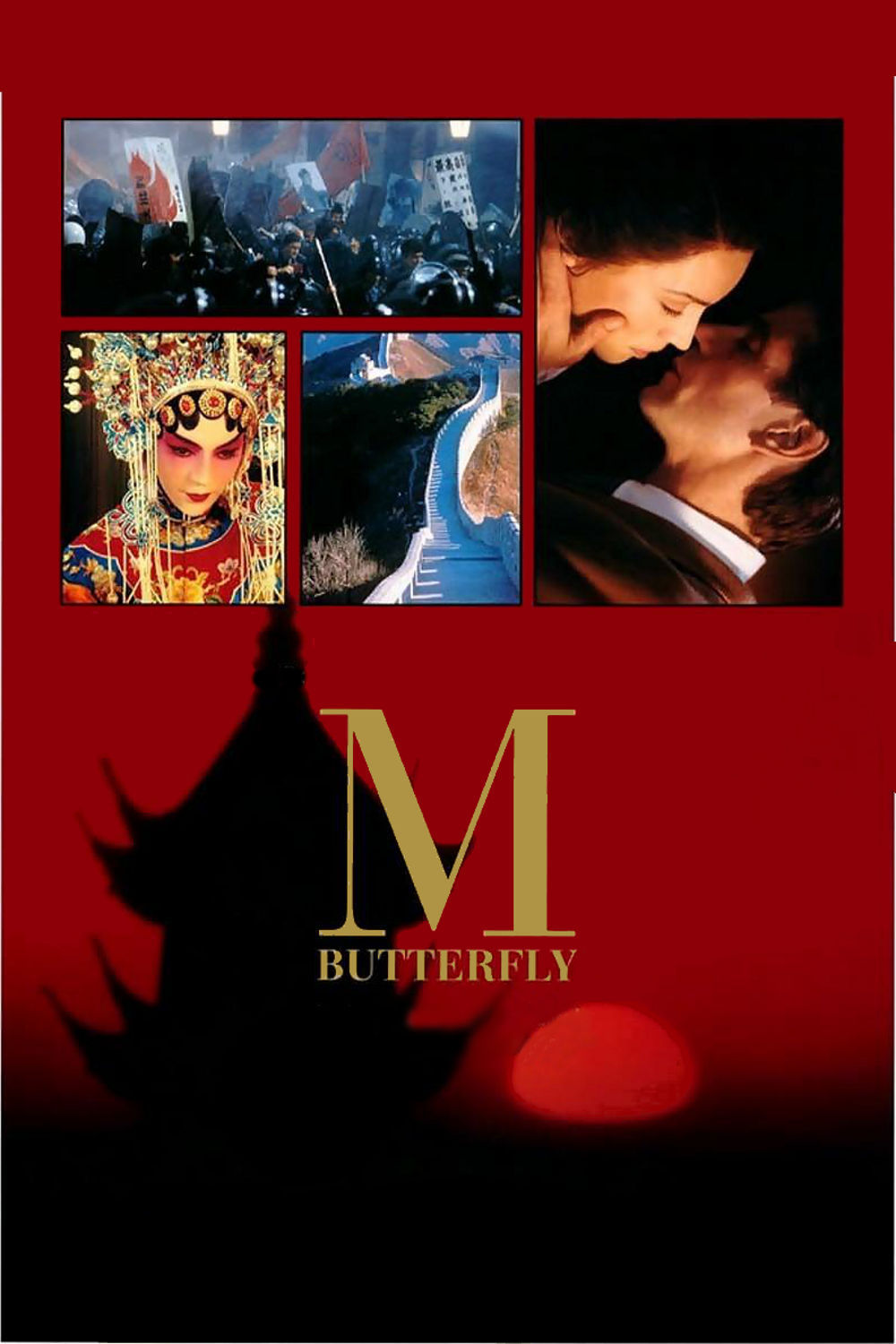

On the stage, the audience could be blind, as well. In the screen version, it is impossible to create the illusion. John Lone, as Song Liling, the transvestite opera star, does not make a convincing female, and is perhaps not intended to. Unlike “The Crying Game,” which created a successful deception, “M. Butterfly” keeps the secret, not from the audience, but only from Gallimard. There is even dialogue in which Song Liling observes that in Peking Opera, all women are traditionally played by men. (Another movie opening this fall, “Farewell My Concubine,” features a Peking opera star who is quite convincing as a woman.) Gallimard is played by Jeremy Irons, the screen’s poet of tortured sexuality, and no one else could have done a better job of suggesting the inverted obsession that leads him to fixate on a “woman” who keeps him always at arm’s length. Irons bases his performance on the understanding that erotic impulses are always completely humorless to those who hold them, even though they might seem hilarious to the observer. “Are you my Butterfly?” he asks at a moment of great pain, and his agony prevents us from smiling. The answer he receives, of course, is “yes.” Song is his butterfly, all right; he is simply not anything else Gallimard thinks he is. (Old proverb: Be careful what you ask for because you may get it.) The movie is set mostly in Peking, in a world that the visiting diplomat finds even more exotic and mysterious than perhaps he should. Entranced by his first sight of Song Liling, during a performance at a diplomatic function, he falls immediately in love, forgets his wife and his responsibilities, and embarks on a mad passion that leads to scenes in which Song, remaining fully clothed, leads Gallimard into an erotic deception the movie wisely leaves to our imagination. There is a point at which Song fears the deception will be unmasked (not much of a danger, given Gallimard’s wilful blindness) and produces a trump card: An announcement of pregnancy, followed by a confinement in the country and the triumphant production of an Eurasian baby.

All of this is interesting, in its way, and yet the film of “M. Butterfly” does not take hold the way the stage play did. Perhaps the camera is too cruelly realistic, reminding us at wrong moments that Song Liling seems to have 5 o’clock shadow. Perhaps it is Lone’s voice, so low and monotonous. Perhaps it is two closing scenes, one in a police paddy wagon, one in a prison, that fly so recklessly in the face of plausibility that we’re distracted.

Would the Paris police allow Gallimard and Song Liling alone together in a paddy wagon? Would prisoners be polite and attentive at Gallimard’s strange theatrical performance behind bars? The central question of the Gallimard case – “Why didn’t he realize that this was a man?” – was somehow sidestepped in Hwang’s stage play, freeing it to move on to his other issues. But it was never answered in the courtroom, and now it is not answered in the movie, either. And without that answer, there is no story.