Baltimore, 1954. Integration is the law of the land, and none too soon for Ben Kurtzman and his best pals, who are freshmen in high school. They regard the sign outside a municipal swimming pool: “No Jews, dogs or colored.” Dogs they understand. They ask themselves why Jews are listed first and decide it’s because “you never see any colored at the beach, so it must be directed mainly at Jews.” Not deep analytical thinking, but they are distracted by the girls on the other side of the chain-link fence, their plump bits displayed in frilly bathing suits. This will be a year of discovery for Ben, and by the time it is over, he will understand more about Negroes, Jews, segregation and himself.

Ben (Ben Foster) has been raised in a neighborhood so Jewish that when he is offered the gentile staff of life, Wonder Bread, he looks at it in amazement: “I’ve never seen raw bread before. We toast it.” At school, he is interested in Sylvia (Rebekah Johnson), a black girl whose presence in their classroom is an aftershock from the earthquake of Brown vs. the Board of Education. The morning begins with the recitation of the 23rd Psalm, and Ben notices that Sylvia closes her eyes and really seems to be praying, and that touches him.

“Liberty Heights” understands in that scene an important element of adolescent romance: It can be based more on idealism than lust. Yes, in locker rooms teenage boys make crude remarks about girls. But in their hearts the girl they idealize is perfect, blessed, the embodiment of their most fervent desire (which is to be noticed and loved by the girl they have chosen for sainthood). Ben thinks Sylvia is “pretty attractive,” he tells his mother, who is stopped in her tracks that her son would say this of a Negro girl: “Just kill me now!” Ben backtracks: “I said she was attractive. That doesn’t mean that I’m necessarily attracted to her.” But he is. Yet “Liberty Heights” is not so much about romance, interracial or otherwise, as about coming of age and finding your own two feet in the world. Ben’s older brother Van (Adrien Brody) is also in love, with a gentile girl he has seen at a party. She is Dubbie (Carolyn Murphy), a blond Cinderella to his eyes, and he spends much energy trying to get an introduction through a WASP friend. Will either Van or Ben end up marrying a girl who is not Jewish? Not the point. The point is that the residential and social segregation which raised walls between all of Baltimore’s communities is coming to an end.

