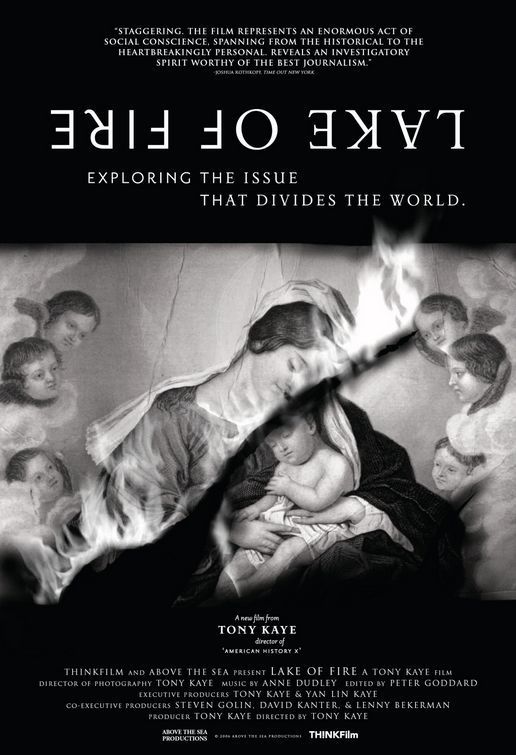

Readers often complain about documentaries that don’t tell “both sides.” Those who care deeply about the issue of abortion in America, no matter which side they are on, may complain that “Lake of Fire” tells the other side. This is a brave, unflinching, sometimes virtually unwatchable documentary that makes such an effective case for both pro-choice and pro-life that it is impossible to determine which side the filmmaker, Tony Kaye, stands on. All you can conclude at the end is that both sides have effective advocates, but the pro-lifers also have some alarming people on their team.

One is an earnest young man named Paul Hill, neat haircut, aviator glasses, who says we should execute all abortionists. He doesn’t stop there. We should also execute all blasphemers. What is a blasphemer? he’s asked. Well, he says, people who say “God damn it.” Anyone who says “God damn it” should be executed? “Yes,” he says firmly. Later, he murders a Florida doctor who performed abortions. It’s one of two murders in the film which result in the death penalty, which pro-life advocates generally support.

Other pro-lifers buy property next to abortion clinics and build platforms so they can climb onto them and shout over fences at young women entering the clinics. They consider abortion to be murder, plain and simple, and they are also against birth control and sex education, which have proven to reduce unplanned pregnancies and therefore abortions.

On behalf of their argument, Hill shows graphic footage of abortions and their consequences. The scene that shook me most deeply has a doctor sorting through a pan of blood, fluid and body parts to be sure he has removed an entire fetus. Tiny hands and feet can clearly be seen. Throughout the film, we see more than enough to convince us that what is being aborted is often recognizably human.

The sanest voice of reason on the pro-life side is Nat Hentoff, the veteran left-wing writer for the Village Voice, described as a civil libertarian and an atheist. He argues from a logical, not religious, point of view that when a sperm and an egg unite, a human is being formed, and the process should not be interrupted. His dispassionate remarks, whether you agree with them, are a calm center in a strident storm.

Another key witness in the film is Norma McCorvey, who was the anonymous “Jane Roe” in the 1973 Supreme Court decision Roe v. Wade. She was a pro-choice activist for years, had her home and car shot at, felt a virtual prisoner in her house, and then there was an unanticipated development. The property next door was purchased by anti-abortionists, she started to visit them, she found their office so calm and friendly that she was converted.

We also meet, anonymously, some of the young women who apply at abortion clinics, and hear their stories. And we hear grim statistics: If abortion is made illegal again in America, the abortion rate will remain about the same as it was before Roe v. Wade, but the fatality rate will start climbing. Before the Supreme Court decision, the leading cause of death among young women, we’re told, was not cancer, not heart disease, not accidents, but side-effects of illegal abortions.

The film has been a life’s work for Kaye, a British citizen, now 55, who has been filming it on and off for 17 years. He shot in 35mm wide-screen, using black and white (color would be unbearable). At 152 minutes, his film doesn’t seem long, because at every moment something absorbing, disturbing, depressing or infuriating is happening. True, he comes down on neither side of the debate. But what he shows inadvertently is how the tradition of freely exchanged ideas in America has been replaced by entrenched true believers who drown out voices of moderation.

Alan Dershowitz, the Harvard law professor, tells a parable that seems to apply. A rabbi is asked to settle a marital dispute. He hears the husband’s view. “You’re right,” he tells him. He hears the wife’s view. “You’re right,” he tells her. One of his students protests: “Rabbi, they both can’t be right.” The rabbi nods. “You’re right,” he says.