Set among the Irish working people of Liverpool in the 1930s, Stephen Frears’ “Liam” shows us a family where the children are terrified of sin and their parents of poverty. The first is more easily combatted than the second; in two crucial personal transformations, the 7-year-old boy makes his first confession and communion, and his father joins the fascist brownshirts of Oswald Mosley. Both are obsessed with blame; the father blames the Jews for his unemployment and poverty, and his son blames–himself.

This is, says Charles Taylor of Salon, the movie that “Angela's Ashes” might have been, and he is correct: It is harder-edged, more unsparing, and when the father tells his wife, “we’re skint,” he is not making an announcement but accepting a doom. Broke and unemployed, he is expected to outfit little Liam (Anthony Burrows) in a nice new suit from the tailor shop for his first communion. The way he sees it, to pay the Jewish tailor, he has to get funds from the Jewish pawnbroker, and when, on First Communion Sunday, the priest in his pulpit compliments the children on how well they are dressed, Dad (Ian Hart) stands up furious in his pew to cry out in the church: “Do you know how much it costs to dress the children, Father?” He then goes on to blame the Jews, although he might better blame the church itself, for not welcoming the children of the poor in whatever clothes they have.

Times change. I was reminded of Ken Loach’s “Raining Stones” (1994), in which it is the unemployed father who is determined his girl have a nice communion dress, and the priest who tries to talk him out of it. That priest even goes on to make a tricky moral judgment, which seems to owe more to situational ethics than to church doctrine; he is that rarity in the movies, a clergyman who is good, flexible and sympathetic. The priest in “Liam” seems straight from the pages of James Joyce, terrifying the children with visions of hell and informing them that their sins drive the nails deeper into the hands of Christ, which may be more than you can handle when you are 7 years old.

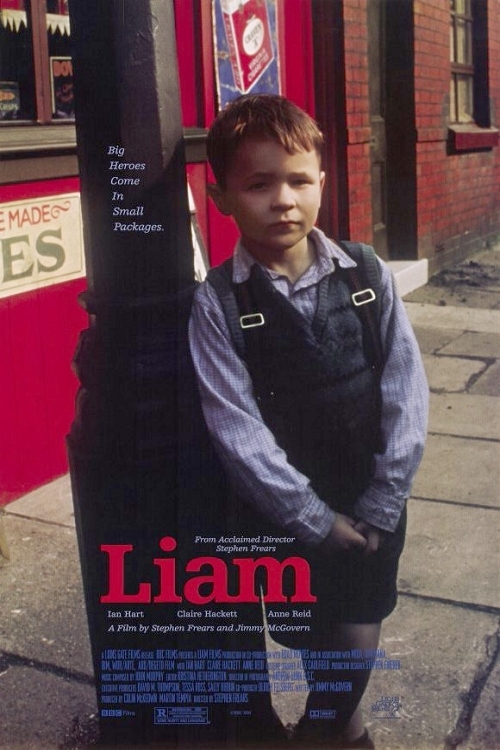

The film is built on strong performances, but two stand out. Little Anthony Burrows, short, stout and always in earnest as Liam, has a stutter which makes it almost impossible for him to get the words out. Sometimes this works to his advantage; He takes a suit to the pawnshop instructed to get “seven and a tenner” but seizes up and gets nine and a tenner when another customer appeals to the good heart of the pawnbroker. During Liam’s first confession he literally cannot say a word until he hits upon a sudden inspiration that releases the flow.

What he wants to confess is that his sins have caused his mother to grow hair upon her body. This he knows from having accidentally seen her in her bath, and comparing her body with the hairless perfection of the art reproductions so thrillingly studied in secret by the boys at school. The priest, who is not a bad man but simply clueless about children, is able to relieve him of this great burden.

The other performance is by Ian Hart, a British actor you may not even recognize, although he has given a series of brilliant, self-effacing performances. He plays the kind of man who cannot bear the pain of seeming insufficient and must blame somebody. We see him lining up with the other unemployed men outside a factory, hoping to be chosen by the foreman. We see him buying a pint of Guinness for the foreman as a bribe–and still being passed over, and spitting in the man’s face. And we see how for him the attraction of fascism and anti-Semitism is that it removes the guilt from his shoulders; it is his form of absolution, and when he puts on his fascist shirt and marches out to join a rally, you get a vision of hate groups as clusters of the weak, clinging together to seek in the mob qualities they lack in themselves.

Two children have work: Con (David Hart), the older brother, brings home is paycheck but is at war with his father, and Teresa (Megan Burns) is a housemaid for a wealthy Jewish family, and gets bribes from the wife for keeping quiet about an affair she is having. There is a Jewish daughter, about Teresa’s age, who wants to be friendly across the class divide. When Teresa is given some of her dresses, it’s no problem that they’re hand-me-down; what breaks Teresa’s heart is when she is asked by her mother to select one so the others can be pawned.

Some will find Dad’s last big act in the movie too melodramatic. I think it follows from a certain logic, and leads to the very last shot, which is heartbreaking in its tenderness. The film as a whole suggests that Catholicism (in those days in that society) came down more heavily upon children than some of them could bear, and that children thus diminished in self-esteem might grow up to seek it in unsavory places. It makes a connection, in some cases, between extreme guilt and low self-esteem in childhood and an adult attraction to the buck-passing solutions of racism, fascism, and even, as Dad’s final big scene makes perfectly clear, terrorism.