Milos Forman’s “Goya’s Ghosts” is an extraordinarily beautiful film that plays almost like an excuse to generate its images. Like the Goya prints being examined by the good fathers of the Inquisition in the opening scene, the images stand on their own, resisting the pull toward narrative, yet adding up to a portrait of grotesque people debased by their society. The priests lament Goya’s negative portrait of Spain, which shows remarkable prescience on their part, since they’re condemning in 1772 prints that were not created by the painter until 1799.

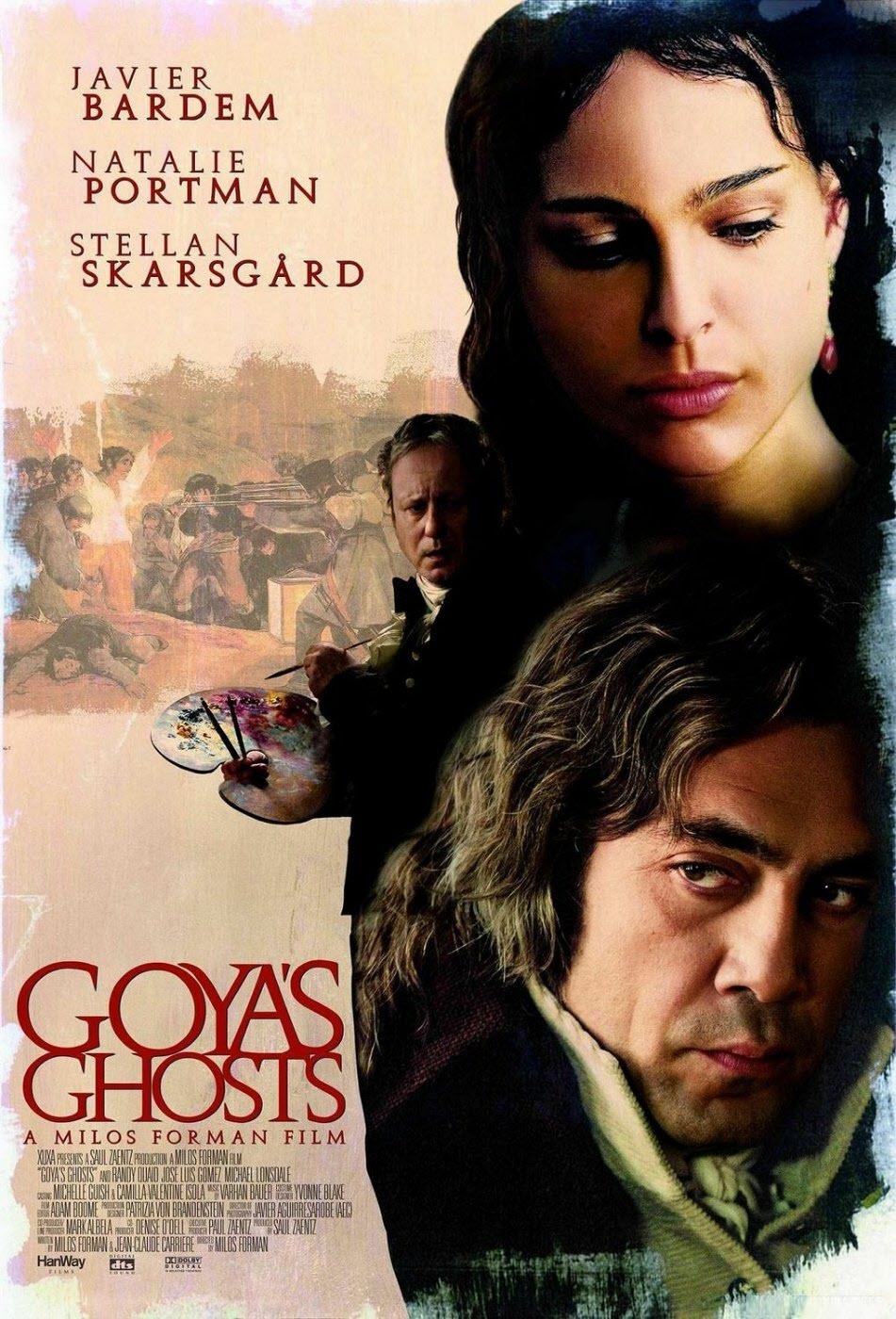

In fiction, fooling around with historical accuracy is allowed, and “Goya’s Ghosts” indulges itself. Many of the characters did indeed exist, but I wonder if they really performed many of their actions in this film. The events concern not only the Spanish artist (Stellan Skarsgard) but Brother Lorenzo (Javier Bardem), one of the Inquisition’s priests, and Ines Bilbatua (Natalie Portman), the beautiful young daughter of a local merchant.

