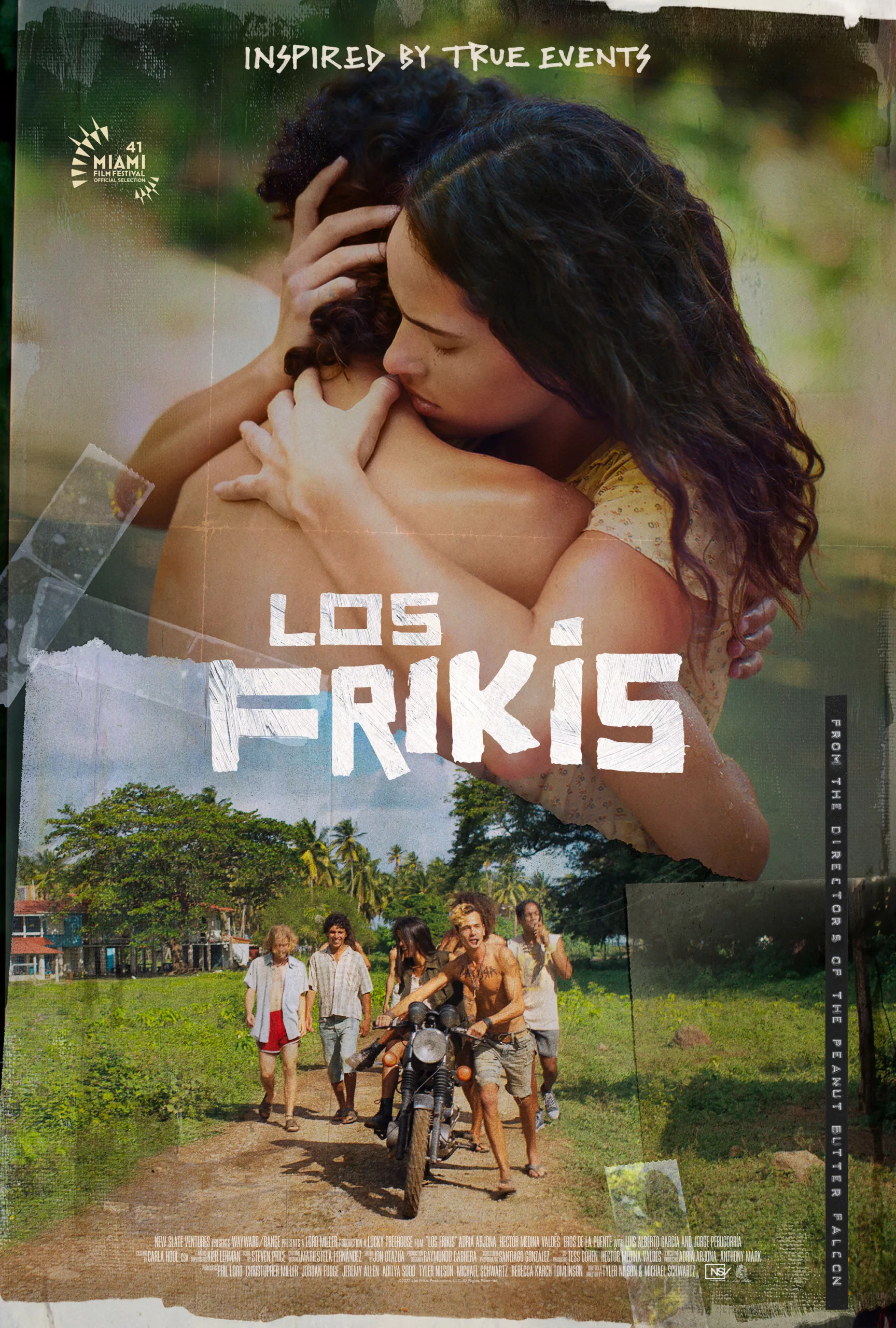

Stories of Cuba’s Special Period still loom large in the memories of many Cubans on and outside of the island. The collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s ushered in a period of austerity so severe that it triggered another large wave of migration out of the country—the largest since the Mariel boatlift a decade earlier. For those that remained, desperation became rampant as shelves were as empty as the population’s stomachs. Tyler Nilson and Michael Schwartz’s “Los Frikis” begins during these dire times, following two brothers, heavy metal frontman Paco (Héctor Medina) and kindhearted Gustavo (Eros de la Puente), as they struggle to survive with their uncle Mateo (Luis Alberto García), who only begrudgingly look after them after his brother’s death.

