When conversations about America’s racist past hit a fever pitch in 2020 after the murder of George Floyd, members of the Lakota Nation joined in protest. As Confederate monuments were being toppled one by one, they called for the restoration of one of their sacred sites. The Black Hills in South Dakota, the cradle of their civilization, had been defaced with the visages of four white presidents decades before. If we could crumble the statues built to the oppression of others elsewhere, why not address Mt. Rushmore and all that it represents?

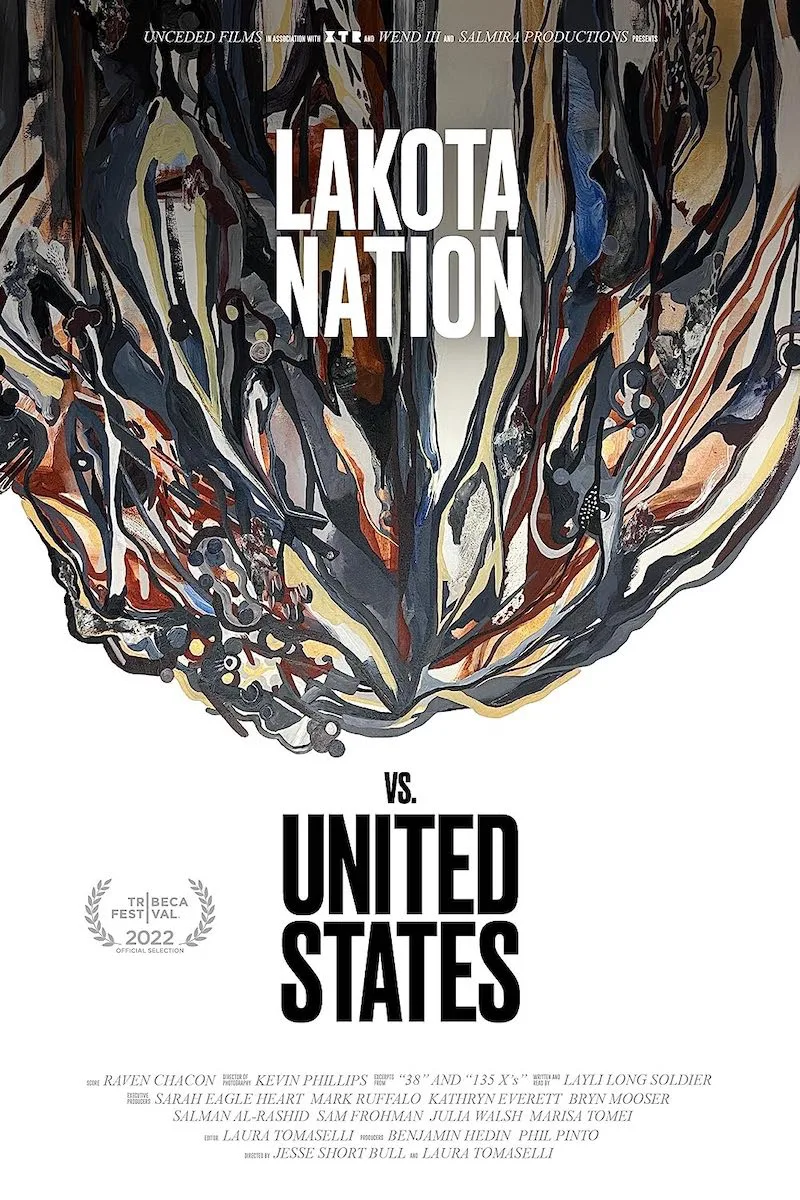

That is just one of the questions and stories in directors Jesse Short Bull and Laura Tomaselli’s searing documentary, “Lakota Nation vs. United States.” Writer and poet Layli Long Soldier’s melodious narration leads the film through an expansive view of the systemic ways the U.S. stripped Indigenous communities from their land, denied them their rights, forbade them their language and culture, murdered generations, abused their children in residential schools, and to this day, continue to harm their communities by trying to extract natural resources and pollute their endangered lands. The film is a history lesson, a poetic cry for justice, a testament to the Lakota Nation’s resilience and acknowledgment of the community’s loss—an incalculable loss that can never be fixed with underwhelming financial reparations—from the U.S. government’s 150-year betrayal of their people.

“Lakota Nation vs. United States” moves swiftly but thoughtfully through various topics, covering issues like the over 400 land-grabbing treaties that robbed tribes of their homes to historic confrontations from the Battle of Little Bighorn and water protection protests at Standing Rock. Voices of modern-day Lakota activists and elders connect the past to the present, explaining how the treaties and mistreatment of their people in days past have hurt the generations since. This emotionally resonates when retracing the harrowing development of residential schools, which sought to “kill the Indian, save the man,” and the lasting harm it did to rip a culture out of the hearts of its children—if they survived.

Oral histories weave between the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries in a dreamy nonlinear narrative path written by Long Soldier, Benjamin Hedin, and Laura Tomaselli. Delicately constructed, the narrative shows how systemic dehumanization disenfranchised and villainized Indigenous people and justified their mistreatment in the eyes of white colonists who saw them as savages. But all this leads to the film’s hope for better days ahead, a future that returns the land to its original Lakota stewards.

Throughout the film, directors Short Bull and Tomaselli couple numerous interviews that personalize the Lakota Nation’s heartaches with montages of archival documents, old news reports, and mesmerizing footage steeped in the natural beauty of the Black Hills. Together, they illustrate the confounding legalese that took millions of acres away from tribes, examine the way media stereotyped Indigenous groups in cartoons and movies (like an abbreviated version of Neil Diamond’s “Reel Injun”), and documented the many painful rewritings of history that erased bloodstains off the records of beloved presidents and historical figures who carried out atrocities in the name of manifest destiny.

In the U.S. government’s crusade to make the West “safe” for white settlers, untold horrors happened and continue to happen. While history books reimagine cowboys and the General Custers to be the good guys, films like “Lakota Nation vs. United States” are a necessary and vital correction. They are a collection of the living legacies petty tyrants and racist politicians have sought to silence. The Indigenous activists’ ongoing advocacy work is a radical act of defiance, a forceful stop to having their story whitewashed and written for them by outsiders. With its methodical approach, the documentary exhumes the nearly forgotten past, exposes assimilation as a form of violence, and explores how private ownership and capitalism have displaced generations of Lakota from their ancestral homes. “Land Back is a war cry for the liberation of my people,” one activist tells the camera.

For all the tragedy in the past, the movie ends with a look towards the future and a hope for the next generation. The movement moves towards a better tomorrow if only people outside the Lakota Nation will embrace and support their efforts.

Now playing in theaters.