This review was originally published on December 8, 2017 and is being republished for the NY/LA release.

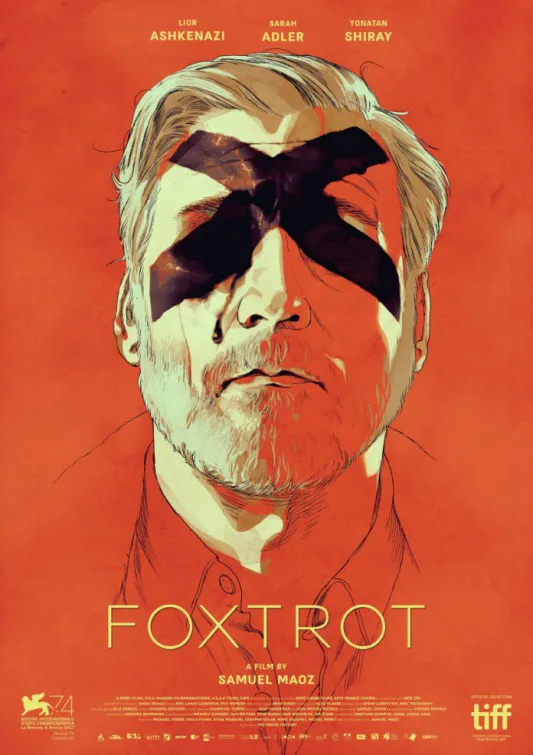

Twenty years ago, Israeli writer/director Samuel Maoz refused to give his daughter the money to take a cab when she was running late for school. He sent her to a bus stop, hearing 20 minutes later that the bus line she was taking was hit by a terrorist attack. He would learn that she missed the bus, but for a terrifying window of time, his daughter was dead, and he felt some responsibility in sending her to that death. This unforgettable day became the inspiration for Maoz’s second film, the award-wining “Foxtrot,” a searing and phenomenal examination of what writer Paul Auster called “The Music of Chance.” It is a formally gorgeous piece of work, the kind of film that exudes confidence in structure and tone, and it contains some of the most striking, memorable imagery of the year. Don’t miss this one, either in its Oscar-qualifying run this week or when it’s released wider next year.

“Foxtrot” opens with a knock on a door. A woman, Daphna Feldmann (Sarah Adler), answers and immediately falls to the ground. She knows what the arrival of Israeli soldiers at her door means—her son Jonathan has died in the line of duty. The arriving soldiers confirm this news to Dafna’s husband Michael (the excellent Lior Ashkenazi), and Maoz’s formalism is instantly clear and striking. He opens his film with procedure. It’s not just the information of the death of a child but the procedure that entails. The soldiers tell Michael to make sure he drinks water, asks if they should call someone—and we stay on Michael’s face. This is procedure for the men telling but not the man being told. When they leave, Maoz cuts to a dizzying overhead shot, spinning his typically-static camera in a way that reflects the unstable world of our protagonist. This is the kind of filmmaking—in which formal choices are clear and striking—that one immediately recognizes as accomplished, intertwining visual art with deep wells of emotional impact like grief and anger. Maoz uses his skill as a visual artist to enhance the human urgency of his story.

And what a story it is, although I wouldn’t spoil much of where it goes after that opening scene. Let’s just say that the second act of the film jumps to a remote Israeli checkpoint where four young men fight the monotony of a gate that’s raised more often for wandering camels than anything else. In long, often silent sequences, we watch these still-boys stuck in the middle of nowhere with almost nothing to do but count the days until they leave. They tell stories and play games—and a scene of one of them playing a shooter like “Call of Duty” and asking “what are we fighting for here” feels a bit too on the nose to me—and try to do anything to alleviate the boredom, until tragedy strikes completely out of nowhere. The final act takes us back to Tel Aviv as Maoz digs deeper into the themes of loss and fate inspired by the story of his daughter and the bus.

“Foxtrot” blends stark, drab realism with the kind of images only film can provide. A soldier dances with his gun at a checkpoint, a bulldozer lifts a car, a camel walks through a checkpoint like it’s part of his routine, a grieving father watches a dance class, the world going on even though his has changed—Maoz’s film is one in which it feels like every decision has been carefully considered like a note in a symphony. “Foxtrot” is at its best when it feels the most open to interpretation—even the title, a dance in which the dancer returns to the same place he started, has meaning, of course. It’s a film designed to move you with its depiction of senseless tragedy but also to spark that part of your thinking process that only moviemaking can tap. It has been a controversial film in Israel for one of its plot points, but it feels to me like a movie that speaks to cultures and people around the world. It is both specific and universal at the same time. It may have been inspired by a very personal day of near-tragedy that Maoz will never forget, but this multi-talented filmmaker has taken that darkness and turned it into something unforgettable for everyone who sees it.