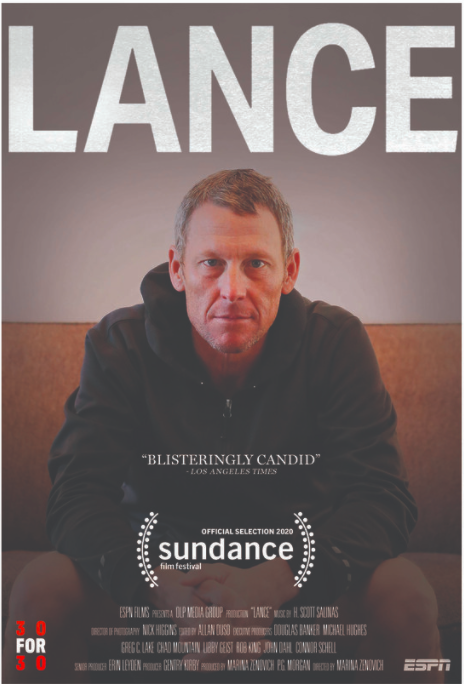

Lance Armstrong is a study in whether or not one can hold two competing thoughts in their head about a person at the same time. On one side of the human ledger, Armstrong wasn’t just a man who violated the rules of his sport, but one who bullied and attempted to destroy anyone who blew the whistle on him. On the other side, his work with cancer awareness and patient navigation through Live Strong has undeniably saved thousands of lives. The brilliance of Marina Zenovich’s “Lance,” which airs in two parts on ESPN this Sunday night and next week, is how keenly it illustrates this angel-demon dynamic of its subject, spotlighting how both of them live in the same person. Everyone who watched the “The Last Dance” for the last five weeks on the sports network that no longer has sports to air owes it to themselves to watch “Lance,” another study of a man often called a bully, often called a hero, and who is endlessly fascinating.

The main difference between the two is one of access/control. Several people have commented on how much “The Last Dance” leans into hagiography, and how Michael Jordan himself clearly controlled the entire narrative. (Ken Burns went as far as to say it’s not really a documentary.) “Lance” is not a puff piece, but Zenovich is too smart to turn it into a direct hit piece either.

“Lance” opens with ESPN journalist Bonnie Ford talking about how she would be surprised if Lance Armstrong didn’t try to shape the narrative in Zenovich’s film. The genius of the film is that Zenovich then essentially leans into that, allowing Armstrong the freedom to at least think he’s controlling the story. She opens the film with Lance telling a story about a bunch of guys at a bar who shouted “f**k you” at him. It’s a tone-setter in that Armstrong talks about how a younger version of him would beat the guys up, but a more mature Armstrong paid for their drinks and made sure the bartender told them he did it with love. He thinks this example shows his maturity and how he essentially got the upper hand through benevolence. He doesn’t pause to consider the fact that a bunch of guys hated him enough to shout profanities at him. Or that it will happen for the rest of his life. Zenovich is a master at allowing her subject just enough rope to hang himself, letting Lance tell his own stories in a way that illuminate his selfish, shallow perspective. He may be crafting the narrative, but Zenovich is revealing the truth embedded in how he crafts that narrative.

“Lance” proceeds chronologically for most of its runtime, returning to interviews with Armstrong and other major players to tell his life story. And so we get the expected chapters about his early childhood, teen mother, abusive father figures, and his early days in sports, but even these are tinged with what we know is going to come. For example, Terry Armstrong, Lance’s one-time stepfather, openly suggests that whipping his son gave him the drive to be a champion before pausing to consider if it also gave him a dangerous “succeed at all costs” worldview. I usually come down on chronological docs, but “Lance” isn’t traditional in that sense. Not only is Armstrong a forthcoming and compelling interview subject, but everything feels subtly placed in the context of the overall picture of his life.

Do not come to “Lance” expecting an open-armed quest for forgiveness or understanding. Armstrong understands that a lot of people are like those guys who yelled at him at the bar and will never forgive or attempt to understand what he did. And Armstrong is still stubborn in the manner in which he blames others for his downfall, especially Floyd Landis. He’s not here for your forgiveness and he fully believes he’s been thoroughly punished. At one point, he argues that he’s paid for his sins because of all the endorsements he lost and the lawsuits he faced. As someone points out, that’s like believing you paid your dues after robbing a bank because you had to give the money back.

And that’s the line Zenovich walks throughout her film, allowing us to see Armstrong in all his intricacies. The truth is that Armstrong’s doping shouldn’t diminish what he’s done for cancer research, but his cancer research shouldn’t excuse his doping. In the end, “Lance” allows a deeper understanding of this very complex public figure, someone who did an amazing amount of good in the world but also fell hard from one of the greatest heights in sports history. Bonnie Ford may be right that Armstrong tries to write his own story in “Lance,” but Zenovich never takes her hand off the pen.

Airs on ESPN on 5/24 and 5/31.