Richard Feynman, who won the Nobel Prize for physics in 1965, was one of the most interesting men our century has produced. As a very young man, he did theoretical work at Los Alamos on the project to develop an atomic bomb. In 1960, he gave a speech so famous it is known simply as “Feynman’s Talk,” in which he described a new science of nanotechnology–the manipulation of very, very small things.

Not only was it possible to write the complete contents of the Encyclopedia Britannica on the head of a needle, he said, but the contents of every book ever written could be stored in a space the size of a dust mote. (This speech helped point the way to the tiny microprocessors on silicon chips that made modern computers possible.) Near the end of his life, conducting a simple experiment with a glass of ice water, he solved the mystery of the Challenger space shuttle disaster. He died in 1988.

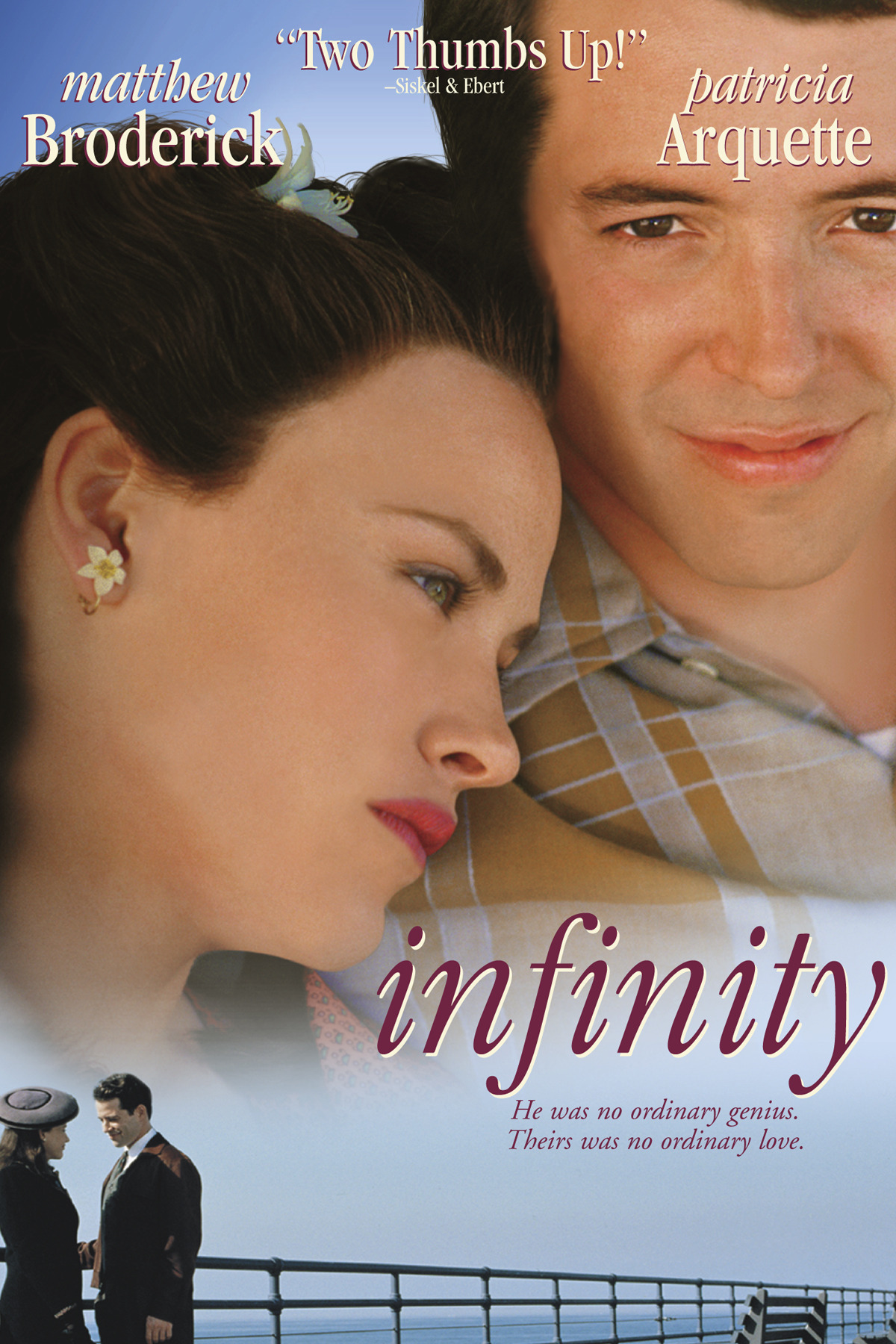

At first I was disappointed that “Infinity,” the new film based on his early years, pays relatively little attention to Feynman’s science. It follows an old tradition: Movies about great men tend to concentrate on the time when they were young and in love, rather than when they were middle-aged and doing their most important work. (It is a great relief when the subject, like Mozart, dies while still young.) “Infinity” follows Feynman (Matthew Broderick) from the late 1930s until the mid-1940s, a time during which he met and courted his first wife, Arline Greenbaum (Patricia Arquette). He was born brilliant and was not shy to admit it; on one of his first dates with Arline, he bets a Chinese merchant that he can solve problems in his head faster than the man can use his abacus.

A graduate of MIT, now studying at Princeton, Feynman long has been in love with Arline. Marriage, they thought, could wait–and would have to, because they had no money. Then two things changed all that. Feynman was offered a job in the top-secret research project at Los Alamos, and Arline became seriously ill with tuberculosis.

In those days TB was a hushed-up illness; patients went to sanitariums to recover, placing their lives on hold. In the film, Feynman and his love are not sure they have time to spare. She may die. And he knows as well as anyone that the developing war may bring untold disaster. Over his parents’ objections, they get married despite her illness. Feynman leaves for New Mexico and at the first opportunity sends for Arline, who becomes a patient in an Albuquerque hospital.

Broderick and Arquette have a sweet, unforced chemistry as the young couple, who try their best to lead normal lives in an abnormal situation (in one scene, they barbecue steaks on a grill on the front lawn of the hospital). For Feynman, almost everything is an experiment; he pounces around her hospital room, testing the limits of the human nose. (His theory: We could sniff out things a lot better if we paid more attention to the process.) The project at Los Alamos takes on a shadowy unreality as a backdrop to their married life. I vividly remember the great documentary “The Day After Trinity,” about the development of the bomb, and in the backgrounds of some shots in “Infinity,” I could guess what was happening in the real world of the Manhattan Project. But the film, directed by Broderick and written by his mother, Patricia, is more concerned with their inner landscapes.

Eventually the love story won me over. I could see that “Infinity” was not going to be about Feynman’s science but about his heart, but then the film had never promised to be anything else. Maybe the problems of these two small people didn’t amount to a hill of beans in the crazy world they were living in–but they mattered to Richard and Arline, and at the center of the story is the fact that a brilliant scientist who can figure out almost anything can’t make the slightest dent in the ultimate reality of death.

“Infinity” is a sweet story about smart people, and depends for its effect on the bittersweet knowledge that their happiness is transitory. There are moments when they seem to sense some higher power, as when they hold a picnic in a kiva–one of the dwellings hewn out of rock faces by early cliff-dwelling Indians–and others when sorrow strikes, as when Richard buries his face in Arline’s clothes to remember her powder and perfume. It is a small story, and a touching one.