While the new Netflix rom-com “La Dolce Villa” is not the unmitigated disaster that was “Mother of the Bride,” director Mark Waters’ previous outing for the streamer, I almost wished it were that bad so I would feel something other than boredom.

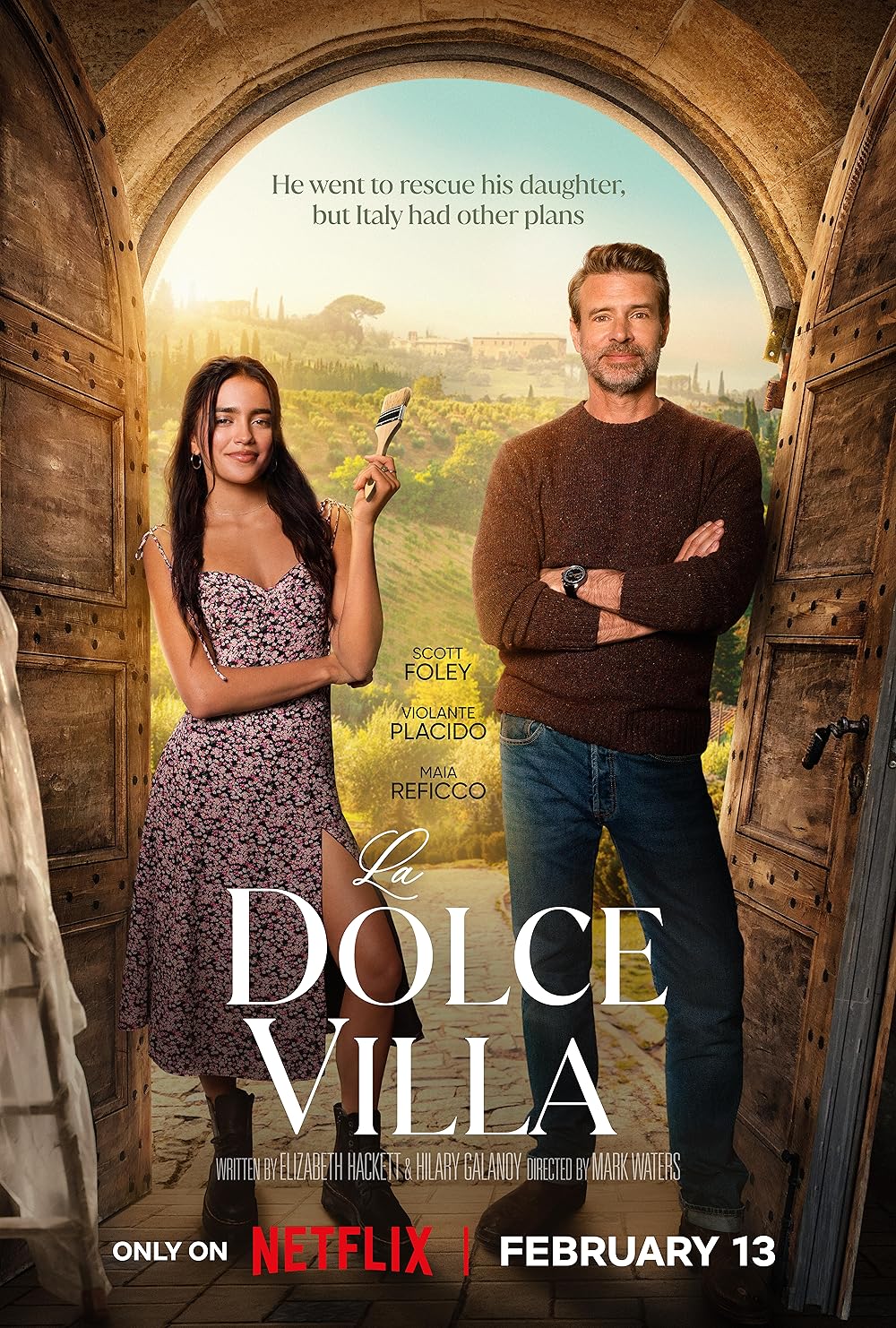

Set in rural Italy, the film centers on fifty-something widower Eric (Scott Foley), who is back in Italy despite having a “cursed” relationship with the country. He’s off to find his twenty-something daughter Liv (Maia Reficco), who is going to use her inheritance to buy a villa under a new economic plan in which small towns sell abandoned heritage villa “as is” for one Euro as a way of attracting new blood to their communities. Once he arrives in the village of Montezara, he meets the town’s Mayor, Francesca (Violante Placido), and together they hatch a plan to help his daughter turn her villa into a cooking school that might be an even greater economic boost for the town.

The inspiration for the film is clearly the far superior Diane Lane film “Under The Tuscan Sun,” in which Lane plays a recently divorced novelist who goes on a last-minute trip to Italy, buys a villa, and builds a whole new life for herself. Several plot points, and even the score, are unashamedly ripped off from that earlier film. The biggest difference between the two film is that “Under The Tuscan Sun,” which was written and directed by Audrey Wells and inspired by the popular memoir of the same name by Frances Mayes, savored the small details that make up a life and a community, like the taste of olives or the dirt and dust of renovating a space. And, of course, starred the luminous Diane Lane, fresh off her Oscar-nominated turn in “Unfaithful.”

Unfortunately, every script and directorial choice in “La Dolce Villa,” from the casting to the shallow characterizations and antiseptic production design, feels designed to be vapid background noise. There is no flavor for what living in the village is like, for the newcomers or those who have lived in it their whole lives. Although we get a few surface-level personal details about everyone, just about every character, lead or supporting, is either a cliché or used solely for exposition dumps.

After college, Liv, we’re told, did odd jobs in various parts of Italy, including nannying and teaching English, in order to reconnect with her late mother’s Italian heritage. It’s never clear what exactly she studied in college, or what she wants to do with her life other than live in Italy. Other than plodding expository conversations with her father, we don’t actually know how she feels about being in Italy. Eventually she befriends the contractor renovating the villa, who thinks she has potential as an interior designer, ostensibly because she can use the word “vibe” and pick out traditional paint colors, and sets her up with an internship working for his friend in Rome. Liv’s entire character journey, be it renovating the villa, her will-they-won’t-they relationship with a hot local chef named Giovanni (Giuseppe Futia), and her sudden internship are not well woven into the film, with Liv disappearing for so many long stretches of time that when she does reappear it’s almost jarring. Her scenes are also clipped and perfunctory, in favor of spending more time with the blossoming relationship between Eric and Francesca, which itself is overly orchestrated by plot mechanics and has absolutely no fire to it.

The phrase “Dolce far niente,” an Italian concept revolving around slowing your roll and enjoying the idle pleasures in life, is introduced to Eric by Francesca, although they both laugh it off because they are workaholics who agree that it’s people like them who keep the world running. It seems as though the script is setting it up so that eventually the two will learn to embrace this ethos. However, despite mentioning the phrase several times as they get into one absurd situation after another, everything they do still ladders up to the capitalistic goals of running a business, be it the villa-turned cooking school or the town.

All of the film’s ersatz plotting would maybe be worth it if the film actually bothered to capture anything memorable about Italy. Although Waters actually filmed on location in the country, he films most of the scenes in and around Tuscany and eastern Lazio as if they are set-ups for postcards–perfectly staged, but sterile and stripped of the messy sensuality of life. The countryside itself is filmed with a really hard, bright sunlight that somehow manages to flatten and wash out the beauty of the region. Leaving us with cardboard characters in a cardboard land.

Ultimately, “La Dolce Villa” is about as authentic an Italian experience as a night at the Olive Garden.

On Netflix now.