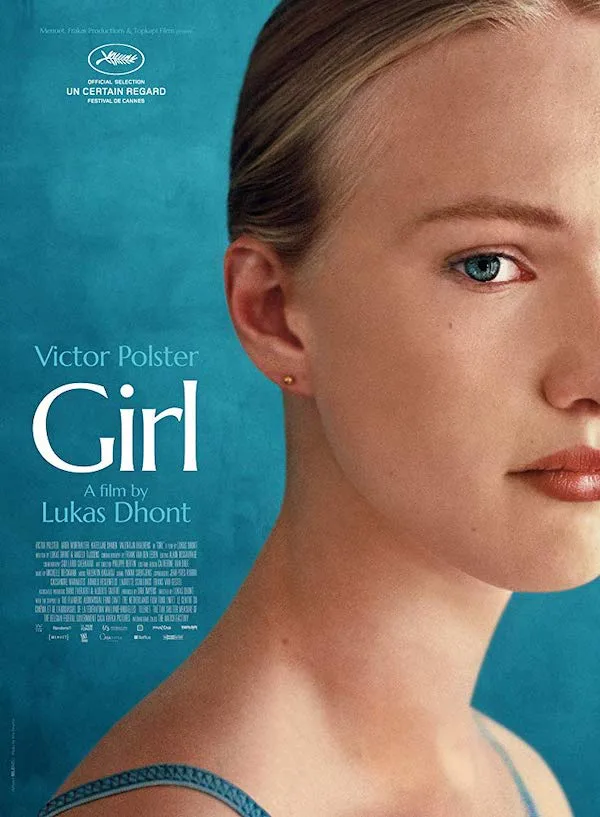

With its release date pushed back a couple of times (never a good sign), the Belgian film “Girl,” a first feature from director Lukas Dhont, limps onto Netflix this week, covered in a cloud of controversy. It began with the news of Dhont’s decision to hold a gender-blind casting call for the lead role of Lara, a trans female ballet dancer, inspired by the journey of Belgian dancer Nora Monsecour. Gender-blind casting may have been well-intentioned but it was a powder keg in this case. Then came news of the casting of Victor Polster, a cis male, in the lead role, which inspired another round of criticism. Although I do my best to avoid buzz (negative or positive), especially if I’m assigned to review, it was impossible with “Girl” (and, in the case of “Girl,” the controversy is a necessary part of the context, as is understanding why people are upset about it). “Girl” debuted at Cannes, winning a couple of plum awards (including the Camera d’Or for Best First Feature), and was nominated for a Golden Globe as well. All along, Monsecour, who collaborated with Dhont through the filming process, has weighed in with support of the film and its intentions, including its graphic depiction of self-harm. All of that being said, does “Girl” work as a film? No. It does not.

The setup, briefly: Lara (Polster) lives with her father and little brother. The family has moved to the city so Lara can attend an elite ballet school. Simultaneously, she is in the beginning stages of gender transition, with hormone therapy, doctor consultations, etc. Her father is supportive of her, but is worried about her moodiness and her fraught relationship with her changing body. Lara has a lot of responsibility in the household, is more like a wife than a daughter, cooking, taking care of her dad and younger brother (who slips up occasionally, referring to Lara as “Victor,” her old name).

The ballet classes are the best parts of “Girl,” with Frank van den Eeden’s cinematography tossing us into the midst of the classes, giving a visceral sense of the experience—the sounds of feet landing on wooden floors, the looks of concentration, the emotional pressure and competition, everyone keeping an eye on everyone else, as well as an overall sense of the overwhelming difficulty of ballet. To be even moderately “good” requires single-minded focus from the earliest age. Lara’s challenges are different from her classmates. She is enrolled in this new school as a female, a controversial decision for her fellow classmates. Lara must devote herself to “catching up” with the other girls, all of whom have been training their feet for dancing en pointe since they were children. Lara has not trained that way, and she works hard with a private teacher, bending and warping her bloody feet into shape. All of this is really interesting!

Unfortunately, “Girl”‘s fascination with Lara’s gender transition translates into a leering focus on her genitals, shoulders and chest. Even disregarding the controversy, “Girl” does not work, mainly because Dhont’s focus is all wrong. What’s interesting in the story—Lara’s experiences as a trans ballerina—is treated as background noise, or at least secondary to the obsession with what her body looks like. There’s something voyeuristic about a camera zooming in repeatedly on a teenager’s groin. Looping Lara’s body hatred (there’s no other word for how it’s portrayed) in with being a ballet dancer seems like it would make sense—there’s a lot of overlap—but that’s not really explored. Instead, the camera seems to ask, repeatedly, “What’s going on in her crotch?” Against advice, Lara tapes down her genitals, and there are numerous scenes of her rashes, her taping process, the pain it causes her. There’s a very graphic scene of self-harm late in the film. The result of all of this is, I believe, unintended on the part of the director.

“Girl” is meant to be an inspiring story of a person becoming who she wants to be. The seeds of that story are there in her private sessions with a ballet tutor, and in how hard she works at whipping her feet into pointe shape. It’s inspiring! But the film’s focus on her body and her increasing impatience to transition—her hatred of her body leading her to that act of self-harm—makes “Girl” a film about a child having a nervous breakdown. Drawing a link between being trans and having a nervous breakdown—and, worse, positioning her self-harm as the ultimate act of liberation—is extremely irresponsible.

Polster has received praise for his performance, but I found him a lackluster onscreen presence, capable of playing only one note, and a boring note at that: the eye-rolling uncommunicative teenager. The challenge of casting Lara is obvious: whoever got the job had to be able to do the dancing. But Lara, as played by Polster, is non-revealing, quiet, and sullen. Her father keeps asking her what’s wrong, and she says “Nothing” or “I don’t know” over and over again. Teenagers can be like this, it’s true, but a whole film of it is tiresome. There’s no way in, especially when the camera keeps moving away from Polster’s face, away from his bloodied hard-working feet, to his groin, again and again. Enough already.