Imagine wandering into a cozy London pub one quiet afternoon and finding yourself quaffing pints alongside a ferociously charming, craggily handsome older gent, a survivor of the Swinging ‘60s who regales you with a torrent of tales about that storied era and his own place near the center of its rock ’n roll and arts scene. It’s a fascinating aural journey, at least until the raconteur’s garrulousness means that he rambles on a bit too long and, in so doing, comes to seem less illuminating than self-involved.

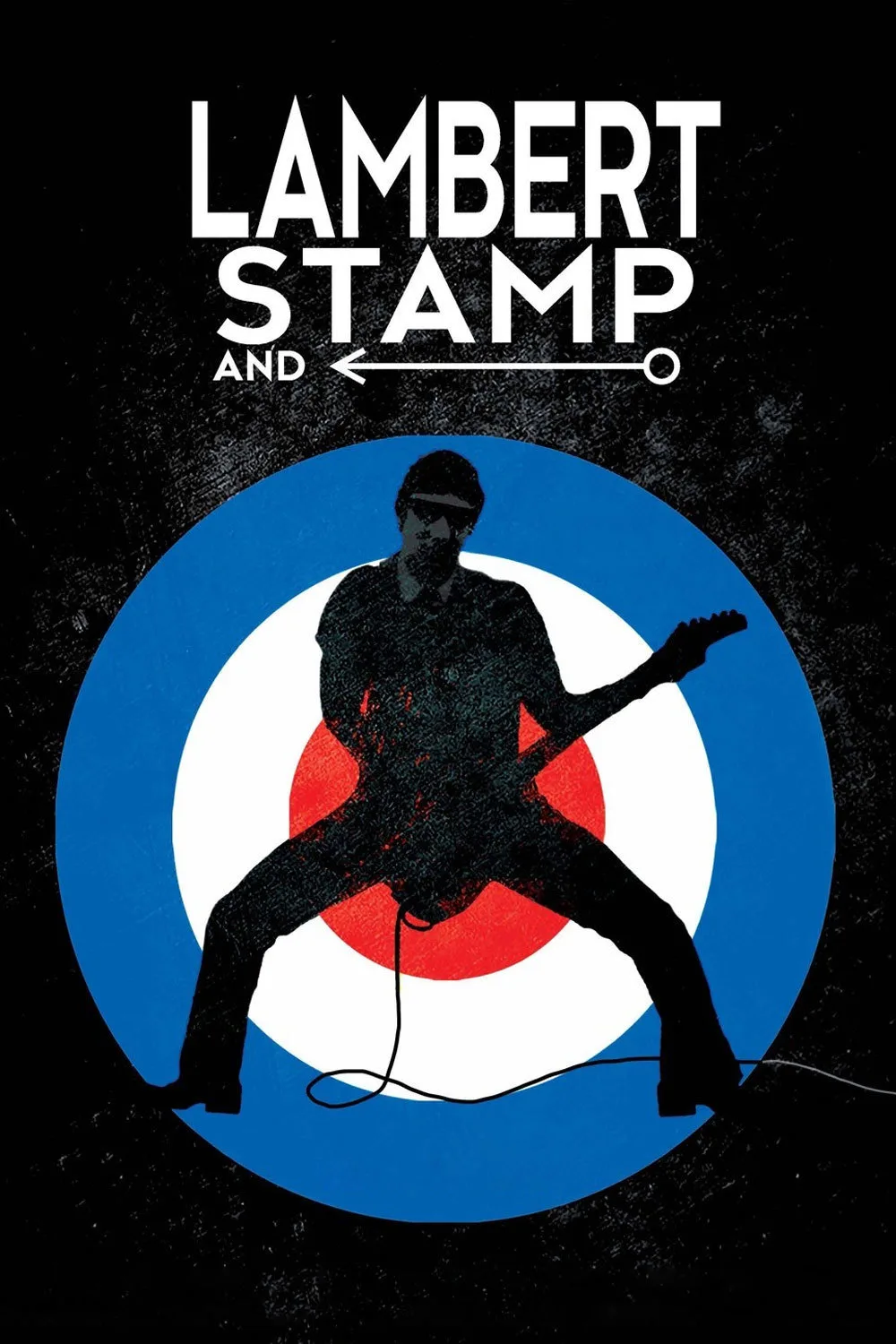

That’s something like the experience of watching James D. Cooper’s “Lambert & Stamp,” a sharply crafted, highly entertaining portrait of two young Londoners who made their names and fortunes by managing a fledgling band called the High Numbers, who became The Who. Not only an involving account of that group’s rise from obscurity to superstardom, the film is also an exceptionally vivid and evocative depiction of the cultural flux of the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. That it ends up seeming longer than it need be, and somewhat muddled in its last half hour, are significant flaws but will be forgiven by viewers drawn to the film’s colorful subject matter and central characters.

