Welles was not in Los Angeles to defend his film because he was on location in Brazil, directing an anthology film named “It’s All True,” which Nelson Rockefeller thought would cement wartime relationships between the United States and Latin America, and which almost everyone else, possibly except for Welles and his team, thought was a cockamamie project from the beginning.

“The Nelson Proj-ect,” as Welles was later sardonically to call it, would include a Mexican bullfighting sequence, a documentary about carnaval in Rio, a lot of samba dancing in Technicolor, and a black and white sequence telling the story of four poor peasants who sailed their raft more than 1,000 miles to ask the president of Brazil for help for their people.

Much of the footage for “It’s All True” had already been shot when the studio, RKO, pulled the plug on Welles’ budget and ordered him home. The movie was never released, “Ambersons” was butchered badly in his absence, and his career, which began with what many believe is the greatest film ever made, never ever quite recovered. Welles spent the rest of his life fighting a reputation as a dilettante who didn’t finish things, but the “It’s All True” fiasco was not his fault.

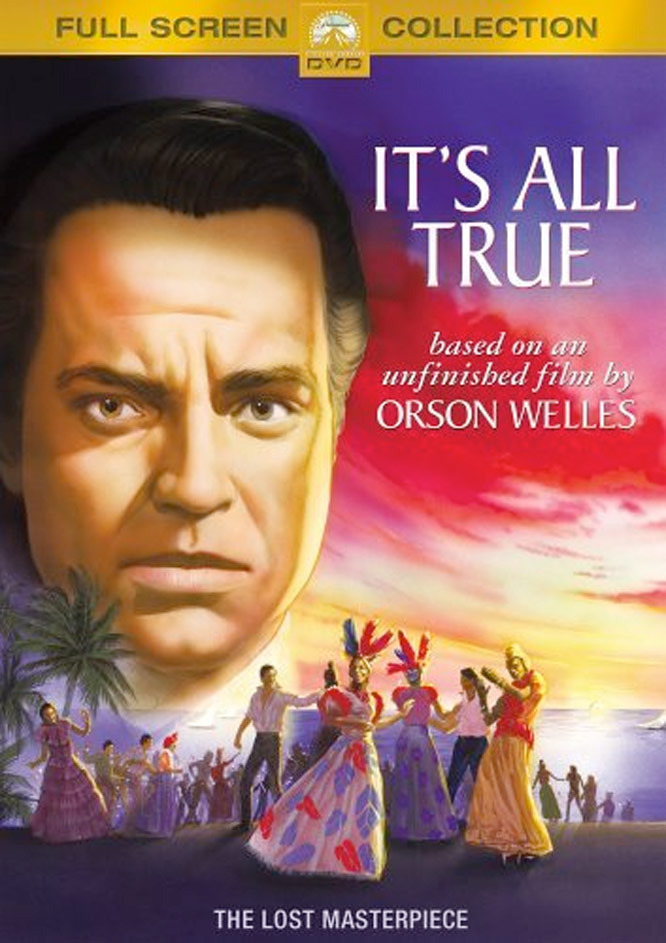

Now here is a documentary named “It’s All True” which brings together much of the surviving footage from the American adventure, and adds interviews with Welles, cinematographer Joseph Biroc, his associate Richard Wilson and others who worked on the project.

Because Welles is arguably the most magnetic and mercurial of all American directors, the film would be interesting on any grounds, but it is also impressive because of the long raft sequence, shown here in an essentially complete state.

The story of the four fishermen and their 1,650-mile journey up and down the coast of Brazil was already famous before Welles filmed it. But the filming began on a note of tragedy. While Welles was shooting the men on the raft in Rio’s Guanbara Bay, the tiny craft overturned and one of the men – their leader, known as Jacare – was lost. The same day, RKO pulled the plug, but Welles struggled on with a skeleton crew and eventually did shoot a silent black and white documentary-style story.

The footage was thought lost for years, until it surfaced in a Paramount vault. Now you can see it, like a ghost film from the past.

In its unusual camera angles it resembles some compositions Welles would use in “Macbeth” (1947) and “Othello” (1952), and in its more heroic moments it looks like something by Sergei Eisenstein. The fishermen never emerge as individuals, but their feat – sailing 1,650 miles in the open sea, without navigational aids, in a craft smaller than a bed – remains incredible.

Welles appears both young and old to describe the unmaking of “It’s All True.” In a sequence shot years ago, he leans toward the camera in a conspiratorial pose, deliberately acting; in later footage, he simply tells the old story once again. Both Welles and the filmmakers who compiled this documentary after his death insist it was Rockefeller and his friend John Hay Whitney who encouraged the South American project, although the controversial Charles Higham biography of Welles says the Brazilian minister of propaganda first dreamed up the scheme. Rockefeller embraced it, Higham says, for shady motives. (It must be said that Higham’s lurid view of Rockefeller’s secret motives does not find much support elsewhere.) What is clear is that Welles, still in his mid-20s, and heady with the success of “Kane” and the apparent success of “Ambersons,” got swept up in a wave of patriotic fervor and embarked on the South American project without really asking himself if this trip was necessary. In Brazil, with no definite script or game plan and with input from countless American and Brazilian functionaries, he seemed to improvise his way through the film. Maybe, given the money, he would have finished it. Maybe not. What remains is some dramatic quasi-documentary footage by Welles, surrounded by the poignant story of a project that went so far wrong that Welles spent four decades under its shadow.