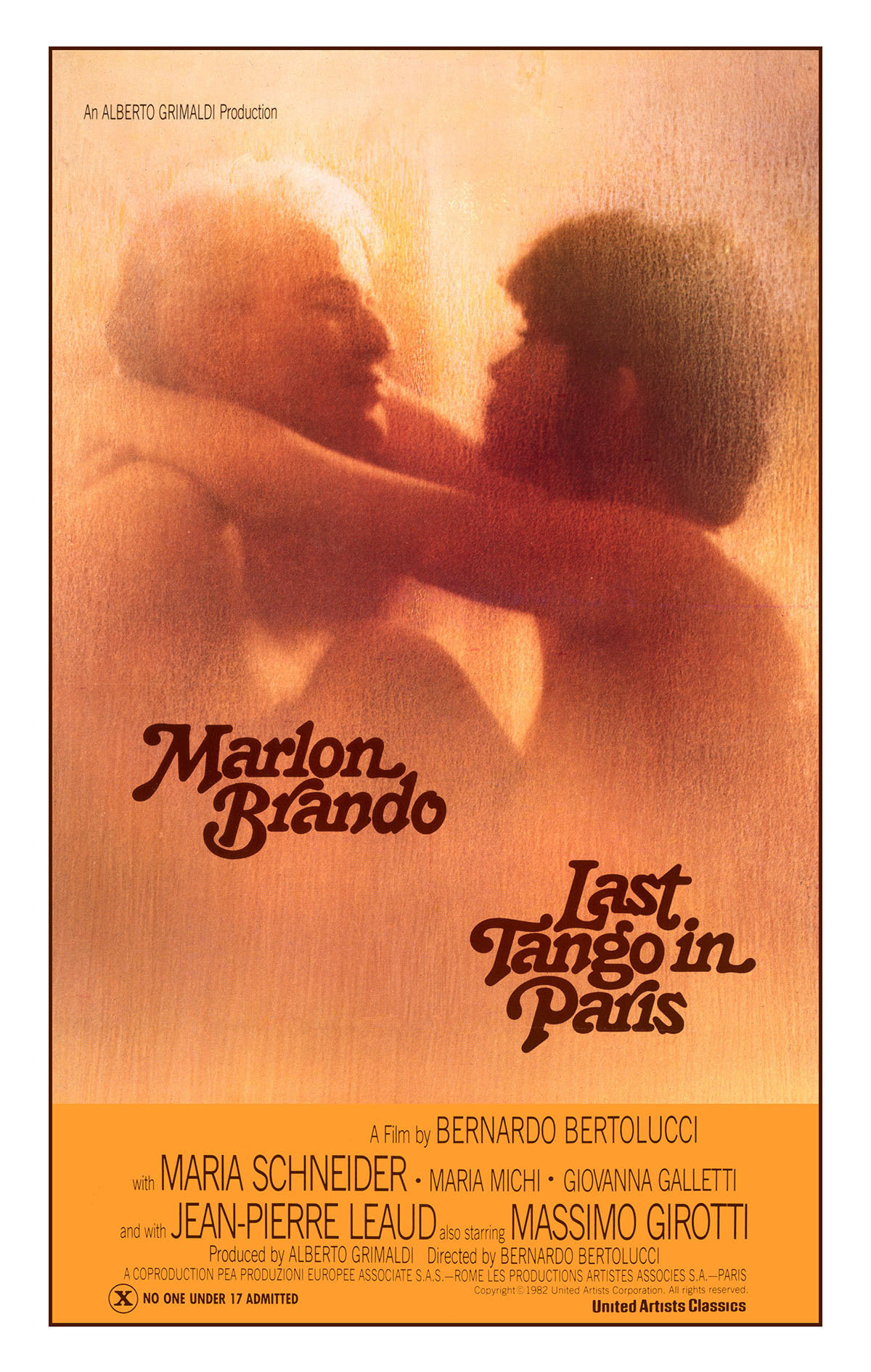

Watching Bernardo Bertolucci’s “Last Tango in Paris” 23 years after it was first released is like revisiting the house where you used to live, and did wild things you don’t do anymore. Wandering through the empty rooms, which are smaller than you remember them, you recall a time when you felt the whole world was right there in your reach, and all you had to do was take it.

This movie was the banner for a revolution that never happened.