The era was one of illustrious talent managers, and if Kit Lambert and Chris Stamp never achieved the celebrity of The Beatles’ Brian Epstein or the Stones’ Andrew Loog Oldham, that certainly was not due to any lack of personal charisma on their part, though it might be said that their charisma was more collective than individual. The odd couple of British rock managers, they were a delightfully unlikely duo, Lambert a gay, upper-class Oxford-educated intellectual, Stamp a brawling East Ender whose chiseled looks mirrored those of his movie star brother, Terence. The two were drawn together by a mutual love of cinema, especially the French New Wave. Since making one’s own movies then was not as easy as it is now, they decided they would slip into film by the back door, as it were, by finding a great band to manage and making a movie about them.

The second half of that plan never came to pass, but the first half did, in spectacular fashion. Drawn into a “grotty” nightclub by a line of Mod motor-scooters outside, the band-hunters came upon of roomful of pimply teens mesmerized by the aggressive noise created by Peter Townshend, Roger Daltrey, John Entwistle and Keith Moon. On his first encounter with the would-be managers, Townshend recalls, it was, for him, love at first sight. But Lambert and Stamp’s friends didn’t feel the same: the musicians, they said, were simply too ugly to be pop stars.

One benefit of its protagonists’ cinematic aspirations is that there’s great b&w 16mm footage of the band and its fans at this early stage, even before they became The Who. Lambert and Stamp themselves are also well documented. There are also copious stills of them hanging out with the likes of Jimi Hendrix, as well as enough footage of them together that you get a real sense of the emotional bond between the two dapper scene-makers. An added plus are interviews in which Lambert expounds on British youth culture in fluent French and German for foreign TV interviewers.

While the film doesn’t delve into the specifics of how Lambert and Stamp shaped the band’s creative profile – nor, rather curiously, is much said about the particular challenges faced by second-wave British Invasion bands – there’s no doubt that the two were concerned with lots more than the business end of things. Lambert, whose father was a noted symphony conductor, had Townshend move into his and Stamp’s flat in posh Belgravia (where, hilariously, they were able to live more cheaply since the local merchants were used to extending long lines of credit to aristos) and introduced him to classical music and composers such as Purcell. Townsend allows that this education and other mentoring activities by Lambert had a crucial impact on his songwriting.

The film’s lengthiest and most important interviews are with Townshend, Daltrey and the voluble Stamp (Lambert died in 1981), and all agree that, though The Who were international hit-makers by the late ‘60s, it wasn’t until the release of “Tommy” in 1969 that the band felt firmly established both creatively and commercially. Townshend recalls thinking of Daltrey as an actor who blossomed as a singer/frontman once the rock opera gave him his greatest role.

There are glimpses of topnotch Who performances in this account, but only glimpses. Fans who want more tunefulness should look to concert films or other docs. Though it shows us plenty of the band’s destruction of their instruments (a gimmick that became a trademark), “Lambert & Stamp” is one of those films that lets talking heads and their words take precedence over music, which will be frustrating for some viewers.

After “Tommy,” the four musicians and their two managers were all rich (The Who eventually bought Shepperton Film Studios), and a certain amount of dissolution set in. Stamp saw his dream of directing a movie of “Tommy” pass to Ken Russell. Lambert bought a palazzo in Venice and became addicted to heroin. Moon died in 1978, Entwistle in 2002.

While chronicles like this one almost invariably are more engaging in showing the rise to fame rather than the decline from it, “Lambert and Stamp” is over-long at 117 minutes and begins to feel meandering and somewhat clotted in its last quarter. The post-“Tommy” unraveling may have been murky in reality, but the telling here makes it more so. One glaring omission concerns the death of Lambert: We’re not told when, where or how it happened, or how it affected the band or Stamp. That’s unfortunate both in itself and in how it tends to tilt the film to Stamp, who, while very personable, ends up seeming a bit self-serving due to the screen time and narrative dominance that Cooper allows him.