Taken from farm to fable, the domesticated animals in “Gunda” star not as commodified flesh for human consumption but autonomous entities with inner lives.

The latest medium-pushing documentary from Russian director Viktor Kossakovsky is bare in its aesthetic dogma—there’s no music, no title cards, and no people in sight—and flawless with its observational truth. “Gunda” dispenses with all explanations and emotional scheming tactics for a thoroughly pictorial experience. This non-fiction rarity’s only soundtrack features an ambience choir of birds chirping and bugs buzzing.

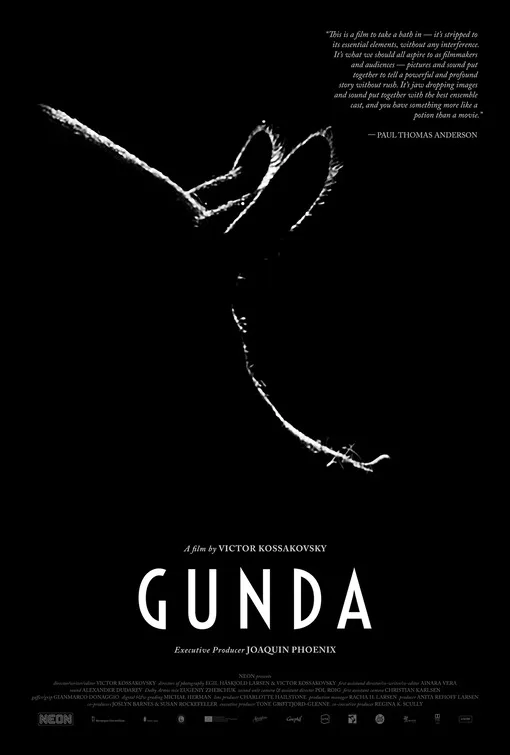

Gunda, an expressive female pig, has just given birth to a litter of impossibly adorable piglets at a Norwegian farmstead. Their high-pitch squeals, as they all fight to feed at once, announce their first bonding session with mom and each other. From the moment we are invited into the hay-laden abode, our visual contact with her and her young is always up-close. Shot with natural light and a chiaroscuro sensibility, the black-and-white frames play with shadows and silhouettes.

With the camera close to the ground and moving swiftly about the open spaces, Kossakovsky and his co-cinematographer Egil Haaskjold Larsen prioritize the animals’ vantage point. Their visual language forces the viewer to experience the world at their eye level and not from a position of dominance. There’s a miraculous blend of craft and implicit cooperation in the astounding close proximity with which they immortalized all their non-verbal subjects—including an audacious one-legged chicken.

As the small flock of chickens survey a terrain steep in vegetation they appear to be explorers in a newfound land or astronauts on a foreign planet entering the unknown. There’s a sense of discovery in the way the hesitant winged friends roam around for what seems to be their first time out of a cage. Kossakovsky lets us into their secret lives; we are guests who get to wonder in their engagement with a freedom so often denied to them.

On the rare occasion of a wide shot, we witness Gunda’s domain or that of the supporting cast. This is of special relevance in an epic scene of cattle running without restraint, or as we see the energetic, juvenile hogs chasing after their mother. Time has passed and they are much bigger but just as playful. Each segment runs its course leisurely, substituting a zoology research with a reflective study.

Kossakovsky begets meaningful character development, at once disarming and unvarnished. It’s in the way the cows stare straight into the camera or how they help one another swat insects away, in how Gunda mothers her brood or placidly lounges in mud, or in how an angelical piglet bathed in the warm morning light curiously steps into the outdoors. “Gunda” operates with the spiritual grandeur of a Terrence Malick film and an underlying, non-militant plea to rethink our relationship with animals we have dismissed as subservient and only valuable in the measure that they serve as our food.

Kossakovsky cares deeply for the beings on the other side of the lens, and nurtures our sense of cross-species empathy by highlighting the oft-ignored complexity in their existences. There’s no Animal Planet-like voyeurism of mating rituals or brutal examples of Darwinism, likewise there is no effort to forcefully anthropomorphize them how a movie like “Babe” (with voices and fantastical story arcs) does to convince us of their similarities to us. Instead, he proves that many of the qualities we tend to attribute solely to the human condition are in fact found in other inhabitants of the planet.

As is the case in all forms of creative work, there’s no escaping a degree of bias from the artist’s own belief system. Yet, even if we are aware that a fellow human is arranging what’s on screen and the meaning we derive from it, his ruling principles speak loudly with a purity of mission: the director wants the focus to be on the voiceless and their right to live. Nowhere is the potency of Kossakovsky’s committed vision more evident than in the final sequence when a metal monster blindsides Gunda and in turn guts us via our recognition of her despair. Such an agonizing moment of unequivocal emotion wrecks any doubts one might still have about her real pain, and renders “Gunda” a cinematic triumph of porcine poetry.

In theaters tomorrow, April 16th.