“The movie breakthrough has finally come,” Pauline Kael wrote, in the most famous movie review ever published. “Bertolucci and Brando have altered the face of an art form.” The date of the premiere, she said, would become a landmark in movie history comparable to the night in 1913 when Stravinsky’s “Rites of Spring” was first performed, and ushered in modern music.

“Last Tango” premiered, in case you have forgotten, on Oct. 14, 1972. It did not quite become a landmark. It was not the beginning of something new, but the triumph of something old – the “art film,” which was soon to be replaced by the complete victory of mass-marketed “event films.” The shocking sexual energy of “Last Tango in Paris” and the daring of Marlon Brando and the unknown Maria Schneider did not lead to an adult art cinema. The movie frightened off imitators, and instead of being the first of many X-rated films dealing honestly with sexuality, it became almost the last. Hollywood made a quick U-turn into movies about teenagers, technology, action heroes and special effects. And with the exception of a few isolated films like “The Unbearable Lightness of Being” and “In the Realm of the Senses,” the serious use of graphic sexuality all but disappeared from the screen.

I went to see “Last Tango of Paris” again because it is being revived at Facets Multimedia, that temple of great cinema, where the largest specialized video sales operation in the world subsidizes a little theater where people still gather to see great films projected through celluloid onto a screen. (I am reminded of the readers in Truffaut’s “Fahrenheit 451,” who committed books to memory in order to save them.) It was a good 35-mm. print, and I was drawn once again into the hermetic world of these two people, Paul and Jeanne, their names unknown to each other, who meet by chance in an empty Paris apartment and make sudden, brutal, lonely sex. Paul’s marriage has just ended with his wife’s suicide. Jeanne’s marriage is a week or two away, and will supply the conclusion for a film being made by her half-witted fiance.

In anonymous sex they find something that apparently they both need, and Bertolucci shows us enough of their lives to guess why.

Paul (Brando) wants to bury his sense of hurt and betrayal in mindless animal passion. And Jeanne (Schneider) responds to the authenticity of his emotion, however painful, because it is an antidote to the prattle of her insipid boyfriend and bourgeoise mother. Obviously their “relationship,” if that’s what it is, cannot exist outside these walls, in the light of the real world.

The first time I saw the film there was the shock of its daring. The “butter scene” had not yet been cheapened in a million jokes, and Brando’s anguished monologue over the dead body of his wife – perhaps the best acting he has ever done – had not been analyzed to pieces. It simply happened. I once had a professor who knew just about everything there was to know about “Romeo and Juliet,” and told us he would trade it all in for the opportunity to read the play for the first time. I felt the same way during the screening: I was so familiar with the film that I was making contact with the art instead of the emotion.

The look, feel and sound of the film are evocative. The music by Gato Barbieri is sometimes counterpoint, sometimes lament, but it is never simply used to tell us how to feel. Vittorio Storaro’s slow tracking shots in the apartment, across walls and the landscapes of bodies, are cold and remote; there is no attempt to heighten the emotions. The sex is joyless and efficient, and beside the point: Whatever the reasons these two people have for what they do with one another, sensual pleasure is not one of them.

Brando, who can be the most mannered of actors, is here often affectless. He talks, he observes, he states things. He allows himself bursts of anger and that remarkable outpouring of grief, and then at the end he is wonderful in the way he lets all of the air out of Paul’s character by turning commonplace with the speech where he says he likes her. The moment is wonderful because it releases the tension, it shows what was happening in that apartment, and we can feel the difference when it stops.

In my notes I wrote: “He is in scenes as an actor, she is in scenes as a thing.” This is unfair. Maria Schneider, an unknown whose career dissipated after this film, does what she can with the role, but neither Brando nor Bertolucci was nearly as interested in Jeanne as in Paul. Because I was young in 1972, I was unable to see how young Jeanne (or Schneider) really was; the screenplay says she is 20 and Paul is 45, but now when I see the film she seems even younger, her open-faced lack of experience contradicting her incongruously full breasts. Both characters are enigmas, but Brando knows Paul, while Schneider is only walking in Jeanne’s shoes.

The ending. The scene in the tango hall is still haunting, still part of the whole movement of the third act of the film, in which Paul, having created a searing moment out of time, now throws it away in drunken banality. The following scenes, leading to the unexpected events in the apartment of Jeanne’s mother, strike me as arbitrary and contrived. But still Brando finds a way to redeem them, carefully remembering to park his gum before the most important moment of his life.