Paul Bellamy is large, unkempt, sweet, blissfully married and very calm for a police inspector. He doesn’t solve a case so much as observe it with interest as it solves itself by the working of human nature. If you, like me, are a lover of Simenon’s Inspector Maigret, you will find his nature embodied here in the performance of Gerard Depardieu. If you are not, get your hands on a Maigret novel and thank me for the rest of your life.

As Claude Chabrol’s “Inspector Bellamy” opens, Paul is on holiday with Francoise Bellamy (Marie Bunel) who, like Madame Maigret, understands her husband profoundly and is his sounding board as a case first baffles him and then unfolds under the gentle pressure of his low-key snooping.

A man has been following them for days, and even now is creeping about in the garden. This man is named Gentil, and later will turn out to be Leullet, who Gentil killed, “sort of,” while actually killing Leprince, who was in a sense only technically a victim. All three men are played by Jacques Gamblin. This is not at all confusing, because of the ordered precision of Bellamy’s approach, and Chabrol’s.

Besides, it doesn’t matter so much who did what and to whom. As in a Simenon novel, the solution is less interesting than the people encountered along the way, and the sometimes sad lessons to be learned. “Inspector Bellamy” is only technically a murder mystery, and the critic Armond White is correct in observing, “genre is Chabrol’s MacGuffin.” After hooking the audience with the mystery, Chabrol then uses it as his avenue into the relationships between Bellamy and his wife; his loutish half-brother, Jacques (Clovis Cornillac), and two spritely local women who are mistresses, but not always the mistresses of those who claim them.

Chabrol as always shows a tenderness toward the lives of people who are exceptional only because crime touches them. He pays great attention to domestic details, and to the tone of the pillow talk between the Bellamys. He suggests that in their marriage, and perhaps in every marriage, things are not as simple as they seem. (Here he departs from Simenon; in Maigret’s marriage, I believe things are as simple as they seem.) He introduces an extra character in Jacques —who is unnecessary in terms of the murder — really, not merely “seemingly” unnecessary. And Chabrol explores the unhappy history of Paul and Jacques, involving Francoise. In their relationship, he uses the detective genre just as White says he does, as a device to involve us in another story thread.

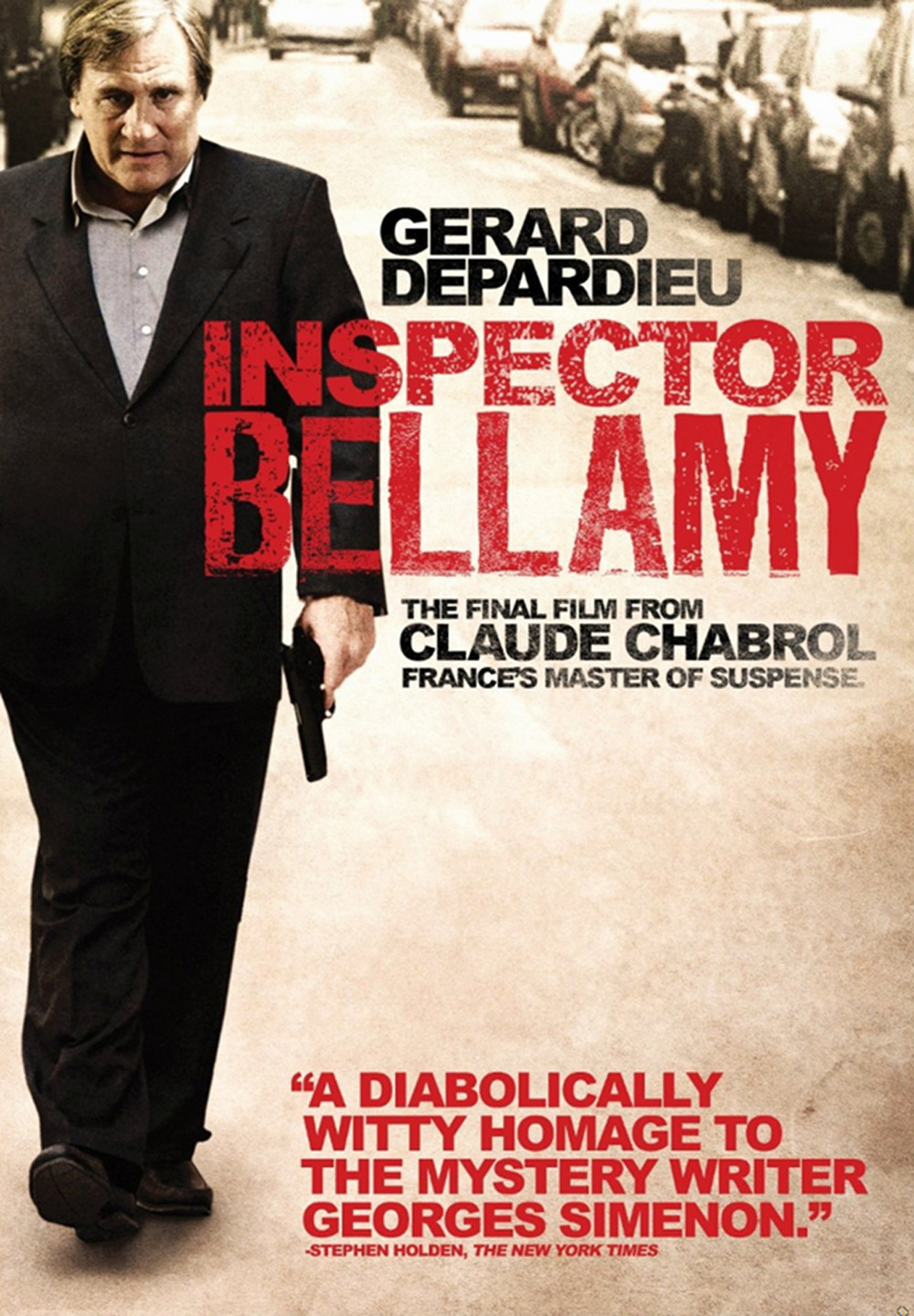

Chabrol began making films at the dawn of the New Wave, in 1958. Depardieu began in 1970. Both worked prolifically. It’s hard to believe this is the first time they worked together. Chabrol and Odile Barski wrote the screenplay especially for Depardieu, and deliberately as homage to Simenon and Maigret; now that I see Depardieu as the famous inspector, I agree, yes, he makes a convincing Maigret, although at least two dozen other actors have played him. He is bulkier than I picture Maigret, and I’ve assumed the inspector’s nose was less exceptional, but there is the inner quiet, the tranquility in the face of violence, the curiosity and acceptance of human nature.

Here is a movie about a cop and a crime in which not one shot is fired. The only person who gets slapped is Bellamy. The movie ends with wisdom and resignation, not an orgasm of hyperactive computer effects. People talk about considerable things. They speculate about motives, even their own. They are articulate. Chabrol made many such films. He died on Sept. 12, 2010, a survivor from the idealism of the New Wave, which he outlived. Which we have all outlived.