Two American photographers enter Adolf Hitler’s apartment just as World War II is ending and the German leaders are dead. Lee Miller (Kate Winslet) takes off her clothes so she can be photographed taking a bath in Hitler’s tub. This moment brings together several of the conundrums at the heart of “Lee,” the story of a real-life woman who revealed others and concealed herself, a model muse and artist working with the artificial and imaginary who became a war correspondent struggling to convey the indescribable. It’s telling that, after spending the war as a journalist, photographing wrenching horrors, including some of the first photos of the concentration camps, Miller returned to the staged, absurdist aesthetics of her earlier years. There, she worked with surrealists like Man Ray to create this very staged photo, moving the photo of Hitler to the edge of the tub and scraping the mud on her boots from a concentration camp on the pristine bathmat. Over the credits, we see the re-created photo along with the original.

Once the war was over, she didn’t talk about it. Miller’s son, Antony Penrose, knew nothing of his mother’s wartime photographs until he found them in the attic after she died. She had no problem sharing her body. We see her casually remove her shirt at a merry al fresco luncheon with friends from the art community. She describes herself as being done living a life as “the model, the muse, the ingenue… only good at drinking, having sex, and taking pictures.” She reveals almost nothing about herself until a scene late in the film when she tells her editor (the always superb Andrea Riseborough) about a profoundly traumatic experience from her youth. Winslet is heartbreaking here as she struggles between shame, fear, and fury. Part of her wants to tell the story, but she was raised to keep secrets. Perhaps she is so committed to telling others’ stories because of the pain of hiding her own, even from herself. The only other time we glimpse her as vulnerable is in a couple of moments where she sympathizes with or protects a woman.

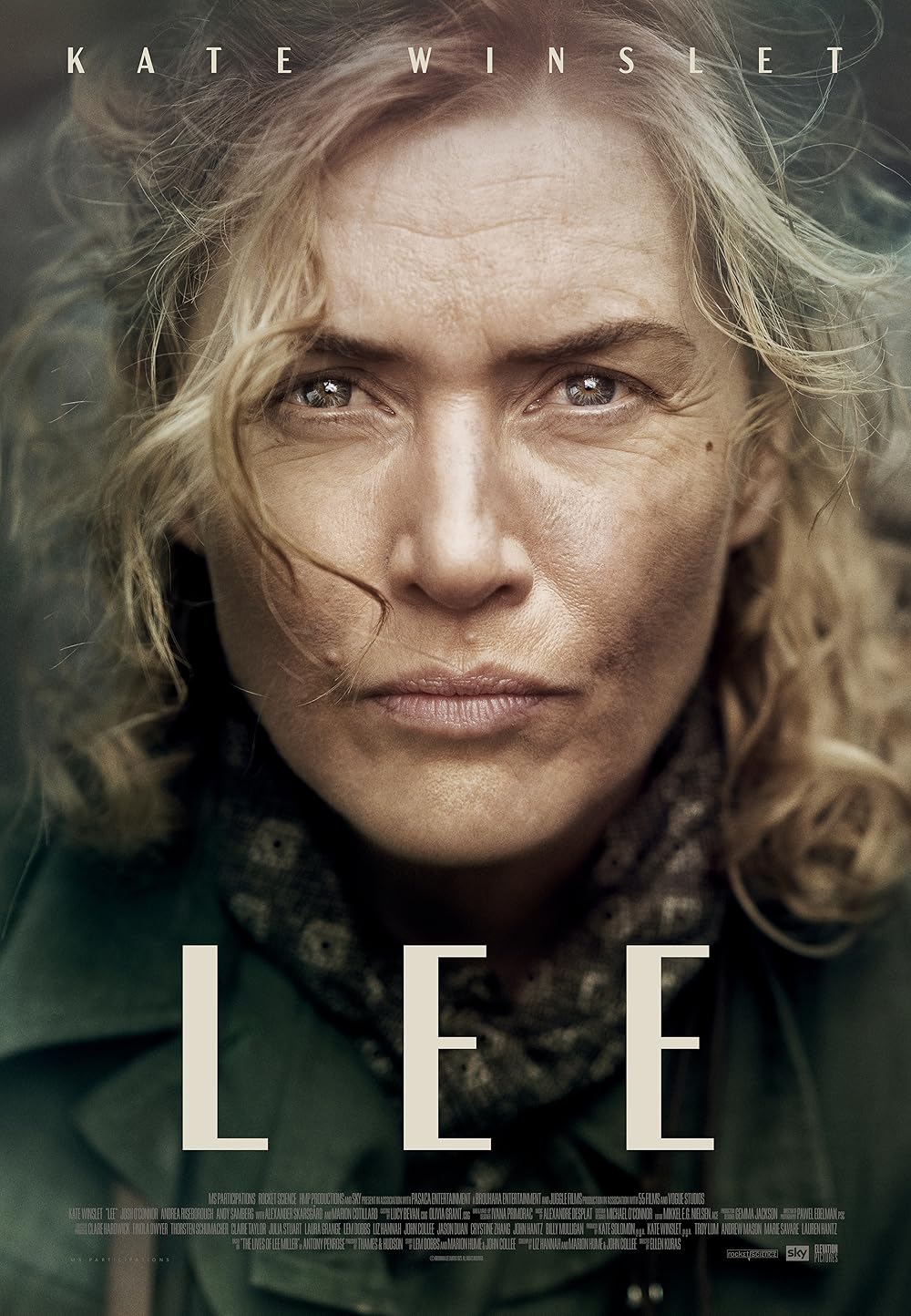

That creates a problem for the film and may be one reason the production struggled to get made for eight years. Miller, as portrayed on screen, is gruff, grim, and stoic for most of the story, and we seldom get to see what she is thinking and feeling. Even though we’re meant to be seeing a previously untold story of a heroic, impactful woman, it assumes we come to it knowing more than today’s audiences are likely to (how many will recognize Cecil Beaton?), leaving the story feeling empty. It is more about “then this happened, and then this other thing happened” than who Miller was, why she did what she did, and how it affected her. There’s a small twist at the end when we discover the identity of the man who has been trying to interview her in the 1970s (an earnest but empathetic Josh O’Connor), and even then the reality behind those scenes is not as impactful as it tries to be.

When the war begins, Miller gets a photography job with British Vogue, which has been directed “to encourage the women of Britain to do their duty” by bringing the urgency of what’s happening into the pages of a fashion magazine. At first, she takes pictures of the Blitz, “bombs, chaos, but everyone carried on, and I did what I could to capture it.” And then she is embedded with the American forces. Told that no women are allowed, she wanders off to where the women in the military are staying, spots a copy of Vogue with her photos, and takes pictures, including one of the women’s nylon stockings drying in a window, a powerful image of carrying on.

First-time director Ellen Kuras is an accomplished cinematographer who has worked memorably with Winslet in “Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind” and “A Little Chaos.” She’s a better visual fit with her photographer subject than the narrative. The images are strikingly framed, and we can tell how much Miller cares about what she’s doing as she quietly looks down to capture intimate and heartbreaking moments. She has a waist-level-finder camera typical of the era, which enables us to see her intent, magnetic face. Kuras understands the unique position of the photographer as intrusive but unobtrusive, sensitive enough to see where the story is but removed enough to maintain observer status. However, as for more about who she was, Miller stays frustratingly out of focus.