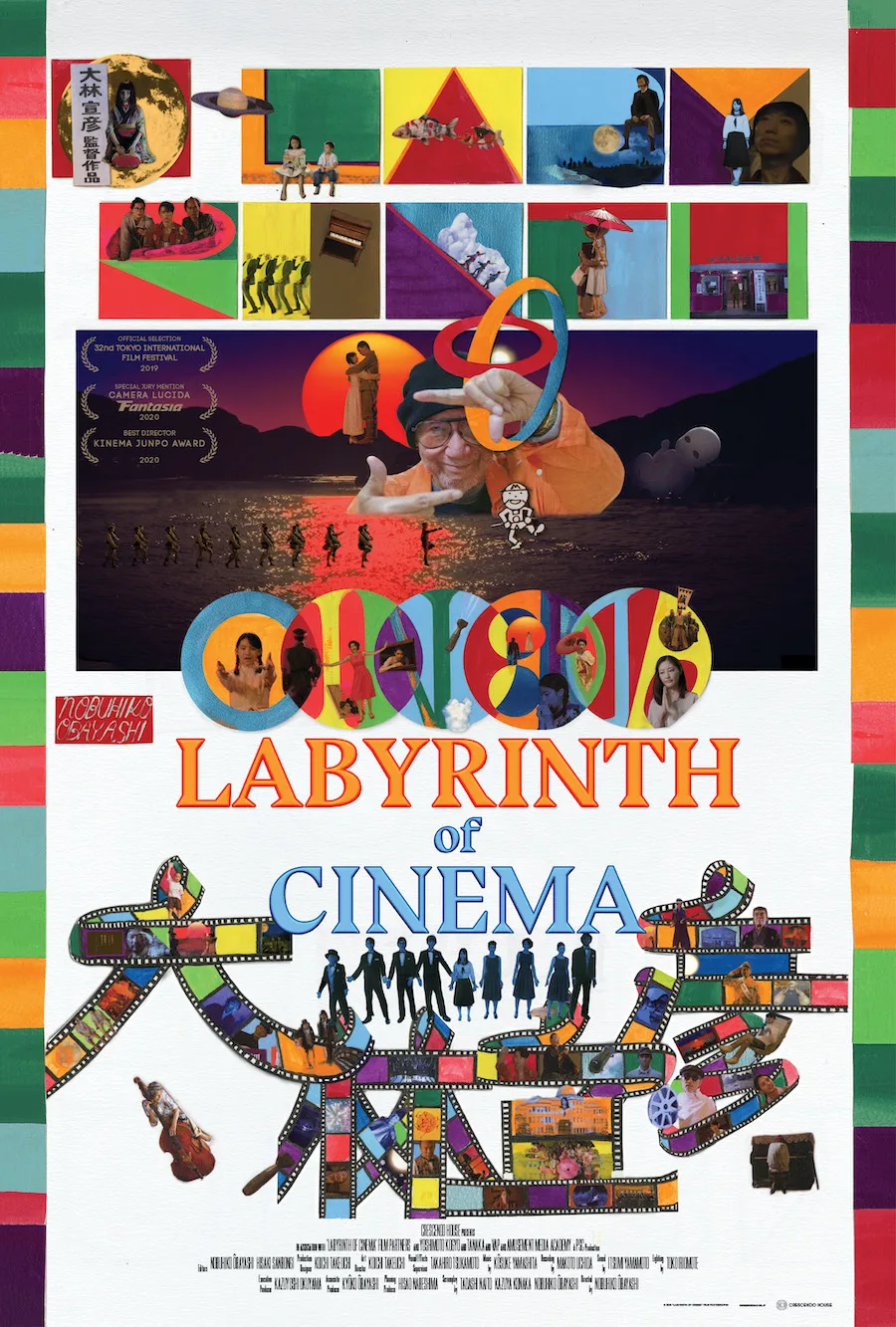

Japanese filmmaker Nobuhiko Obayashi was diagnosed with lung cancer in 2016, about three years before he completed “Labyrinth of Cinema,” a trippy anti-war drama about Japanese war movies, of which Obayashi re-creates, parodies, and criticizes in one long movie within his movie. Or really, it’s one long movie marathon within Obayashi’s movie since “Labyrinth of Cinema” takes place at an evening-long war film festival hosted by Setouchi Kinema, a small Hiroshima movie theater that’s putting on one last show before permanently closing.

