What has hardly been known is how the Nazis were deluded. It was largely the work of a single man, Juan Pujol Garcia, a Spaniard who fed the Nazis a stream of misleading information from a spy network that existed entirely in his imagination.

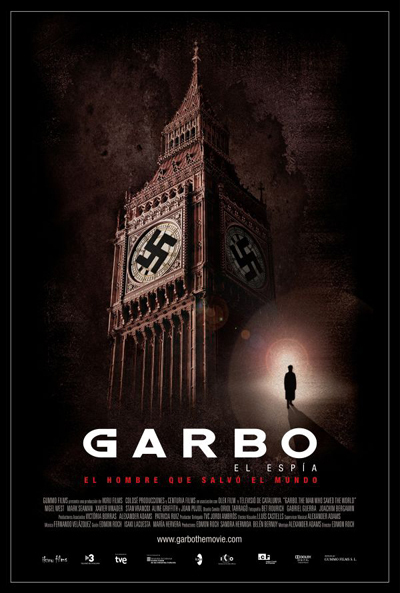

Edmon Roch‘s “Garbo the Spy” is an engrossing documentary that is itself largely a work of the director’s imagination. Garcia was code-named “Garbo” because one of his handlers considered him “the greatest actor in the world.” Impersonating a man who controlled sources that never existed, he sold the Nazis so convincingly that when he decided one of his spies had to die, the Nazis paid his “widow” a pension.

Based partly on Nigel West’s book Operation Garbo: The Personal Story of the Most Successful Spy of World War II, the doc tells the story of an elusive young man from Barcelona who wanted an effect on the war and volunteered his services not once but four times to the British. They eventually accepted him after he had already set up as a free-lancer, feeding his own Nazis contacts information from his fictional network.

Moving to Lisbon, a hotbed of intrigue in Nazi-occupied Europe, he made up most of the information passed on by his “network,” and enough of it was true that the Nazis believed him. Over one period of nine months, he even convinced them he was in London. His masterwork was to inform them that the Allies would fake a landing at Normandy to lure the German army there, and then unleash Patton’s surprise attack at Calais. They believed him. The fiction worked so well that the Nazis never were up to strength at Normandy, and the fabled Panzer division, while en route there, was diverted to Calais instead.

By this point, the Allies were working closely with Garcia. Three hours before the D-Day attack was timed to begin, Eisenhower personally authorized Garcia to tip off the Nazis, reckoning they wouldn’t have time for troop movements. In a stroke of luck, when Garcia’s message arrived, the Nazi communications center was unstaffed, and so when they discovered his timely warning hours later, he looked even more reliable.

Incredibly, weeks after the invasion, he continued to convince them the real target was elsewhere. When they asked why the attack at Calais never came, he explained: “They had such unexpected success at Normandy, they decided to cancel it.” The Nazis continued to believe Garcia to the end, and he became the only man decorated by both sides in World War II.

Only two early photographs of Garcia exist. “Garbo the Spy,” perhaps inspired by its subject, is made up partly of smoke and mirrors. Director Edmon Roch uses vintage newsreel footage and scenes from old spy movies to illustrate his story, narrated by a series of talking heads, including Nigel West himself. Some of the footage shows Alec Guinness in “Our Man in Havana” (1959), a movie based on a Graham Greene novel inspired by Garcia.

West was able to trace Garcia’s postwar movements to the Portuguese colony of Angola, where he reportedly died in 1949. Not so. He slipped away to Venezuela, operated a movie theater, married and had children. The film concludes with an enormously affecting series of scenes in which the elderly Garcia revisits the beaches of Normandy and an Allied cemetery. Perhaps fittingly, he never speaks.