Goya uses Ines as a model for the angels he paints for churches. He is also a court painter, engaged in a portrait of Queen Maria Luisa (Blanca Portillo), and also a portrait commission by Lorenzo, who recognizes his genius. When Ines is spotted by Inquisition spies declining a dish of pork in a tavern, she is hauled in, accused of Judaism and tortured until she confesses her “sin.” Her father (Jose Luis Gomez) goes to Goya to ask him to intervene with Lorenzo, and all their lives are intertwined.

The Holy Office of the Inquisition referred to torture as “being put to the question.” The theory was God would give you strength to tell only the truth. Ines’ father’s theory is that people will confess to anything if they are tortured, an insight that has never gone out of style. The father persuasively argues this point with Lorenzo, in a scene that Variety unkindly compares to Monty Python. Fifteen years pass; Napoleon conquers Spain and abolishes the Inquisition; Lorenzo, having fled, signs on to the principles of the French Revolution and surfaces as a prosecutor for Napoleon. His job includes jailing the former Inquisitor General (Michael Lonsdale). Meanwhile, Ines is released from the dungeons, where she had a daughter, who …

Enough of the plot. It’s filled with so much melodrama, coincidence and people living their lives against the backdrop of history that Victor Hugo would feel overserved. There are so many dramatic incidents, indeed, that it’s hard to figure out who the central figure is supposed to be. Lorenzo gets top billing, but they’re all buffeted by the winds of fate. I didn’t feel the strong identification with anyone that I had in Forman’s “Amadeus,” but as consolation, I was able to watch enraptured with a visual portrait of a time and place.

Consider an early scene. Footmen for King Carlos IV (Randy Quaid, and very good, too) throw an animal corpse in a field to attract vultures. Then the king shoots them, like pigeons. He also bags some rabbits, but Maria Luisa thinks she’d prefer the vultures for dinner. Other set pieces show the extraordinary cruelty of the dungeons, the obscene magnificence of the royal residences, the bawdy of the taverns, the boldness of the bordellos and streets teeming with life in the midst of death.

The actors invest their characters with surprising depth, considering how the plot has to keep so many story lines afloat. Skarsgard makes Goya into a man with a wonderful smile, an affable manner, and the confidence of an artist who stands outside the rules. Bardem, without making too much a point of it, shows an ambitious man, not enthusiastically evil but capable of the occasional vileness, who can convince himself he is both an inquisitor for the church and a prosecutor for the emperor (the same job, really). Portman plays Ines as a beautiful young girl and as a haggard torture victim, and Alicia as a vulnerable prostitute, all with fearless conviction. And Quaid, in a smaller role as the king, is an inspired if unexpected casting choice, as in a scene where he performs on a violin and almost bashfully confesses he composed the piece himself.

Much of the depth of the film comes from the sound design of Leslie Shatz; we hear precision in the ways vast church doors open and close, we hear far-off bells and echoing interiors, and the sound of shoulders being dislocated is understated but persuasive. And the cinematography of Javier Aguirresarobe is, well, painterly; look at the compositions, the colors, and especially the shading.

Now I must tell you that “Goya’s Ghosts” got cruel reviews when it opened late last fall in Europe. I don’t make a habit of reviewing reviews, but the advance word on this picture was impossible to avoid (“Creaks along like an anemic snail” — Derek Malcolm; “Close to a disaster” — the Telegraph; “Dull as dishwater” — Neil Smith). Sometimes I wonder if critics aren’t reviewing the film they would have preferred rather than the one the director made.

I doubt that Forman and the legendary screenwriter Jean-Claude Carriere lacked the ability to tell a conventional story. I think the clue to their purpose is right there in the opening scene of the Goya drawings. Look carefully, and you may find something in the film to remind you of most of them. “Goya’s Ghosts” is like the sketchbook Goya might have made with a camera.