“Himalaya” tells the story of a village, which since time immemorial, has engaged in a winter trek to bring salt to its people and send out goods to be traded. The journeys are conducted by yak caravans. For many years the old chief, Tinle, led the treks, but he retired in favor of his son. Now his son is dead, his body brought back to the village by Karma, who wants to take his place at the head of the caravans.

Tinle (Thinlen Lhondup) is not so sure. He is half-convinced Karma (Gurgon Kyap) has something to do with the death of the son. And he believes the position of honor should remain within his own family. He goes to visit another son, who is a monk in a Buddhist monastery. This son wants to stay where he is. So Tinle defiantly says he will come out of retirement and lead the next caravan. And Karma says, no, he will lead it instead.

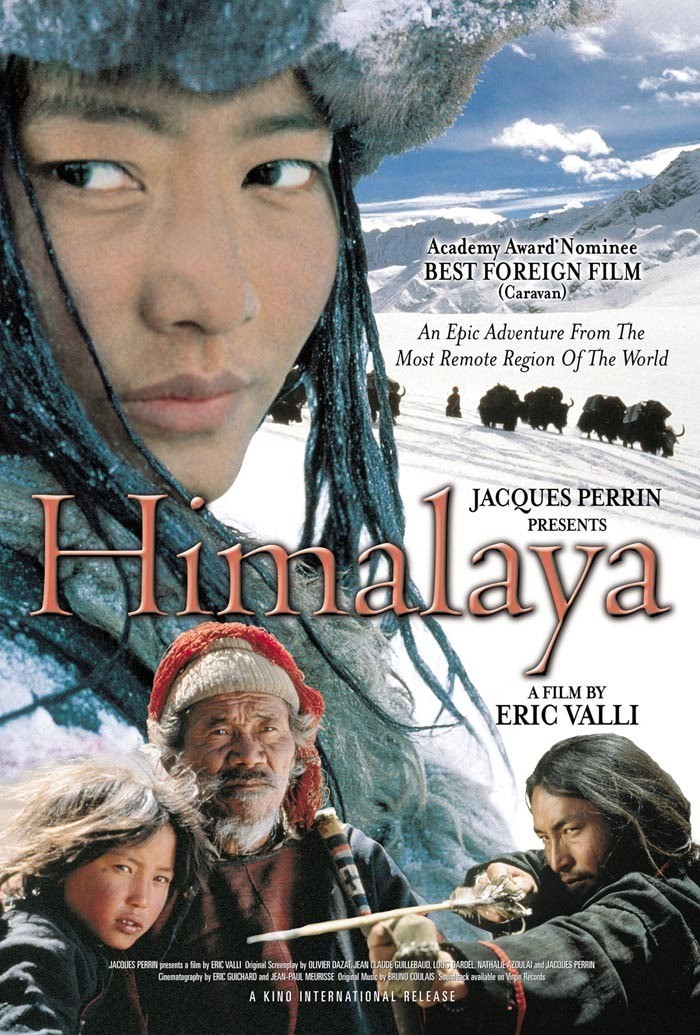

So begins “Himalaya,” a film of unusual visual beauty and enormous intrinsic interest. Set in the Dolpo area of Nepal, it has been directed by Eric Valli, a photographer who has lived in Nepal for years, filmed it for National Geographic, and made documentaries about it. Now in this fiction film he uses conflict to build his story, but it’s clear the narrative is mostly an excuse; this movie is not so much about what its characters do, as about who they are.

It is astonishing to think that lives like this are still possible in the 21st century. We are less surprised when we see such treks reflecting modern realities–as in “A Time for Drunken Horses” (2000), about the Kurdish people of Iran, who use mule caravans to transport contraband truck tires into Iraq. We suspect that the story of “Himalaya” re-creates a time that has now ended, but no: Such caravans still exist, and were the subject of “The Saltmen of Tibet,” a 1997 documentary by Ulrike Koch.

Much of the film is simply pictorial, as Karma and Tinle make rival journeys, and Tinle ominously squints at the clear sky and foresees snow. There is one passage of pure suspense, as part of a narrow mountain path slips away, and the yaks and their masters have to traverse a dangerous stretch; we are reminded of similar situations involving trucks in “The Wages of Fear” and “Sorcerer.” The actors are not experienced and sometimes simply seem to be playing men very much like themselves, but we are not much concerned with subtle drama here. The real movie takes place in our minds, as we think about these people who share the planet with us right now, and yet lead unimaginably different lives. Would it be a trial or a blessing to be a member of a community like this? That would depend, I imagine, on whether your view of the world has expanded to encompass more than villages and salt journeys. There must be something deeply satisfying about knowing your place in an ancient social structure and fitting into it seamlessly. So I thought as I watched this film, although it did not make me want to lead a yak caravan.