At one point (ok, several points), I wanted to write off “Genesis 2.0”—a speculative documentary about the present and potential hazards of excavating mammoth tusks for genomic research and animal cloning—as irresponsible, superstitious, anti-science garbage. But I sat with the film for a few days, and now I think this film’s biggest problem is its emphasis on media-friendly personalities instead of useful information. That’s not unusual given that many contemporary documentaries are seemingly made by filmmakers who idolize and/or imitate Michael Moore and Werner Herzog. Still, Moore and Herzog’s respective approaches are very difficult to pull off (for proof, see: their more recent films), especially when your subject is as dry as scientific research and the many factors that contribute to its study and application. “Genesis 2.0” passively asks viewers to make assumptions about the character of several of its subjects—mostly white-collar scientists, but some blue-collar “mammoth tusk hunters,” too—based on incomplete or vague insinuations. This movie doesn’t work well as an edifying documentary, but it might go over well with anyone who wants to follow its unconvincing conspiracy-theory-like logic (apparently, genetic research is bad because it’s “playing God” and is partly underfunded and overseen by the Chinese government and cocky American scientists!).

“Genesis 2.0” begins with an ominous scene: a pair of adult Siberian men guide a small motor-boat through unidentified icy waters (later revealed to be the Arctic Ocean, surrounding the “New Siberian Islands”). An equally unidentified woman provides some commentary (through voiceover narration), but not enough to make this preface seem that much more sensible. Mostly because the commentary that the narrator provides is cryptic and upsetting: “Fatuous and boasting you are[…]You, a credulous fool!” It doesn’t help that this ominous commentary—”How did you manage to set free that terrible Devil”—is goosed by a quietly unnerving strings-heavy piece, composed by Max Richter and Edward Artemyev.

But soon, the filmmakers contrast their film’s opening scene with another sequence: an unnamed speaker at an American press conference called “iGem” (International Genetically Engineered Machine Foundation) delivers a plain-sounding speech about a “revolution” in a field of study called synthetic biology. This revolution will, in time, only continue to grow. Then, some spare inter-titles tell us: “Every summer, students from all over the world gather in Boston USA” [sic] “They set off on a journey to a tempting future.” Yeah, but, like, why?

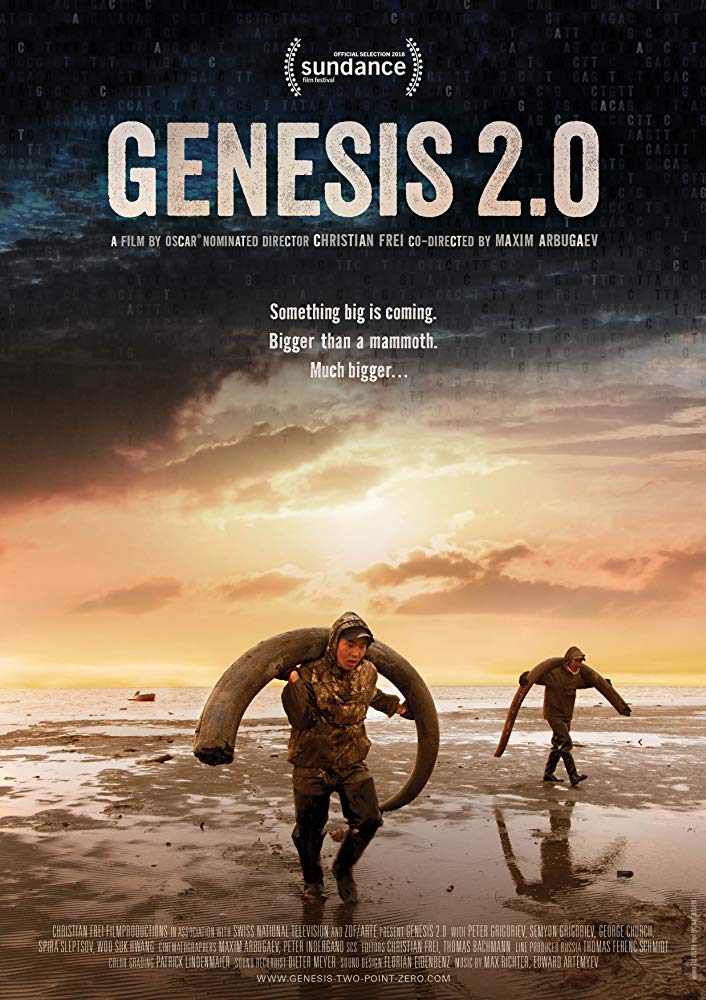

Some of my burning queries were, in fact, answered as I watched “Genesis 2.0.” But the answers I got were somehow even more dissatisfying than my questions (if you can imagine that). We’re shown Siberian working-class mammoth hunters as they struggle to find valuable mammoth tusks that are buried in the New Siberian Islands (surrounded by the Arctic Ocean). The mammoth hunters’ relatable struggles and taciturn nature makes them great camera subjects. They are noble and stoic. They look like action heroes, and they behave just like you or I: they try to call home, try to find food, try to make a buck, try not to die.

Compare that with the way that co-directors Christian Frei and Maxim Arbugaev—the latter of whom also served as the film’s cinematographer during the New Siberian Islands’ scenes—film George Church, a famous American geneticist who sometimes stops to sign autographs for excited high school students who appear to recognize him. Church smiles a lot for various cameras. He also speaks eloquently, though he also never seems to say anything about his studies’ moral implications. That—all of that—is a big no-no in the eyes of this film’s co-creators, who may or may not have asked Church, “Hey, what are the moral implications of your studies, and why don’t you seem to be as worried as we are?”

At least Church’s apparently un-introspective behavior paves the way for the valorization of Siberian mammoth expert Semyon Grigoriev, who we always see thinking, consulting, negotiating, doing. Semyon—whose brother Peter is the most well-developed of the film’s mammoth hunter characters—always seems to be thinking about where his research is coming from and what it will be used for. We’re supposed to like Semyon and are therefore only shown one side of his personality: the attractively thoughtful side. Everyone else in “Genesis 2.0″—including Peter and George—is eventually revealed to be either a likely dupe or a potential fraud. What a world, what a story.