When you’re angry with the world and yourself to the same degree, you’re running in place. It takes a great deal of energy. It can be exhausting. You lash out at people. You’re hard on yourself. It all takes place in your head. After a time people give up on you. They think you don’t give a damn and don’t care about yourself. If they only knew.

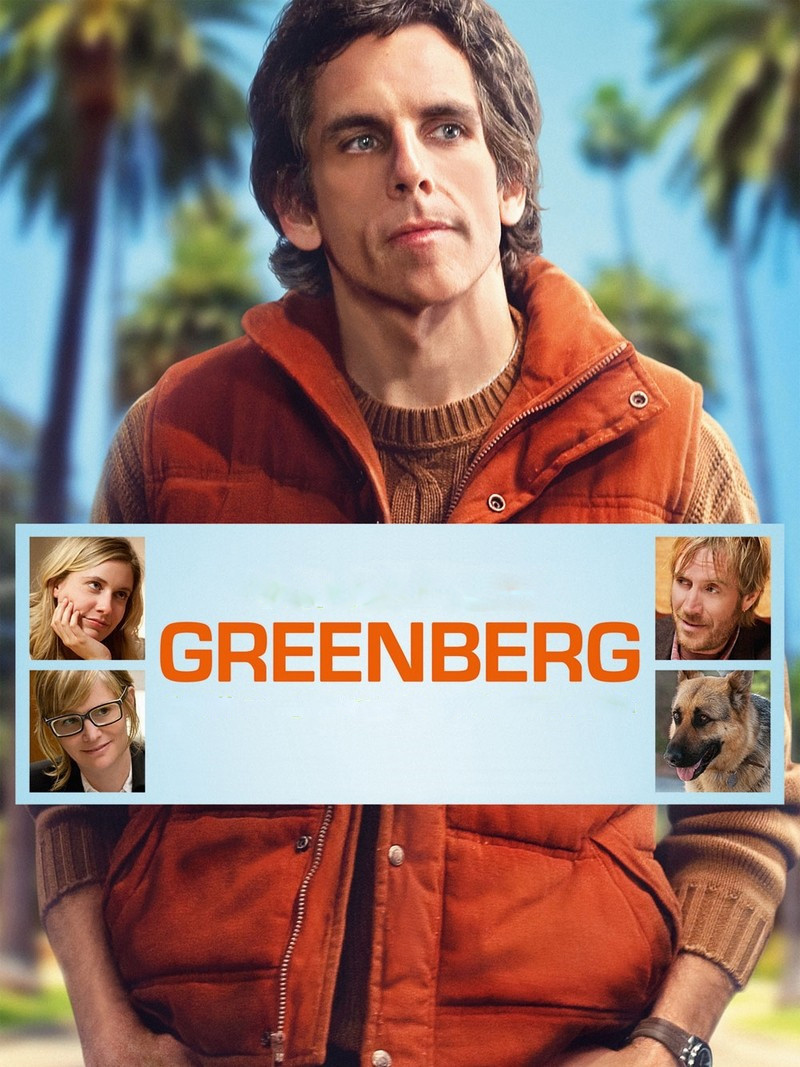

That’s Roger Greenberg. I never knew who Ben Stiller was born to play, but now I do. I don’t mean he is Greenberg, but that he makes him a convincing person and not a caricature. The hero of Noah Baumbach‘s new film was once, years ago, part of a rock band on the brink of a breakthrough. He walked away from it, stranding his band- mates, and never explained why. He fled Los Angeles and became a carpenter in New York.

He’s been struggling. There has been some sort of vague period in an institution. Now he’s returned to L.A. to house-sit his brother’s big home and look after the dog. He glares out of the windows like old man Fredricksen in “Up.” He can live alone no more successfully than with others. He calls Florence Marr (Greta Gerwig), his brother’s family assistant, who knows where everything is and how everything works. And the dog knows her.

Florence is someone we know. A bright, pleasant recent college graduate for whom the job market, as they say, has no use. We see her interacting with the family of Greenberg’s brother; she does all the planning for them she should be doing for herself. In a more conventional movie, Florence would be the love interest, and Greenberg would be fated to marry her. But Florence isn’t looking for a man. She just broke up. “I don’t want to go from just having sex to sex to sex,” she says. “Who’s the third ‘sex’?” asks Greenberg. “You.”

I have a weakness for actresses like Greta Gerwig. She looks reasonable and approachable. Some actresses are all edges and polish. This one, you could look up and see her walking dreamily through a bookstore, possibly with a Penguin Classic already in her hand. Greenberg treats her badly. He has no notion of his effect on people. When they end up having sex, and they do, it’s like their right hands don’t know what heir left hands are doing.

Noah Baumbach made the inspired “The Squid and the Whale” (2005), about a formidably articulate family torn apart by a divorce. Both parents were at fault to various degrees, and both sons could have done more in their own way to help the situation. Everyone obsessed on their grievances. Greenberg takes this a step further: He obsesses on the grievances against him.

He has a reunion with a former bandmate, Ivan (Rhys Ifans), a calm Brit, troubled by a trial separation, happy enough to see Greenberg and help him if he can. But Ivan is troubled that Greenberg still doesn’t get it, doesn’t understand how he crushed the dreams of his bandmates. Then there’s Beth (Jennifer Jason Leigh), who Greenberg once loved and was loved by. She has moved on in her life. She has a family. Does he recognize the look a woman gets in her eyes when she’s thinking how that just would have never, ever, worked out? Does he have enough self-knowledge to see how impossible he is?

The important relationship is the one between Greenberg and Florence. We look upon her and see wholesome health and abundant energy. She’s happy when she has a purpose. She wishes she had a direction in life but can be happy enough in the moment. It’s as if when Greenberg moves a little in the direction of happiness, it gets jealous because that draws attention away from his miserable uniqueness. People driven to be constantly unique can be a real pain in the ass.

This is an intriguing film, shifting directions, considering Greenberg’s impossibility in one light and then another. If he’s stuck like this at 40, is he stuck for good? What Ben Stiller does with the role is fascinating. We can’t stand Greenberg. But we begin to care about him. Without ever overtly evoking sympathy, Stiller inspires identification. You don’t have to like the hero of a movie. But you have to understand him — better than he does himself, in some cases.