But what is a normal house, anyway? In “The Fast Runner,” we see a civilization that lives in igloos. In “Taiga,” we visit the yurt dwellers of Outer Mongolia. Their homes are at least functional, economical and organic to the surrounding landscape. It’s possible that the most bizarre homestyles on Earth are those proposed by Martha Stewart, which cater to the neuroses of women with paralyzing insecurity. What woman with a secure self-image could possibly dream of making those table decorations? The five subjects of “Home Movie” at least know exactly why they live where they do and as they do, and they do not require our permission or approval. There is Bill Tregle, whose Louisiana houseboat is handy for his occupation of trapping, selling and exhibiting alligators. He catches his dinner from a line tossed from the deck, has electric lights, a microwave and a TV powered by generator, pays no taxes, moves on when he feels like it, and has decorated his interior with the treasures of a lifetime.

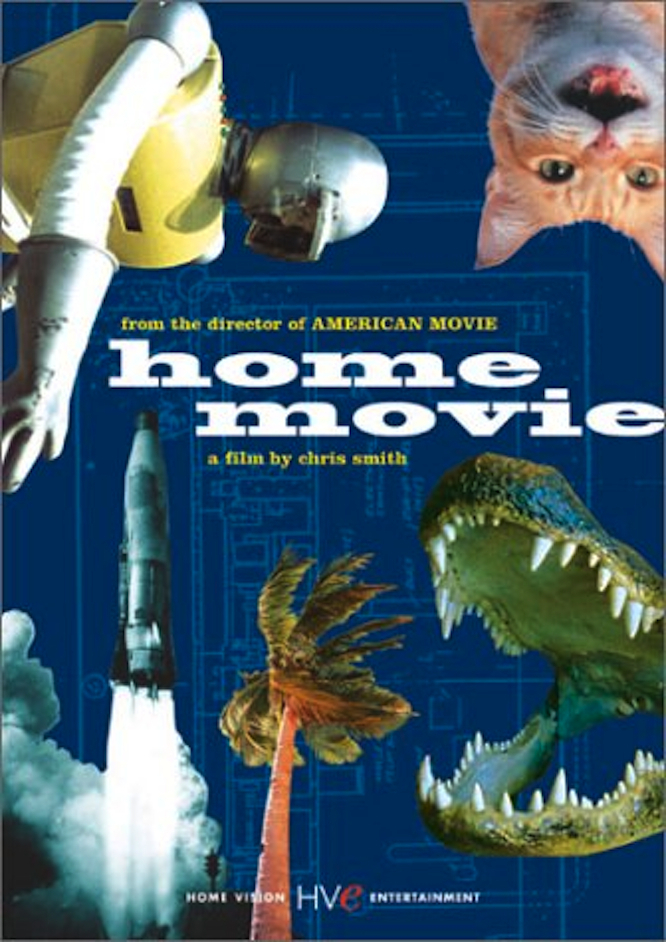

Or consider the Pedans, Ed and Diana, who live in a converted missile silo. The concrete walls are so thick that they can have “tornado parties,” and there’s an easy commute down a buried tunnel from the living space to the work space. True, they had to build a greenhouse on the surface to get some sun or watch the rain, because otherwise, Diana observes, it’s too easy to stay underground for days or weeks at a time. Their living room is the silo’s former launch center–interesting karma.

Linda Beech speaks little Japanese, yet once starred on a Japanese soap opera. Now she lives in the Hawaiian rain forest, in a tree house equipped with all the comforts of home. To be sure, family photos tend toward mildew, but think of the compensations, such as her own waterfall, which provides hydroelectric power for electricity, and also provides her favorite meditation spot, on a carefully positioned “water-watching rock.” She can’t imagine anyone trying to live without their own waterfall.

Bob Walker and Francis Mooney have dozens of cats. They’ve renovated the inside of their house with perches, walkways and tunnels, some of them linking rooms, others ending in hidey-holes. They speculate about how much less their house is worth today than when they purchased it, but they’re serene: They seem to live in a mutual daze of cat-loving. The cats seem happy, too.

Ben Skora lives in a suburb of Chicago. His house is an inventor’s hallucination. Everything is automatic: The doors, which open like pinwheels, the toilets, the lights, the furniture. The hardest task, living in his house, must be to remember where all the switches are, and what they govern. He also has a remote-controlled robot that is a hit at shopping malls. The robot will bring him a can of pop, which is nice, although the viewer may reflect that it is easier to get a can out of the refrigerator than build a robot to do it for you. Skora’s great masterwork is a ski jump that swoops down from his roof.

Are these people nuts? Who are we to say? I know people whose lives are lived in basement rec rooms. Upstairs they have a living room with the lamps and sofas still protected with the plastic covers from the furniture store. What is the purpose of this room? To be a Living Room Museum? What event will be earth-shaking enough to require the removal of the covers? Do they hope their furniture will appreciate in value? There is no philosophy, so far as I can tell, behind Chris Smith’s film. He simply celebrates the universal desire to fashion our homes for our needs and desires. Smith’s previous doc was the great “American Movie,” about the Wisconsin man who wanted to make horror movies, and did, despite all obstacles. Perhaps the message is the same: If it makes you happy and allows you to express your yearnings and dreams, who are we to enforce the rules of middle-class conformity?

Note: “Home Movie,” 65 minutes long, had been linked with “Heavy Metal Parking Lot,” a time capsule doc shot in the parking lot outside a Judas Priest concert in 1986. The band’s fans, zonked on strange substances, seem to have no homes at all, and to live entirely in the now, as stoned worshippers at the shrine of their own bewilderment.