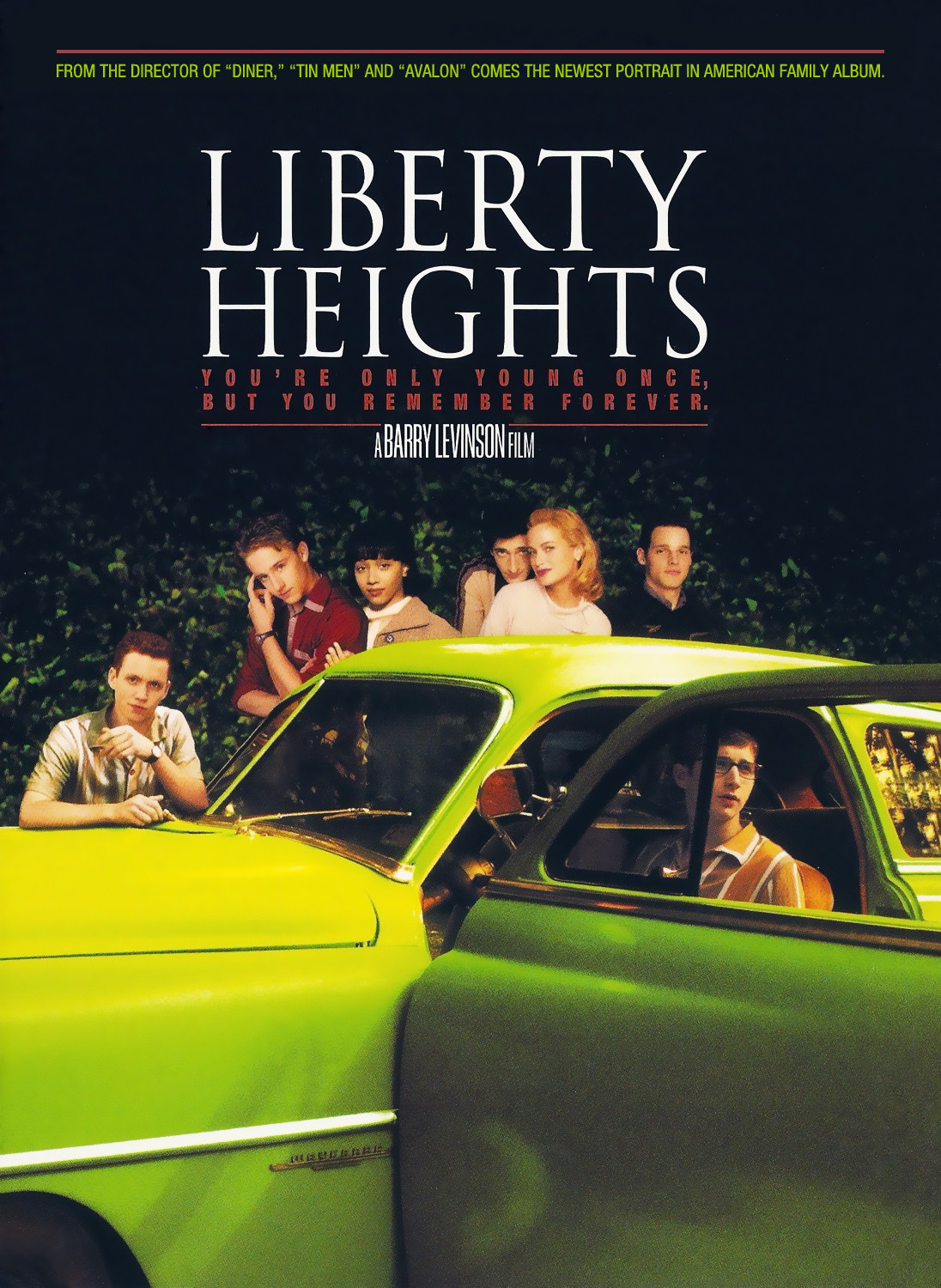

“Liberty Heights” is the fourth of Barry Levinson’s films set in his hometown of Baltimore (the others are “Diner,” “Tin Men” and “Avalon“). He makes big Hollywood films (“Rain Man,” “Disclosure,” “Good Morning, Vietnam“) and then he makes these more personal Baltimore pieces, and you can feel the love and nostalgia in them.

I assume the character of Ben is based on Levinson himself, or someone he knew very well. The best thing about Ben is that he doesn’t know then what we all know now. The movie doesn’t give itself the benefit of hindsight: It remembers the racial divides of 45 years ago, but it also remembers the innocence of a time when a high school freshmen would probably not have smoked, would know nothing of drugs, would have little sexual experience, would be big-eyed with wonder at the unfolding world.

For me, the truest scene is the one where Ben goes over to Sylvia’s house and they listen to Redd Foxx records (probably her father’s). In the time just before rock ‘n’ roll broke loose, it was not so much music as comedy albums that spoke to young teenagers of freedom, risk and daring. That scene ends with Sylvia’s father, a doctor, coming home early, and Ben hiding in the closet. The doctor’s conversation with the closed closet door is funny and terrifying at the same time.

We meet Ben’s parents Nate and Ada (Joe Mantegna and Bebe Neuwirth), and the rest of his family. We see family dinners interrupted by mysterious phone calls. “What does Dad do?” asks one of the kids. Mantegna runs a burlesque house and a numbers game, yet is a good provider and faithful family man, and scrupulously honest–so honest that he risks losing everything when a lowlife named Little Melvin (Orlando Jones) wins a $100,000 lottery that Nate unwisely tacked on top of the numbers payoff in the expectation that no one would ever get lucky.

One of the film’s best sequences involves a sort of date that Sylvia and Ben go on, separately. A young rhythm and blues singer named James Brown is playing at the Royal, and both kids want to see him. They dare not go as a couple. So they both go with their best friends, sitting a few rows apart, loving the music, happy to be in the same balcony together.

The film leads to a final scene which is one of those perfect public displays of poetic justice. I didn’t quite believe it, but I’m glad it was there, anyway, especially in the way it plays against the parents without making them the bad guys.

“Liberty Heights” has some weaknesses. I thought that the Little Melvin character was too broadly drawn, and I thought that the whole subplot about how he tries to collect his winnings could not unfold as it does here. (The Mantegna character comes across not merely as a nice guy, but positively Gandhi-like.) But those flaws are not fatal, and the movie emerges as an accurate memory of that time when the American melting pot, splendid as a theory, became a reality.