In a land where the people are narrow and suspicious, where do they draw the line between madness and sweetness? Between those who are unable to conform to society’s norm and those who simply choose not to, because their dreamy private world is more alluring? That is one of the many questions asked, and not exactly answered, in Bill Forsyth’s “Housekeeping,” which is one of the strangest and best films of the year.

The movie, set some 30 or 40 years ago in the Pacific Northwest, tells the story of two young girls who are taken on a sudden and puzzling motor trip by their mother to visit a relative. Soon after they arrive, their mother commits suicide and the girls are left to be raised by elderly relatives. A few years later, their mother’s sister, their Aunt Sylvie, arrives to look after them.

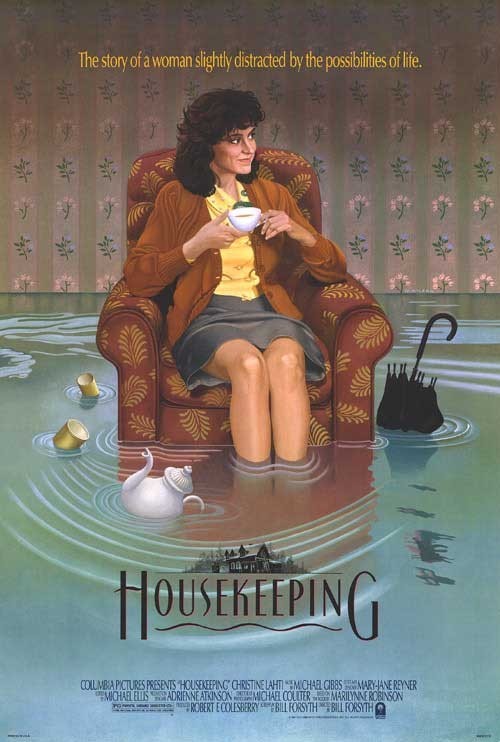

Sylvie, who is played by Christine Lahti as a mixture of bemusement and wry reflection, is not an ordinary person. She likes to sit in the dusk so much that she never turns the lights on. She likes to go for long, meandering walks. She collects enormous piles of newspapers and hundreds of tin cans – carefully washing off their labels and then polishing them and arranging them in gleaming pyramids.

She is nice to everyone and generally seems cheerful, but there is an enchantment about her that some people find suspicious.

Indeed, even her two young nieces are divided. One finds her “funny,” and the other loves her. Eventually the two sisters will take separate paths in life because they differ about Sylvie. At first, when they are younger, she simply represents reality to them. As they grow older and begin to attend high school, however, one of the girls wants to be “popular” and resents having a weird aunt at home, while the other girl draws herself into Sylvie’s dream.

The townspeople are not evil, merely conventional and “concerned.” Parties of church ladies visit to see if they can “help.” The sheriff eventually gets involved. But “Housekeeping” is not a realistic movie, not one of those disease-of-the-week docudramas with a tidy solution. It is funnier, more offbeat, and too enchanting to ever qualify on those terms.

Forsyth, the writer and director, has made all of his previous films in Scotland (they make a list of whimsical, completely original comedies: “Gregory’s Girl,” “Local Hero,” “Comfort and Joy,” “That Sinking Feeling”). For his first North American production, he began with a novel by Marilynne Robinson that embodies some of his own notions, such as that certain people grow so amused by their own conceits that they cannot be bothered to pay lip service to yours.

In Lahti, he has found the right actress to embody this idea.

Although she has been excellent in a number of realistic roles (she was Gary Gilmore’s sister in “The Executioner’s Song” and Goldie Hawn’s best friend in “Swing Shift”), there is something resolutely private about her, a sort of secret smile that is just right for Sylvie. The role requires her to find a delicate line; she must not seem too mad or willful, or the whole charm of the story will be lost. And although there are times when she seems to be indifferent to her nieces, she never seems not to love them.

Forsyth has surrounded that love with some extraordinary images, which help to create the magical feeling of the film. The action takes place in a house near a lake that is crossed by a majestic, forbidding railroad bridge. It is a local legend that one night decades ago, a passenger train slipped ever so lazily off the line and plunged down, down, into the icy waters of the frozen lake. The notion of the passengers in their warm, well-lit carriages, plunging down to their final destination, is one that Forsyth somehow turns from a tragedy into a notion of doomed beauty. And the bridge becomes important at several moments in the film, especially the last one.

The location where the film was shot (British Columbia) and the production design by Adrienne Atkinson are also evocative. It is important that the action takes place in a small, isolated community, in a place cut off from the world where whimsies can flourish and private notions can survive. At the end of the film, I was quietly astonished. I had seen a film that could perhaps be described as being about a madwoman, but I had seen a character who seemed closer to a mystic, or a saint.