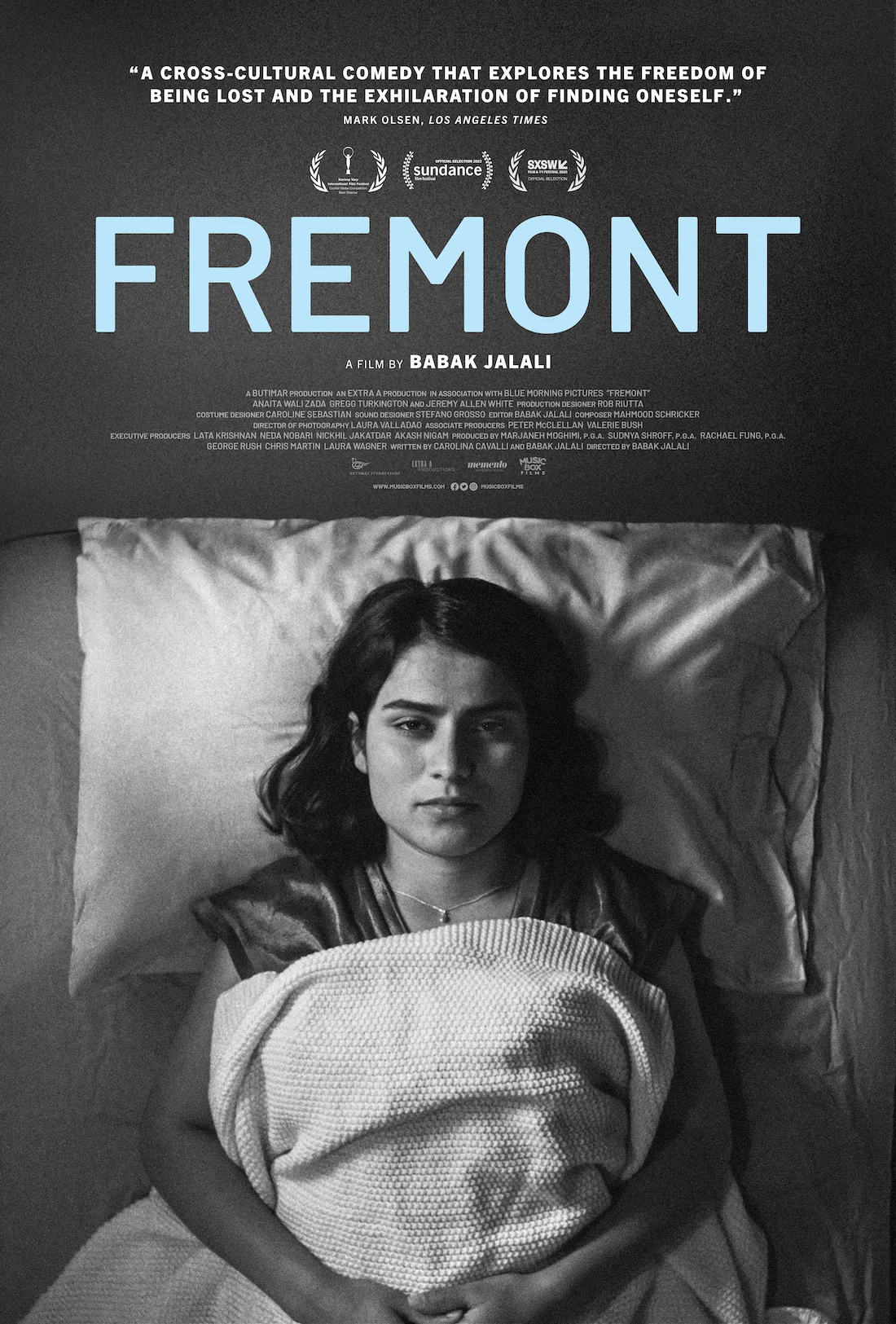

Filmed in stunning black and white, Babak Jalali’s “Fremont” is visually captivating as it renders California’s East Bay as a character of its own. However, it never outshines the film’s focus: Donya (Anaita Wali Zada). Donya works at a fortune cookie factory, writing the sentiments inside. But as she doles out fortunes for those around her, she struggles to clinch her own.

Donya can’t sleep. She spends her nights in a twin bed staring at the ceiling and her days going from the cookie factory to her awkward but thoughtful therapist. Donya is an Afghan refugee (as is Zada) who served as a translator for the United States Army during the war. For this, she carries survivor’s guilt that sours the idea of “moving on.” Donya feels that a life of love and enjoyment is unfair when so many Afghans live in a country plagued by war. As she vies for an existence of connection and contentment, “Fremont,” and intrinsically, its heroine, are marked by a feeling of displacement.

Donya floats through her days with little stimulation or decision, a stringent routine followed by a lackluster evening of wakefulness. The film’s sound design holds a sharp presence that absorbs us within her world. “Fremont” is quiet, and its silence has a reason, holding the weight and impact of conversations in the film’s dialogue-heavy format. From deep breaths to fingers tapping on desks, the occupancy of a character in a scene is often the only sound we’re afforded. When the score is present, its inclusion is resonant, marking a moment of uncertainty or transition.

Conversation is the backbone of “Fremont,” which is written by Jalali and Carolina Cavalli. Donya is the film’s first and foremost priority, and it’s not just her moments in solitude but her limited conversations with those around her that color her perspective. From a somewhat nosy but amiable work friend to an elderly restaurant worker she spends evenings watching soap operas with, Donya is always at arm’s length from true connection. An Afghan woman in her apartment complex is the closest thing she has to a friendship of mutual understanding, but her husband despises Donya, seeing her as a traitor for having worked with the United States Army.

Zada is excellent as Donya, undoubtedly reaching from a sincere source as a refugee herself. Donya’s exhausted stoicism and touches of sarcasm excellently paint a woman who is tired but trying. As low lids, slow blinks, and a still body express her spiritual depletion, when Zada triggers a subtle smirk or a witty response, we see a shadow of the woman Donya is beneath the shame. Laura Valladao’s black and white images are incredibly intimate, filled with various stunning close-ups, where expression and texture fill the screen with feeling.

As we spend the film’s 86-minute run time getting to know Donya, we witness the little bumps of intonation in her monotone speech. We can discern minute changes in her disposition that point to nervousness, hope, annoyance, and dejection. This is a testament to the tight grip that Zada has on Donya’s truth and authenticity. The terrific nuance of her portrayal is utterly real. It makes us feel like we truly know her. Her performance doesn’t lay it out flat; it gives us empathetic credit.

Donya yearns for sleep, stable ground, love, and fulfillment. A beacon finally comes in the film’s final act via an innocuous but impactful run-in with a timid, though very charming mechanic played by Jeremy Allen White. This meet cute is endearing enough, and Zada and White’s chemistry translates through the screen, but it’s a notable divergence from the value the film had built thus far. Such a tacked-on romantic subplot feels overly convenient and simplified, undercutting her agency and self-efficacy with a white knight in a dirty jumpsuit. White’s inclusion is well executed, and yet the absolution it is treated with is unneeded. Love is only a modicum of Donya’s story. The perspective of immigrant guilt and her desire to overcome herself is markedly treated with more interest and heft elsewhere in “Fremont.” But the film treats the potential of a romance with a resolve that feels like a familiar, vacant bullet point from many female-forward narratives previously written by men.

“Fremont” contains a notable calmness in its filmmaking, and its gorgeous lead performance quietly reaches poignance without flamboyance. It is a stunning mood piece that takes pride in its stillness and slow pace, ultimately delivering a tale of intimacy, searching, and quiet strength.

Now playing in theaters.