Edoardo de Angelis’ “Indivisible” takes a decidedly serious approach to the story of conjoined twins, initially ruminating on the lack of freedom one might have existing next to someone else for their entire lives. Instead of the freak show angle taken by the Farrelly brothers comedy “Stuck on You,” perhaps the biggest name yet in conjoined twin cinema, “Indivisible” ponders, to a limited extent, what would happen to such siblings in a world that values celebrity, religion and sex to selfish ends.

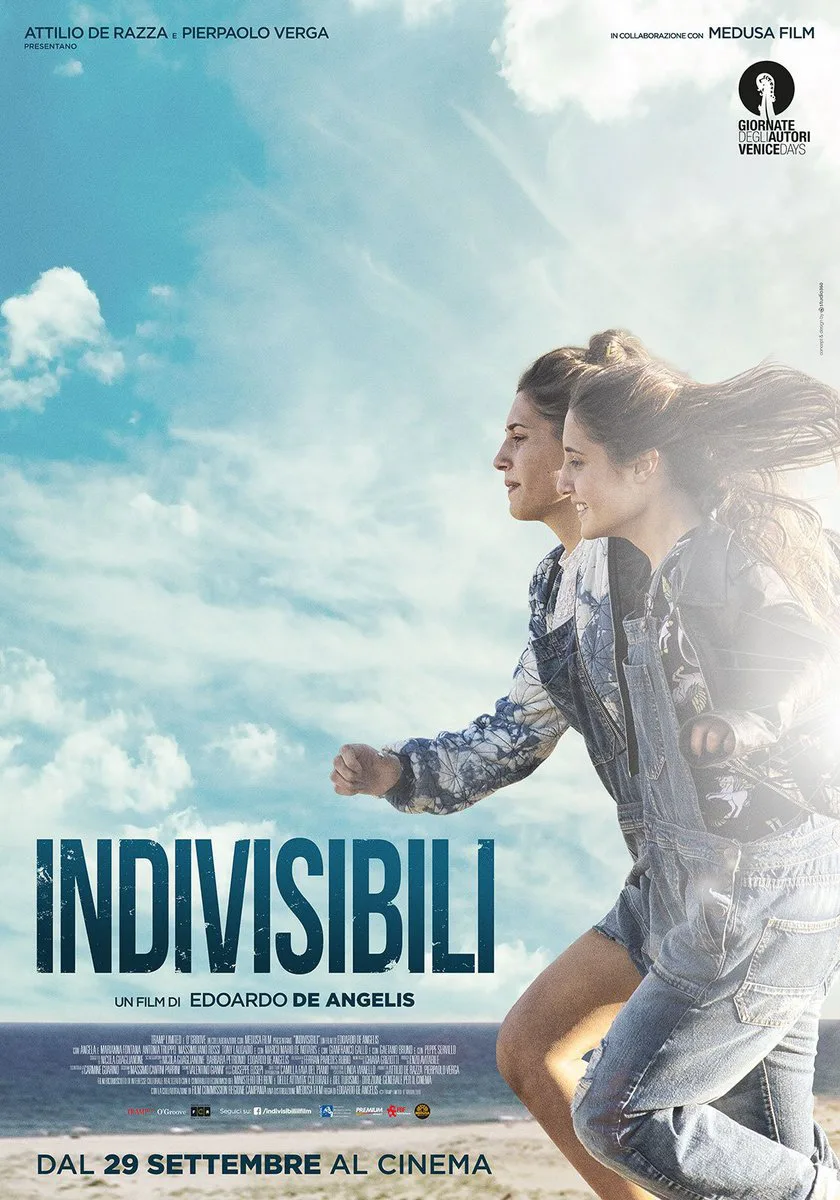

Angela Fontana and Marianna Fontana play twins Viola and Daisy, respectively, who are conjoined at the hip. They do everything together, of course, their personalities blending into one in the process. The film finds them around the age of 18, on the fringe of becoming legal adults. Not too long into “Indivisible,” they are presented with information by a doctor that they could be separated and survive, and perhaps should have been at birth. It causes tension between the two, as Daisy wants the surgery to be her own person whereas Viola does not. But together they decide to run away from the many people, especially the men, who have tried to commodify their phenomenon.

For starters, their egotistical father Peppe (Massimiliano Rossi) and defeated mother Titti (Antonia Truppo) have made them into singers who are carted around their working-class community. In a bizarre sequence in the beginning, they are shown working a first communion, crooning a song written by Peppe called “Indivisible,” both a bland ode to love and testament to the type of sentencing their family business has placed on them. In a nice touch that shows how much the same they are, and how cheap of a songwriter he is, they never harmonize, flatly singing the same notes.

There are other local men with more malicious intentions: a local priest (Gianfranco Gallo) wants to turn them into walking angels of some sort, ready to build a church in their name with parishioners set to worship. Meanwhile, a wealthy man named Marco Ferrari (Gaetano Bruno) promises the twins he could make them big international stars, while having a fetish for their handicap, his eye on Daisy in particular. Initially, these men are interesting as showing different ways that the twins are being objectified by different institutions. But the script fails to make them more than just symbols of greed and inhumanity, rendering them one-dimensional irregardless of the complicated worlds they can represent. When Daisy and Viola try to break free, their following encounters with these forces have the same stage-by-stage villainy of different bosses in a video game.

While the script has a problem sharing why it was excited to place conjoined twins in such a predicament, the Fontana sisters boast a special emotional eloquence. They are able to sell the profound love and anguish they must experience together, keeping many scenes afloat by acting off of each other face to face and with vivid, juxtaposing emotions. The movie doesn’t give them enough personality together or as individual brains, and instead makes them human beings by the main conflict of who believes in the operation and who does not. But the Fontana sisters are able to create tension within their situation, as two souls that hardly know what it’s like to be think for themselves. Their scenes alone as they try desperately convince the other of what to do, while looking right at each other, are always great.

De Angelis’ filmmaking leans into the straight-face tone with its numerous composed takes that run long and often around a crowded interior, suggesting a determination to show instead of articulate. Further, there are even images of giant Jesus statues and general excess, which recall a touch of how Fellini addressed such indulgences in “La Dolce Vita,” contextualizing the light fantasy of a grounded situation as his films so easily did. In the case of “Indivisible,” however, using some of those vibes feels to be more of just a reference, not a blessing.

But this capable filmmaking and self-assured tone aren’t very standout ideas for a movie that struggles to be as unique as its pitch. At its best, “Indivisible” provides nonpareil dramatic sensations, which especially carries some mileage for any viewer who thinks that all of storytelling is a rotating list of similar feelings. You’ve never quite felt what it’s like to hope that conjoined twins can tread water in an open sea, among a few intense examples, but “Indivisible” has that, emboldened especially by its lead performances. It’s the followthrough that provides very little that’s new to think about, as delivered by De Angelis with heavy hands.