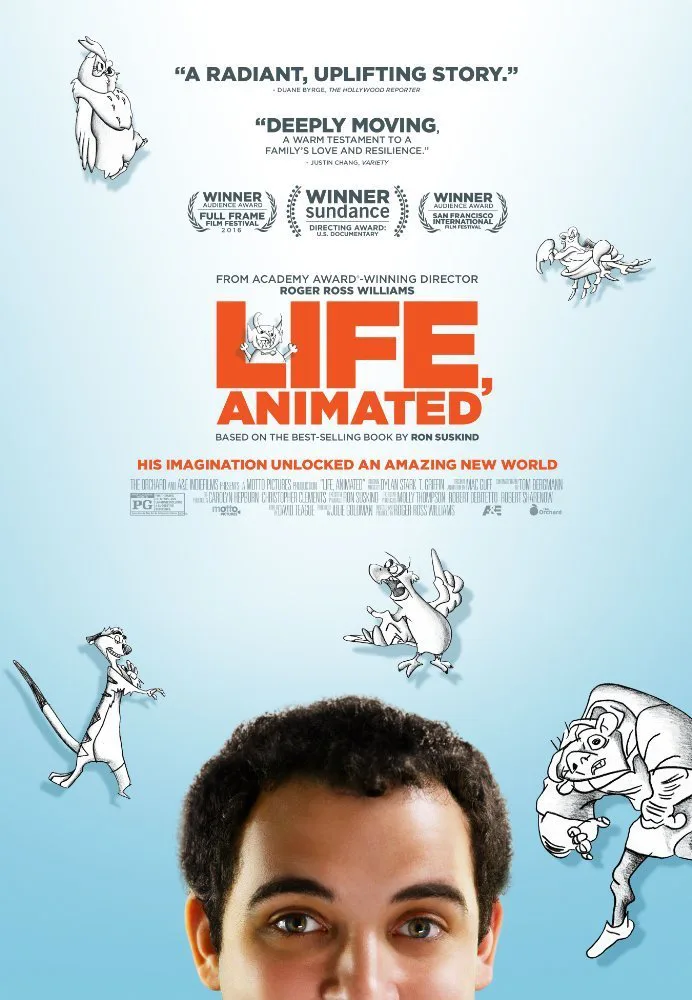

When Owen Suskind was three years old, his motor and language skills deteriorated, seemingly overnight. He retreated from the world. His parents took him to specialists, hoping there would be some way to “fix” Owen. It was the 1990s, and so autism, or the concept of the “spectrum” had not moved into common currency yet. When Owen was diagnosed with autism, his parents were devastated. But finally, light from the caves of Owen’s mind: his family discovered that Disney’s animated movies, beloved by Owen, allowed Owen to access his emotions and put those emotions into words. It was a huge breakthrough. Owen Suskind is now 23 years old, and his journey is the subject of Roger Ross Williams’ heart-rending documentary “Life, Animated.” Based on the book of the same name written by Owen’s father Ron Suskind (a Pulitzer-Prize winning journalist), the documentary shows Owen’s childhood (through home-movie footage) and flips forward to his current situation where he is about to leave his group home and get his own apartment for the first time.

Ron Suskind wrote in a 2014 article in The New York Times, “We were never big fans of plopping our kids in front of Disney videos, but now the question seemed more urgent: Is this good for him? [The doctors] shrug. Is he relaxed? Yes. Does it seem joyful? Definitely. Keep it limited, they say. But if it does all that for him, there’s no reason to stop it.” Disney movies helped Owen relate to whatever he was going through in his life, and it helped his parents and his older brother communicate.

Owen is first shown as an adult, wandering along a sidewalk by himself, speaking what sounds like gibberish. Over the course of the film it becomes clear what he is doing: using funny voices from characters in Disney movies, dialogue from favorites like “Peter Pan,” “Aladdin,” “The Lion King,” “The Little Mermaid.” Unlike his three-year-old self, though, he now can speak words other than Disney dialogue (he also taught himself to read from the end-credits of Disney films). He uses slightly formal language, asking his mother at one point after a personal disappointment, “Why is the world so full of pain and tragedy?” He spends his time at his group home learning from therapists how to deal with everyday situations, in preparation for his exit from the safe environment. Owen started a Disney Club at his group home, where the residents gather, watch a film and then talk about it afterwards. Owen, leading the discussion, asks the group, “What is Mustafa teaching Simba?” Owen is a leader (he is now a spokesman-advocate for people who are autistic).

