This review ran on December 20, 2019 and is being re-run now that it is on Amazon Prime today, 4/3.

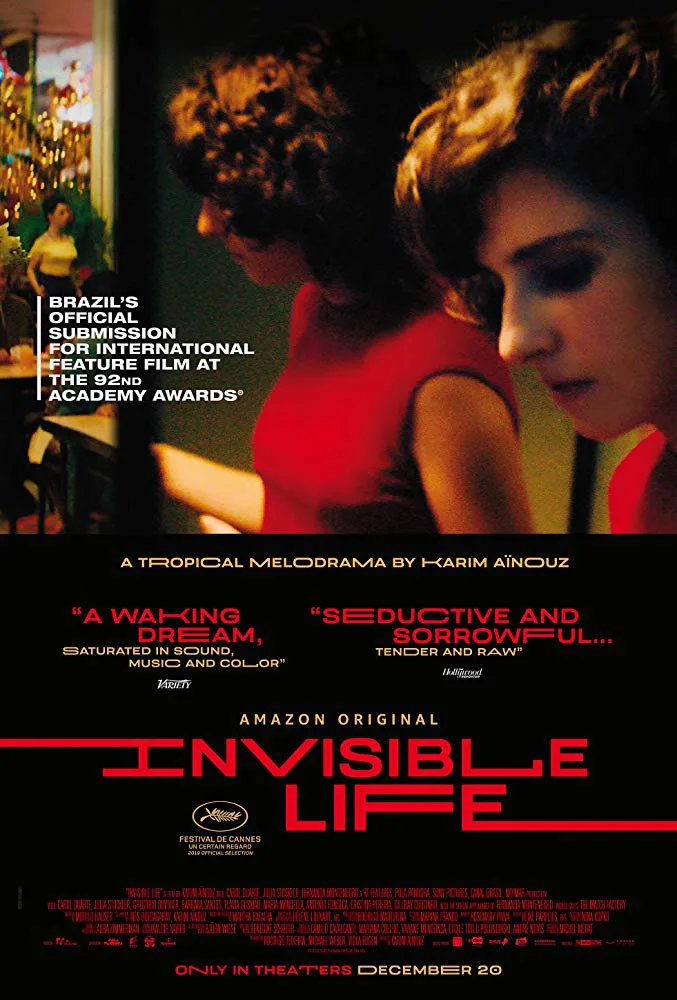

Lush melodramas are a dying breed, especially masterful ones like Karim Aïnouz’s “Invisible Life” that wear Douglas Sirkian genre conventions on their sleeve proudly and abundantly. From its very first frame, Aïnouz’s vibrant and warm-hued picture—the deserving winner of the Un Certain Regard prize at the 2019 Cannes Film Festival—envelops you within its tropical world of saturated colors and extreme sensations, to then gradually ascend to a heartrending finale, honoring the sisterly bond at its center with an openhanded serving of tears. Adapted from Martha Batalha’s novel (by Murilo Hauser, Inés Bortagaray and Aïnouz), “Invisible Life” is knowingly old-fashioned, relentlessly emotional and deeply moving in its telling of a Rio de Janeiro-set tale that starts in the 1950s and spans across decades through the life trajectory of two sisters cruelly separated in the hands of patriarchal customs.

The aforementioned young women are Eurídice and Guida of the conservative Gusmão family, played respectively by a fiercely spirited Carol Duarte and a tenacious, unconventionally strong Julia Stockler. Dissimilarly motivated they may be, but the two tight-knit, vigorous siblings still carve out a joint sanctuary for themselves, in a home that has patience for neither the sexually liberated Guida’s secret romances nor Eurídice’s ahead-of-her-time aspirations to become a concert pianist. Aïnouz quickly eases us into the sisters’ sacred haven inside and around their middle-class household. First, we meet them on a day of hiking in a sweaty, buzzing jungle where the duo briefly loses and calls for each other in echoes that explicitly foreshadow the tragedy to come. Then, we are in their shared bedroom where Eurídice reminisces about her recent sexual experience with a sailor; as we understand, one of the many playful, cozy moments between the young women that get interrupted by parents demanding their presence at dinner, in front of guests or future suitors.

The closeness of the sisters—constructed with startling finesse and economy in the story’s initial brief chapter—is an asset that comes in handy later in Aïnouz’s film, when the women find themselves on separate paths. It’s thanks to that well-realized intimacy that we long for their reunion throughout the story, and never give up hope on their behalf. The parting in question gets set in motion after Guida runs away with her lover all the way to Greece, only to come back pregnant and unmarried to a father strongly rejecting his own daughter’s return to family home. (Meanwhile, Guida’s mother seems heartbroken yet powerless to protest within the trappings of the same male-favoring oppression.) Then comes the malicious lie told by the parents to supposedly protect the Gusmão family honor—believing her parents’ word that Eurídice had left to study music in Vienna, Guida (now discarded as a shamed woman) embarks on her own destiny in a lesser corner of Rio, trying to make ends meet while raising a child with meager resources.

Profoundly observant of womanly hardships in the sentimental tradition of Latin American soaps, Aïnouz must have experienced his own share of matriarchal love and support; and even witnessed the menacing claws of toxic masculinity suffocate the female experience in conservative societal units. How else could he be this attuned to Eurídice’s ache, especially when the young woman marries an older man and has her first, painfully awkward (and even abusive) sexual encounter on her wedding night? The marital intercourse Aïnouz orchestrates in a stark bathroom alongside his brilliant cinematographer Hélène Louvart (a repeat collaborator of names like Agnès Varda and Claire Denis) manages to be defiantly bleak, non-male-gazy and unsexy all at once. In that, when the newlywed Eurídice eventually gives in to her unrefined, unsympathetic spouse, their union heartbreakingly resembles a version of date-rape.

On another side of town, Aïnouz also continues to follow Guida. Now under the wings of former prostitute Filomena (Barbara Santos) in a makeshift family, Guida works two jobs, raises her son and despite the financial and logistical challenges of her life, benefits from a relatively freer form of existence. (If you don’t count an episode where she can’t obtain travel documentation for her son without the approval of a father no longer in the picture.) Eurídice can’t possess a similar sense of autonomy nevertheless—her conservatory dreams she tirelessly works for take a backseat when she gets pregnant against her own will with no access to contraception. Worse, her protests fall on the deaf ears of her husband, who can’t grasp why playing the piano at home isn’t enough.

With a graceful handle on the passage of time and laced with yearning, resilience and occasional cadences of Bach tunes, “Invisible Life” is a sharp critique of societies that put power-tripping men in positions of authority and imprison women in their shadow. Always present as a subject matter, this theme comes into its sharpest focus during a superbly edited, devastating scene where the women miss each other in a restaurant only within a matter of moments. Still, “Invisible Life” can’t help but also exist as a hopeful celebration of female camaraderie and strength, hidden in the passages of familial letters that make it into the caring hands they were intended for way too late. It’s that optimism, that generous spirit that makes Aïnouz’s beautiful film all the more sublime.