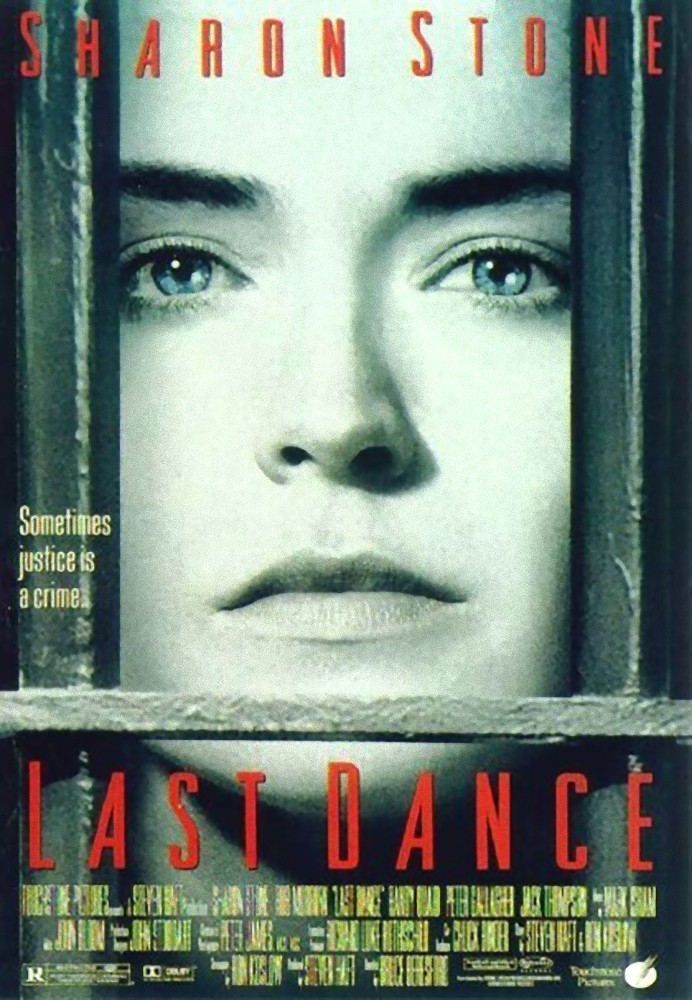

“Last Dance” stars Sharon Stone as a woman who has spent 12 years on Death Row after being convicted of two murders. Now her appeals seem exhausted, and her execution date draws near. A state-appointed attorney looks into her case and thinks there are grounds for appeal. But the state governor is a hard-liner who almost never grants stays of execution. And the woman herself doesn’t much prefer a life sentence to death. This is potentially powerful material, and the movie handles it thoughtfully. It makes a good showcase for Stone, who wants to be taken seriously as more than Hollywood’s favorite femme fatale. She does a good job of disappearing into the role; there are no leftover glamour touches or star turns, and I was reminded a little of Susan Hayward’s Oscar-winning work in “I Want to Live” (1958). After Stone’s interesting work in “Casino” and “Diabolique,” it is a reminder of how easy it is to stereotype an actress on the basis of a few famous sex-and-violence roles, and how unfair.

But the movie suffers from one inescapable misfortune: It arrives while “Dead Man Walking” is still fresh in our memory. That film was an unquestioned masterpiece, containing some of the best writing, acting and directing of recent years. “Last Dance” can’t stand up against it. Too many of its scenes are based on conventional ideas of story construction. We can see the bones beneath the skin.

Stone’s heroine, Cindy, is a disadvantaged child of an abusive home, who was exposed to sex and drugs at an early age and was on crack continuously for two days before she committed murder, a fact not brought up at her trial.

There are other circumstances about the murders that might also have interested a jury, but she received a poor defense, missed a chance at a plea bargain, and now faces death by lethal injection. Her lawyer is named Rick Hayes (Rob Morrow, from “Quiz Show”).

He’s not much of a legal brain. He got his state job because his brother (Peter Gallagher) is an aide to the governor. His boss (Randy Quaid) wonders what kind of an applicant turns up late for a job appointment, with wine on his breath.

There are two famous convicts on Death Row: Cindy, and a black man named John Henry Reese (Charles Dutton), who has masterminded an effective campaign to get his sentence commuted. “How they gonna go and kill a man who’s been on the New York Times best-seller list?” he asks. The governor (Jack Thompson) is a defender of the death penalty, but it appears that if he pardons anybody, it will be the other convict and not Cindy. She doesn’t much care. She distrusts everybody, is disillusioned with appeals, doesn’t want to spend the rest of her life in prison, and refuses to fight for her own life. Rick tries to break down her reserves, and eventually does so (“What have you got to lose?”). But these scenes owe more to movie conventions than to psychological truth. By helping her, he’s helping himself, and finding the self-respect he lost as a kid growing up in the shadow of a successful older brother.

The movie has a few scenes that really should have been rewritten before filming. One is the unconvincing moment when Rick awkwardly confronts the governor in the worst possible way, at the worst possible moment, to demand clemency for his client. Another is when Cindy’s former boyfriend attacks Rick during a prison interview; the scene plays as action, not drama. And why is it that all movies about execution always hinge on a phone call–and the call never comes until seconds before midnight? What are judges waiting for? What if they get a busy signal? Why can’t they call in at 11:30? Because they’re creatures of plot mechanics, that’s why.

Among the very best scenes in “Last Dance” are those leading up to the possible execution. Rick buys Cindy a dress she can wear into the death chamber, and as she unpacks it, the moment becomes very moving. And then there is the matter-of-fact way the prison officials go about their duties. “This is hard for everyone,” the warden says, not very helpfully, “but together, we’re going to get through it.” Stone can be proud of her work in this movie, but the material is simply not as good as it needs to be, after “Dead Man Walking.” That film reinvented the Death Row genre, saw the characters and the situation afresh, asked hard questions, and found truth in its dialogue. “Last Dance,” by comparison, comes across as earnest but unoriginal. It might have seemed better if it hadn’t been released in the shadow of “Dead Man Walking,” but we’ll never know.