The Passion play has been a success for more than 40 years in the famous Montreal basilica, but the passage of time has made it seem old-fashioned, and modern audiences are growing restless. It’s time for an overhaul.

So the priest in charge hires some new actors – younger, more inventive – to stage a revised and updated version. And they make the mistake of taking their material literally.

The teachings of Christ, it has often been observed, would be radical and subversive, if anyone ever took them literally. And they would be profoundly offensive to those who build their kingdoms in this world and not in the next. The actors who rewrite the Passion in “Jesus of Montreal” create a play that is good theater and perhaps even good theology, but it is not good public relations. And although audiences respond well and the reviews are good, the church authorities are reluctant to offend the establishment by presenting such an unorthodox reading of the sacred story. So they order the play to be toned down.

But by the time they act, a curious thing has happened to the actors. They have come to believe in their play, to be shaped by the roles they play. “Jesus of Montreal” does not try to force a parallel between the Passion of Christ and the experiences of these actors. And yet certain similarities do appear, and Daniel (Lothaire Bluteau), the actor who plays Christ, discovers that his own life is taking on some of the aspects of Christ’s. By the end of the film we have arrived at a crucifixion scene that actually plays as drama, and not simply as something that has been forced into the script.

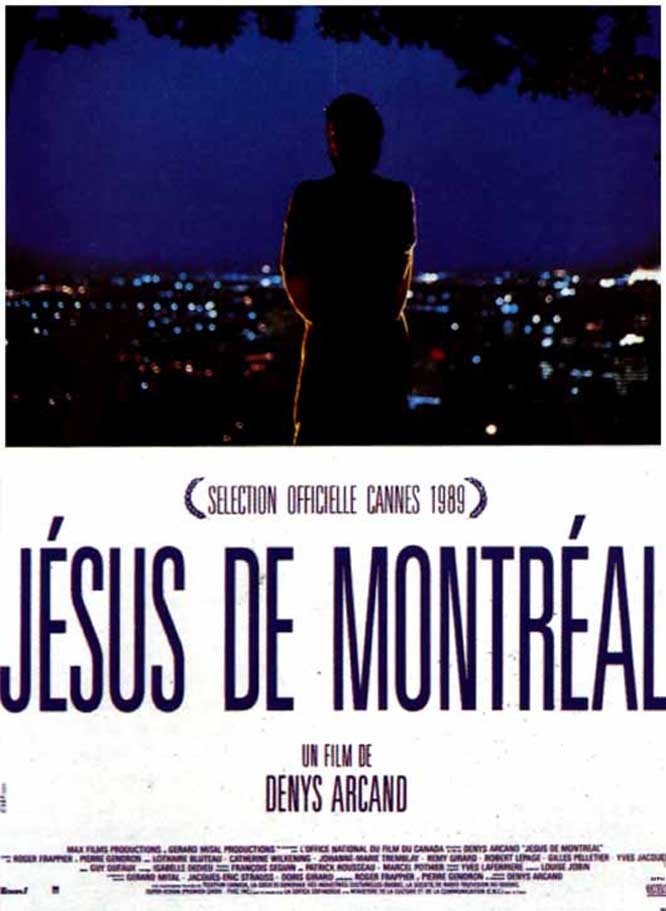

“Jesus of Montreal” was written and directed by Denys Arcand, the best of the new generation of Quebec filmmakers. His previous film was “The Decline Of The American Empire,” in which a group of Montreal intellectuals gathered to prepare a meal and talk about the meanings of their lives; it was sort of a conversational version of “The Big Chill.” This film is much more passionate, and angrier. It suggests that most establishments, and especially the church, would be rocked to their foundations by the practical application of the maxims of Christ.

Many of the scenes have obvious parallels in the New Testament. In one, an actress from the troupe appears at an audition for a TV commercial and is asked to take off her clothes – not because nudity is required in the commercial, but more because the casting director wants to exercise his power. Arriving late at the audition, Daniel, the Christ figure, shouts out to his friend to leave her clothes on. And then, when the advertising people try to have him ejected, he goes into a rage, overturning lights and cameras. It is a version, of course, of Christ and the moneylenders in the temple.

Another way in which “Jesus of Montreal” parallels the life of Christ is in the way a community grows up around its central figure.

Filled with a vision they believe in, nourished by the courage to carry on in the face of the authorities, these actors persist in presenting their play even in the face of religious and legal opposition.

It’s interesting the way Arcand makes this work as theology and drama at the same time; in a sense, “Jesus of Montreal” is a movie about the theater, not about religion.

If you go to the movie, pay close attention to Bluteau in the title role. He is considered the most powerful actor to come out of Canada in years, with his emaciated good looks and his burning intensity, and he has recently received strong reviews for his stage work in London.

Bluteau is an actor of the Mickey Rourke-Eric Roberts-James Woods school, consumed with fire, intense in his concentration, and he is just right for this role.

As for the film itself, I was surprised at how absorbed I became, even though right from the beginning I assumed I would see some kind of modern parallel of the Passion. Arcand doesn’t force the parallels, and his screenplay is not simply an updated paraphrase of the New Testament.

It’s an original and uncompromising attempt to explore what really might happen, if the spirit of Jesus were to walk among us in these timid and materialistic times.