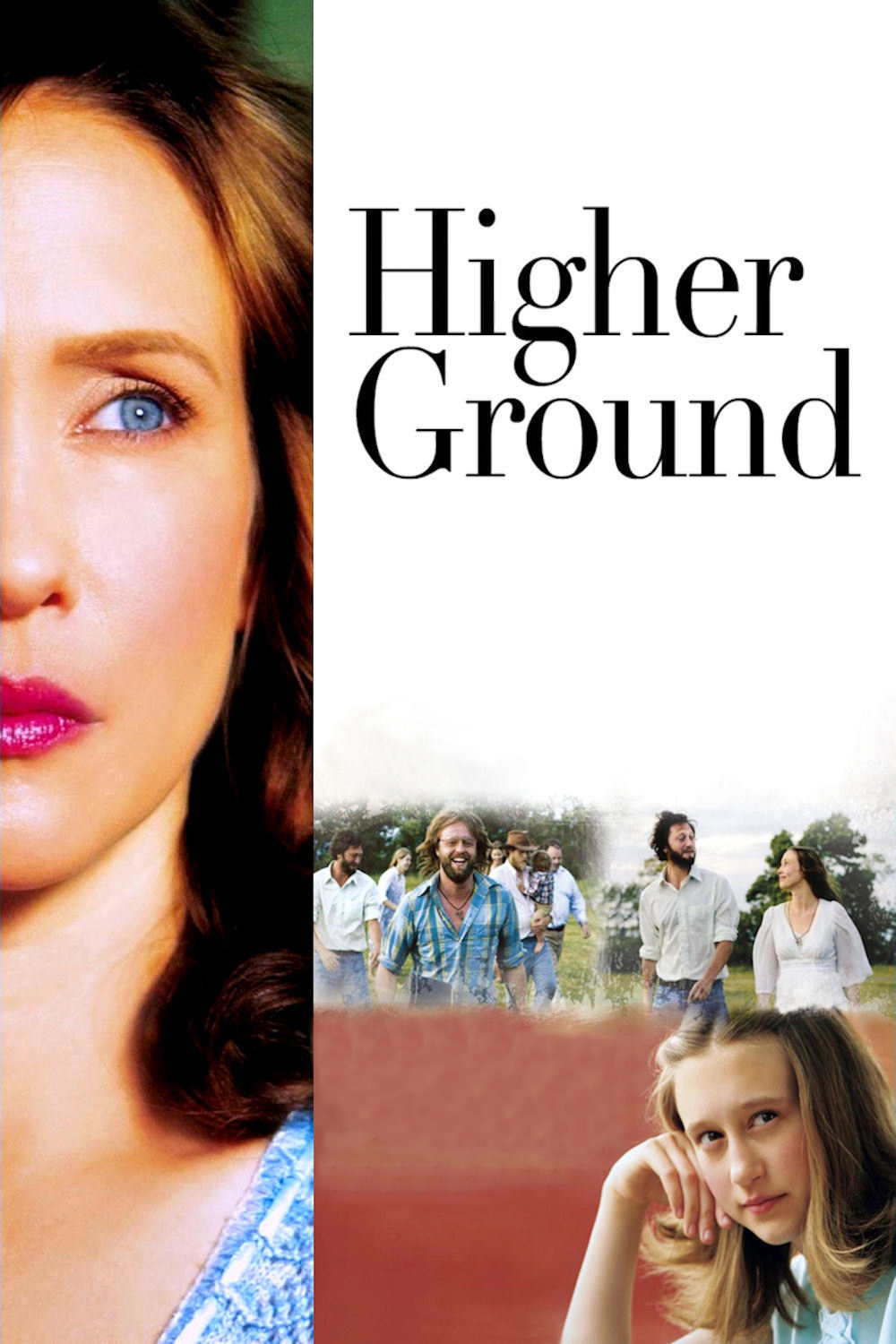

Vera Farmiga‘s “Higher Ground” is the life story of a woman who grows into, and out of, Christianity. It values her at every stage of that process. It never says she is making the right or wrong decision, only that what she does seems necessary at the time she does it. In a world where believers and agnostics are polarized and hold simplified ideas about each other, it takes a step back and sees faith as a series of choices that should be freely made.

The woman’s name is Corinne. We see her as a child, a teenager around 20 and an adult around 40. As a child, she invites Jesus into her life in a conventional mainstream Protestant sort of way. Later, she is born again, with full immersion and all the rest of it, after she and her husband credit God for saving them and their child from tragedy. Later still, she finds her evangelical congregation enforcing uncomfortable conformity upon her.

I would like to say “Higher Ground,” which marks Farmiga’s directorial debut, never steps wrong in following this process, but it does. Sometimes it slips too easily into satire, but at least it’s nuanced satire based on true believers who are basically nice and good people. There are no heavy-handed portraits of holy rollers here, just people whose view of the world is narrow. There are also no outsize sinners, just some gentle singer-songwriters who are too fond of pot and whose lyrics are parades of cliches.

Corinne is played as a girl by McKenzie Turner, as an adult by Vera Farmiga and as a teenager by Farmiga’s sister, Taissa. At all of these stages in life, the character’s face reflects awareness and intelligence, along with an inbred independence that makes her a little reluctant to go along with the crowd. At the discussions held by her prayer group, we can see her drawing a line between those who are thoughtful and those who are passive conformists. Corinne reads widely. She thinks about the Scriptures. She has opinions. She doesn’t respond well when an older woman advises her that when she speaks out, it sounds too much like preaching. God forbid a woman should have an opinion.

Yet the preachers she comes into contact with are not bad men. The film carefully avoids stereotyping them. It’s just that as she grows older, her congregation becomes a group where the others feel more included than she can. They accept. Even the men consider male dominance a duty, not a pleasure.

Corinne has a best friend, Annika (Dagmara Dominczyk), she confides in. They share thoughts about sex and other things. (Farmiga might have been wise, however, to avoid the easy laugh when each woman draws her husband’s penis. There is a statement to be made, but there must be a more subtle way to make it.)

Unhappiness strikes the group. I will not supply details. I observe, however, that a person who suffers great misfortune is unlikely to be comforted by the assurance that God’s will has been done. (In the case of my own misfortune, I prefer to think that God’s will had nothing to do with it. People who tell me it did are singularly tactless.)

Ask yourself during the film where you think it takes place — which American state? I looked up the locations on IMDb and was surprised. Its location doesn’t fit regional stereotypes. Nor do its characters. These are decent people, trying to do the right thing, and Corinne is a decent person who believes she must decide on the right thing for herself. When others inform her what that is, why are they rarely eager to have her input?

Vera Farmiga is such a warm actress. I don’t know if she could play cruel. John Hawkes, who plays her alcoholic father, can play cruel — but not in a physically violent way. His is the kind of cruelty that shows a child her father is weak and pitiful, and doesn’t deserve her respect. Perhaps that’s how she began to doubt at an early age the paternalism of her social group.

We see the seeds of imagination growing through her reading. People in books sometimes do things we can understand because we have come to know those people. Non-readers are likely to think they know what people should do because — well, they just should, that’s all. You can read this in a book: “The unexamined life is not worth living.”