Before there were mega-churches the size of sports arenas preaching prosperity and weight loss, before televangelists and a billion-dollar “He gets us” ad campaign, back in the era of hippies and Woodstock and peace signs, there were people known as “Jesus freaks.” The generation that rebelled against the military-industrial complex, commercialism, their parents, and pretty much everything but was not always clear about what they wanted, included a sub-group who became passionate Christians. They weren’t in the mold of people dressed up for church on Sunday. They lived simply and communally. And they were inspired by leaders who were charismatic in both the secular and religious senses of the word.

They were the subject of a June 21, 1971 cover story in TIME Magazine titled “The Jesus Revolution.” “There is an uncommon morning freshness to this movement, a buoyant atmosphere of hope and love along with the usual rebel zeal,” the story gushed. “Their love seems more sincere than a slogan, deeper than the fast-fading sentiments of the flower children; what startles the outsider is the extraordinary sense of joy that they are able to communicate.”

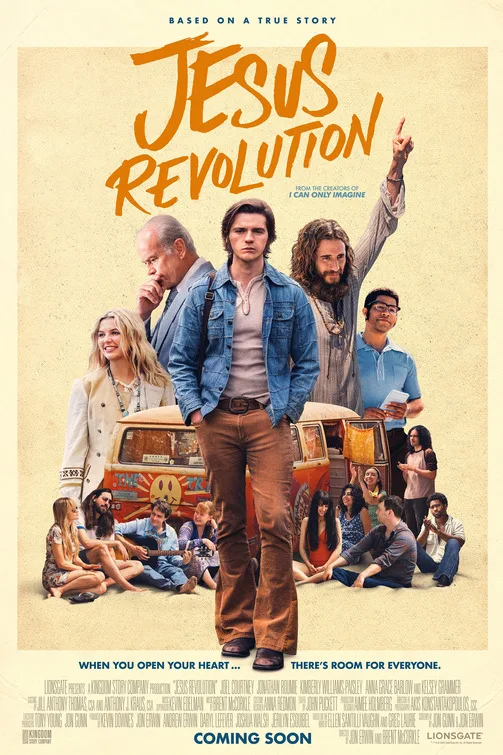

That is the story and the message of a new film, also called “Jesus Revolution,” based on a book by one of the leaders of the “Jesus freaks,” Greg Laurie. This movie is not about certain details, like one of its real-life characters’ homosexuality and history of substance abuse and instability. Nor does this film explore hard questions about how the cleansing of baptism does not necessarily lead to a perpetually “buoyant atmosphere of hope and love.” Instead, it’s a gently told story preaching to the converts, assuming that evangelical Christianity is unassailably the answer without considering this particular form of worship may not be the answer for all.

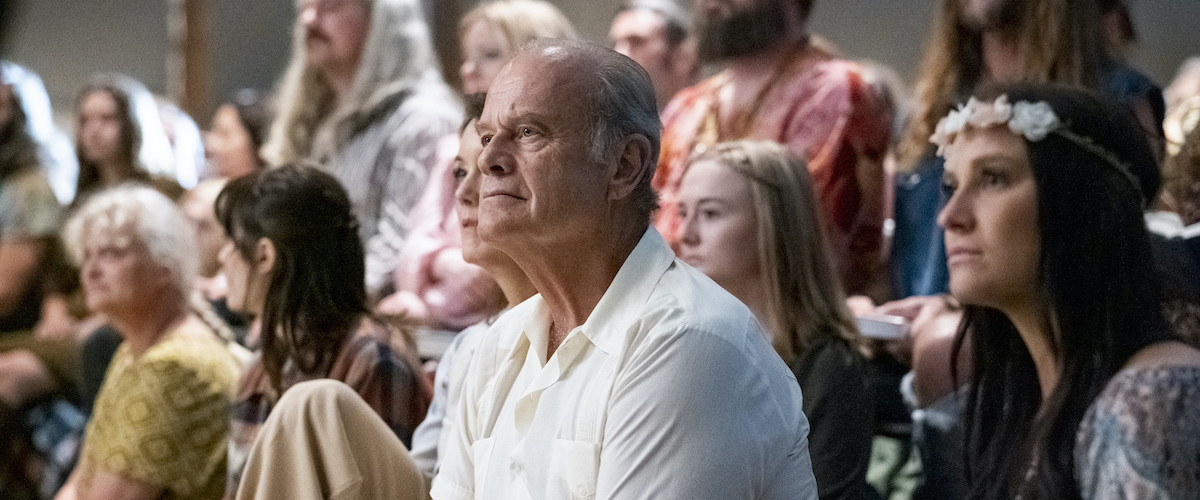

Kelsey Grammer plays Chuck Smith, a minister in California who presides over a traditional church named Calvary Chapel. Smith’s daughter persuades him to talk to the long-haired and improbably named Lonnie Frisbee (Jonathan Roumie). Initially certain that Frisbee is just an irresponsible hippie, Smith is impressed with his sincerity, humility, and dedication to the messages of Jesus about generosity and a spirit of welcome. Frisbee tells Smith there’s an opportunity to reach hippies because all of the things that worry him, their rejection of their parents’ values. Their experimentation with drugs is a search “for all the right things in all the wrong places.” He believes he can show them that the right place is God.

Smith brings Frisbee and his followers into his home and his church. When the parishioners complain about the newcomers’ dirty bare feet, the pastor does what Jesus did: he washes their feet. Some members of the church leave in disgust. Others are touched by the newcomers’ sincerity.

And there are a lot of newcomers. There are joyous mass baptisms in the Pacific Ocean. Smith’s promise is a big one: “It’s not something to explain. It’s something to be experienced. What you’re seeing is a symbol of new life. Every doubt, every regret, all washed away forever.”

Much of this story is seen through the eyes of Laurie (Joel Courtney), whose book inspired the film. He comes first as an observer, bringing his movie camera. When a reporter asks if he is part of “God’s forever family,” he shrugs, “I don’t really know what a family feels like.” He finds himself drawn to the sense of community, purpose, and spirituality Smith and Frisbee are offering. He is also drawn to Cathe (Anna Grace Barlow, engagingly natural), though it takes a bit longer to figure that out. The real-life Greg Laurie is a pastor, married to Cathe.

The “contributing” parishioners say they feel uncomfortable. Smith tells them that perhaps that should be his purpose. The people he wants to comfort are the young people seeking God, not those who think they already found Him. And yet, that is just what this film does not do. Smith promises forgiveness, freedom, and acceptance, “No guilt trips. This is your home.” In other words, comfort. Yet, when Smith and Frisbee have an acrimonious split after Frisbee starts exhibiting signs of instability and grandiosity, all we learn is a brief text over the end credits that they later reconciled. There is nothing about the troubled years covered in the documentary, “Frisbee: The Life and Death of a Hippie Preacher.”

This film is capably made but superficial. It’s tricky to balance acceptance, guidance, and consequences; it is impossible to make everyone feel equally valued all the time. “Jesus Revolution” is more of a wistful wish to bring in a wave of new followers than an effort to understand what they’ll need once they’re there. To quote Jack Kornfield, from another faith tradition, “after the ecstasy comes the laundry.”

Now playing in theaters.