Paco is a self-identified Friki, a hardcore rock fan, who not only listens to the “music of the enemy” but plays his own angry songs with a band and dresses in tight jeans, torn shirts, and a mohawk, earning both police harassment and taunts from his neighbors. After falling out with Mateo for the last time, Paco devises a plan to inject himself with HIV so that the government quarantines him and provides him with what they wouldn’t on the outside: food and shelter. Gustavo, afraid of losing his sibling, fakes catching HIV to reunite with his brother and finds a paradise of misfits at the rural sanitorium, but only if he can keep his true status a secret.

“Los Frikis” is based on a true story of a movement within Cuba’s metal scene, where both prominent figures and fans injected themselves with HIV to survive the Special Period. Unfortunately, it led to even more infections and deaths, as the virus was still widely misunderstood. Not all Frikis followed suit, but as one former member recalled in a Vice documentary, the sanitorium he went to was almost all exclusively Frikis when he arrived. My introduction to their story came from the Radio Ambulante’s episode “When Havana was Friki” which explained the term and gave a sense of the community that formed around listening to illegal U.S. radio waves, swapping bootleg tapes of banned artists and the Spanish language music scene that percolated in clandestine house shows and the few venues that would host these strange looking kids. Cuba’s policy on the HIV epidemic at the time was to quarantine people who tested positive, taking them away from their loved ones and communities to a sanitorium, isolating them away from the rest of the population for years, a storyline also brought to the big screen in Pavel Giroud’s stellar drama “El Acompañante.”

Nilson and Schwartz’s film, which they wrote and directed, grounds the story of “Los Frikis” with plenty of historical detail to immerse the audience in this turbulent era. Sometimes, it’s helpful context, especially for those who may not know what Cuba’s Special Period meant. Still, other times, it’s distracting, like the intrusion of an English-language U.S. news broadcast recounting an experimental treatment a Cuban doctor explained just moments before. Other times, it’s glaringly apparent how much the filmmakers wanted to contrast the dreary street life during the Special Period against the glowing rural paradise where Paco, his Friki friends, and Gustavo played music, ate ice cream, and enjoyed their own bed, all luxuries they didn’t have back in the city. During these scenes, Nilson, Schwartz, and cinematographer Santiago Gonzalez film the Dominican Republic standing in for Cuba in a golden light, complete with a breathtaking vista, humble cabins near an idyllic stream, lush green mountains, and a wild horse Gustavo looks after that becomes a spiritual equivalent to his brother’s untamed spirit. Composer Steven Price’s music swells at almost every opportunity to heighten emotions, smothering the narrative with extra feelings.

Gustavo does not follow in the Friki footsteps of his brother and functions more as an outsider looking in like an audience surrogate. At the start of the film, he’s so passive, even his uncle commends him for being more like his quiet mother than his reckless father, who Paco resembles. In his feature film debut, De la Puente is sometimes upstaged by Medina’s antics and unbridled performance as Paco. He’s the live wire setting the film in motion, and the story changes pace almost as soon as the camera looks away from his aggressive stares and lanky but stubborn shoulders. His presence is lacking in the film’s second half when the story shifts from the brothers to the steamy affair that Gustavo begins with the sanitarium’s caretaker, Maria (Adria Arjona). I had higher hopes for Maria’s role, especially since Arjona was so charming in “Hit Man,” that I was deeply disappointed to see her relegated to mere love interest before too long. Although their appearances are brief, it was a thrill to see Cuban film legends García (“The Last Supper”) and Jorge Perugorría (“Strawberry and Chocolate”) as a doctor in the cast, who were just a few of the many Cuban artists both in front of and behind the camera involved with the production, including the film’s Cuban American producer Phil Lord.

“Los Frikis” is a complicated movie with good intentions and the goal of sharing underreported stories from the island. I want that too, but I found “Los Frikis” too saccharine given its somber topic. Perhaps its harder-edged critiques were softened for international audiences, but I would have preferred the film to more thoroughly wrestle with the emotional, political, and social complexities at its center. I didn’t need a wall of upbeat music on the way to the sanitorium or melodramatic scenes of defiance to force my feelings. I only had to think of what my family went through—what many of them are going through today amid another economic downturn on the island—to empathize with these characters. The sweetness that made Nilson and Schwartz’s “The Peanut Butter Falcon” a heartwarming film about friendship feels out-of-place on “Los Frikis.” There is a desire to make this an uplifting story, and given its “A Star is Born” ending, it feels like a tonal mismatch. There are many more Cuban stories to tell in and out of the island; let us exist outside of cookie cutter endings.