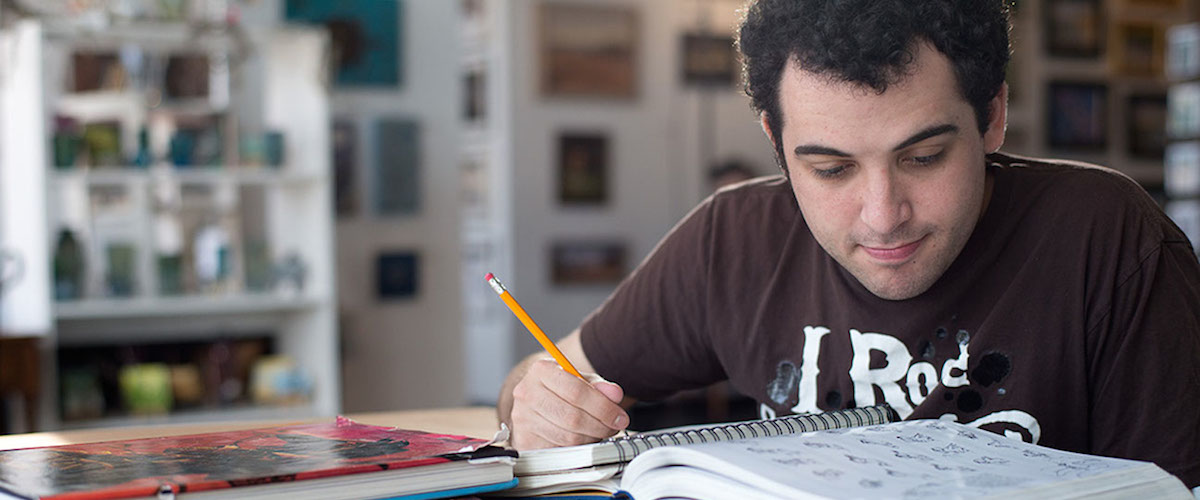

Owen’s childhood is presented in the film by his parents, Ron and Cornelia, and his older brother Walt, sharing memories of what happened, how they felt. These backstory sequences are accompanied by home movie footage as well as evocative animation, created by Mathieu Betard, Olivier Lescot, Philippe Sonrier. The animation grows in complexity as Owen starts to join the world. At first, for example, there’s a small black-and-white boy shown standing at the end of a long dark hallway, no way out. Later, the animation goes to fantastical Technicolor, as Owen accesses his own creativity. Owen was bullied in school, and he found comfort in drawing various Disney characters. Ron Suskind, looking at the piles of artwork by his son, realized at one point that Owen only drew the “sidekicks,” never the heroes. Owen declares: “I am the protector of sidekicks. No sidekicks get left behind.”

Throughout, the adult Owen is shown dealing with the stresses of his life by watching Disney films. In the first night in his new apartment, he lies in bed watching “Bambi,” in particular the wrenching scene where Bambi’s mother is killed. It’s how Owen feels: He’s lonely for his mother. The Disney movie says, “We know. This is tough. Bambi got through it and so will you.” Disney footage abounds in “Life, Animated,” and these familiar images resonate in a totally new way, as seen through Owen’s eyes. They are stories about adversity, pain, looking for belonging, sparks of joy and togetherness, being lost and then being found. The first thing Owen does in his new apartment is unpack his boxes and boxes of Disney movie VHS tapes.

Life is not all sunshine and roses. Owen’s anxiety is often acute and debilitating. Ron and Cornelia still tear up when they talk about Owen “vanishing” (Ron’s word) at age three. Owen’s older brother Walt, older and wiser than his 26 years, speaks openly about his fear of what will happen to Owen later in life, what will happen when their parents die. It will be Walt’s responsibility to make sure that Owen is okay, and the thought is overwhelming. Owen has a girlfriend named Emily, and there’s an endearing scene where Walt and Owen play miniature golf, and Walt tries to give his brother the “birds and bees” talk, to prepare him for what a relationship might entail. Walt gives it a shot, saying, hoping Owen will fill in the blank, “When people kiss, they don’t just kiss with their lips. They kiss with their … ” Owen guesses, “Feelings?” (It’s actually a pretty good answer.)

“Life, Animated” is powerful and emotional, without being manipulative. It is deeply inspiring, without trying to be. It is honest about Owen’s struggles, and the struggles of his family. It does not soft-pedal the difficulties. It shows the group-effort of the family to set Owen up in life, get him the help he needs, and validate who he is (as opposed to who they wish he could be, as opposed to yearning for who he was “before”). “Life, Animated” is also (perhaps the most moving part of all) a testament to the power of art and a shining example of what it can do.