The plot is simple enough to be irrelevant: three bright young things— teeth-picking film historian Hosuke (Takahito Hosoyamada), enthusiastic film buff Mario (Takuro Atsuki), and aspiring gangster Shigeru (Yoshihiko Hosoda)—chase after chaste 13-year-old Noriko (Rei Yoshida) after she tumbles into the Setouchi Kinema’s movie screen, and becomes part of Obayashi’s unstable meta-narrative. By the way: Obayashi died of lung cancer a year and a half ago. You can tell that his death weighed on him just by watching “Labyrinth of Cinema,” his last movie, a three-hour living will, and a dazzling curtain call.

The movie’s Hiroshima setting gives away its personal nature since Onomichi, Hiroshima is director/co-writer/co-editor Obayashi’s hometown and also the main location for some of his movies, including the 1983 bubblegum-psych fantasy “The Girl Who Leapt Through Time.” Obayashi is best known to American cinephiles as the director of the 1977 day-glo nightmare “House,” a fizzy horror-fantasy that only became an international cause célèbre in 2009 after it screened at the New York Asian Film Festival and a few other noteworthy events. In “Labyrinth of Cinema,” Obayashi (along with co-writers Kazuya Konaka and Tadashi Naito) tries to sum up what he’s learned and tried to convey through filmmaking in a volatile auto-critique of movies as both seductive propaganda and palliative empathy machines.

Obayashi uses green-screen technology and cheap (but effective) computer graphics to dramatize folksy anecdotes about filmmakers like John Ford and Yasujiro Ozu, which he sandwiches between brutal and/or sentimental episodes about local war crimes and counter-cultural resistance. Sometimes Obayashi quotes poetry, particularly by Chuya “Japan’s Rimbaud” Nakahara. Sometimes, a cartoon character or samurai folk hero (Musashi Miyamoto?!) steals a scene or two. A few characters, like the time-traveling authorial stand-in Fanta G (drummer Yukihiro Takahashi), talk about movies as a beautiful, essential lie that’s first used as a balm and a distraction, and then also considered as a runway to a brighter and still unimaginable future. You give Obayashi three hours of your time, and he’ll give you a brilliant headache.

You might watch “Labyrinth of Cinema” and wonder where the hell this all came from. Like Obayashi’s recent war trilogy (2011-2017), and many of his earlier features—and short movies and TV commercials—“Labyrinth of Cinema” constantly reminds you that it’s “A Movie.” Before Obayashi’s movies begin, the words “A Movie” are usually presented on-screen in a frame within the image’s frame. So in “Labyrinth of Cinema,” Obayashi’s characters are often re-framed by small circular frames within the camera’s frame. Sometimes these images flip around on-screen, so that a character who was on the left side of the screen is now upside, or on the right, as if they were in conversation with themselves, the viewer, and anyone else who’s watching. There are also a surprising number of fart jokes and some callbacks to older Japanese movies like “I Am a Cat,” “The Rickshaw Man,” and “Wife! Be Like a Rose.” “Labyrinth of Cinema” is a lot of movie.

Obayashi’s various projects are instantly recognizable, given his usual combination of mistrust and fascination with movies as an expression of wish fulfillment and nostalgia. So it’s not surprising that his view of the past—and the cinematic image—is never really seductive in “Labyrinth of Cinema.” Cheerfully naïve characters get lost in their companions’ comforting, half-remembered memories, and never stop to wonder why one thing inevitably leads to another, and another, and another. They float around on-screen, unmoved by the laws of gravity or physics and unable to hide in whatever photo-booth-quality backdrop surrounds them. Obayashi’s characters all half-know and half-hope that they’ll live to see the next scene, so they take their time learning how to ride the ever-breaking tidal wave of Japanese history according to Nobuhiko Obayashi.

“Labyrinth of Cinema” is tremendously affecting, frequently beguiling, usually exhausting, and on, and on, and on. An indulgent ramble from an innovative surrealist who was always sensitive and even suspicious of his own work’s impact—as a tool for advertising, political whitewashing, and pure sentimental indoctrination. On his out way the door, Nobuhiko Obayashi left us wondering how he got all the way from “House” to here without losing faith in humanity and his art; I don’t know, but “Labyrinth of Cinema” is still there anyway.

Now playing in select theaters.