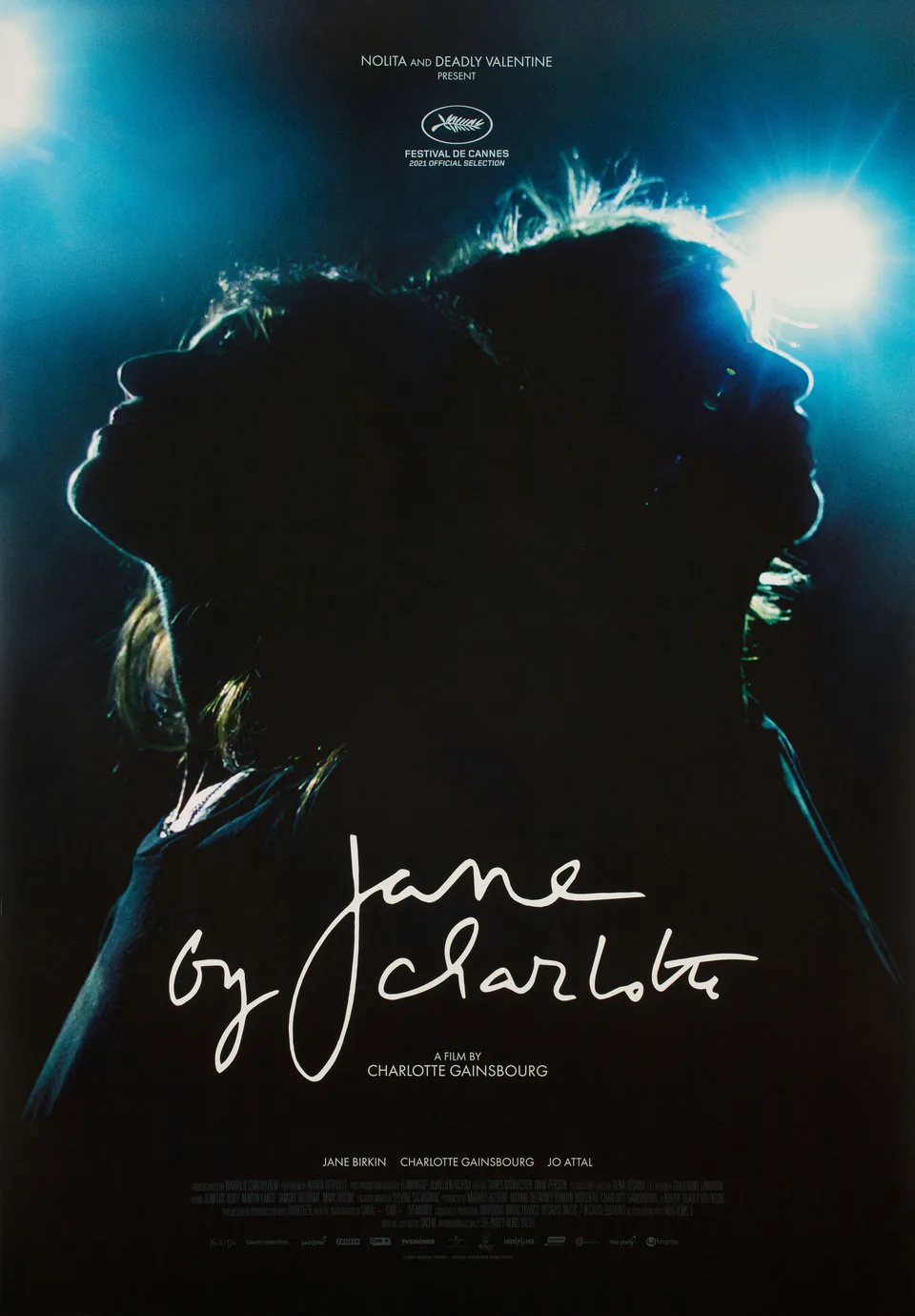

Before an orchestra tunes up to present her mother on a stage, legendary French film actor Charlotte Gainsbourg tells her legendary French film actor mother Jane Birkin that she wants to see Birkin as she hadn’t before. That notion is accompanied with wide shots of Birkin sitting; a shot that lets the beholder study. The shot suggests the way that Gainsbourg has seen Birkin before. They’ve shared home movies previously, but this documentary—meaningful in concept, but fleeting in its expression—puts them in close-up, with Gainsbourg behind the camera in her debut.

In making a film about her mother, Gainsbourg of course leads with immense feeling. She talks in her voiceover about how the project has made her more sentimental, and that becomes apparent in the way she loving photographs, interviews, films, and sits across from her mother. But the documentary does not have enough of a larger plan—Gainsbourg tells Birkin that she wants to shoot as many short sequences as possible before September, which is what we get as welcome voyeurs to their lives. They spend time at Birkin’s home in the French country, they travel to New York City for their duo musical performances; they wander a museum that Charlotte has curated about Serge Gainsbourg. In between, there are questions about Birkin’s relationships, and her thoughts about the loss of her daughter Kate, who she had with John Barry. It’s a daughters access to her mother, and their time together, but ironic that something made with such emotion can feel so cold.

Depending on one’s own relationship with Birkin and Gainsbourg as stars and their public private life and others, that might be enough. But Gainsbourg does not open the larger context, and one has to grasp at ruminations and reflections on motherhood, while they nonetheless float away scene by scene. It’s a powerful concept for a child to understand their parent face to face, but Gainsbourg does not build on it. The documentary’s ambitions remain humble, mild.

Every now and then, a more intentional scene is brought into the edit, like when Birkin and Gainsbourg lay in a white bed, dressed in white, talking about Birkin’s history with sleeping pills throughout the life events and relationships of her life. The scene is visually striking as a type of installation, but leans into the “Jane by Charlotte” ethos of being overlong and not all that poignant. In between, we watch Gainsbourg photograph Birkin from various angles, sometimes focusing on her hands. We appreciate the art, but the desired power, less so. In “Jane by Charlotte,” it is not often enough that we feel like we see what Gainsbourg sees.

Now playing in theaters.