After watching the first 20 minutes or so of the new romantic drama “Felix and Meira” without being especially impressed with anything that I had seen up to that point, I began to fear that there might be a certain cultural divide that was keeping me at arm’s length from a dramatic standpoint. After all, it tells a story that deals in part with the customs of the Hasidic Jewish community and as someone who could politely be described from a theological perspective as a lapsed Lutheran at best, it could be argued that there was something in the nuances that I just wasn’t getting and which was preventing me from embracing the story either narratively or emotionally. As it went on, however, I was relieved to discover that my problems with the film were not the result of any spiritual shortcomings on my part but from the inescapable fact that it tells a not-especially-interesting story about a not-especially-interesting couple from two different worlds that goes on and on before reaching its not-especially-interesting conclusion.

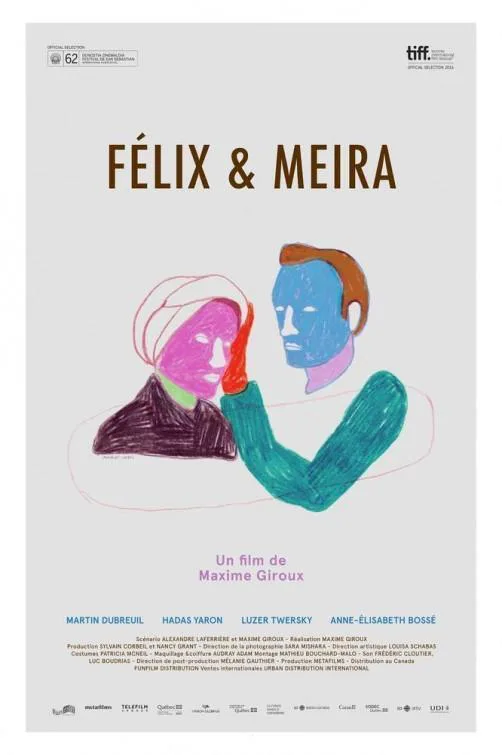

Meira (Hadas Yaron) is a miserably unhappy young woman who is feeling increasingly smothered by her uber-orthodox husband Shulem (Luzer Twersky) and the closed-off Hasidic community where they reside in Montreal—other than her young daughter and the pop music that she secretly listens to as a release after Shulem leaves the house to attend morning prayers, her life is as grey and lifeless as the slushy city streets. Felix (Martin Dubreuil) is an aging hipster with no apparent attachments—emotional, spiritual or professional—to speak of who has returned to visit his estranged father on his deathbed. Although devoid of any of the encumbrances that are tying Meira down, he also finds himself similarly trapped in a spiritual prison from which escape seems impossible.

After an initial meeting in a local pizza shop, Felix encounters Meira on the street one day following his father’s death and chats her up with the deathless pickup line “Can you give me advice? You are religious and I don’t know what I am.” Okay, it doesn’t sound like much and even Meira rejects his company at first but before long, she turns up on his doorstep and a friendship begins to develop between these two people from different worlds. For her, these encounters allow her to indulge in small rebellions, ranging from trying on a pair of blue jeans to looking a man in the eye while talking to him, that do not go unnoticed by Shulem. For Felix, he also begins to come out of his shell and when it seems as though he will no longer be able to see Meira again, he goes so far as to dress up in Hasidic garb in order to infiltrate her community and get close to her.

In theory, this all sounds nice enough and I suppose I can see how it might have been spun out into a compelling film, provided that an interesting narrative and characters were part of the package. That, alas, is where director/co-writer Maxime Giroux comes up short. The lives of these two characters may be airless and stultifying but unfortunately, so are their stories. We barely get to know anything about who Felix and Meira are, how they found themselves in their current circumstances or what it is that they see in each other that serves as a counterpoint to their current existences—frankly, they often seem just as glum when they are together as apart. Giroux doesn’t seem particularly interested in fleshing them out for the most part, instead preferring to spend his time on such unlikely twists as Felix disguising himself (which may have been conceived as a comedic touch but which is played so heavily that whatever laughs might have been there never come) or an inexplicable later meeting between Felix and Shulem. The only moments of real emotional release come with a couple of deft soundtrack choices—Wendy Rene’s “After Laughter Comes Tears” as Meira’s illicit musical selection, an old video of Sister Louise Tharpe rocking out on a train platform and Leonard Cohen’s “Famous Blue Raincoat” swelling up as Meira watches a couple making love through a window while standing on a dark street—but in those cases, the achievement belongs to the film’s soundtrack supervisor and not to Giroux.

Back to my initial statement about how I thought at first that my problem with “Felix and Meira” was a cultural one. One of the reasons I was able to dismiss that notion was because I remembered a movie that dealt with the Hasidic community that I really did like from a couple of years ago entitled “Fill the Void.” Coincidentally, that film also starred Hadas Yaron—whose performance is the best thing here, it should be noted—and told the story of a young woman being pressured to marry the much older husband of her recently deceased sister, a move that will satisfy the needs of the community but which holds little appeal to her personally. By telling the tale of a woman yearning to escape such a situation despite the overwhelming odds, “Felix and Meira” is essentially the inverse of “Fill the Void” from a dramatic standpoint. Sadly, it turns out to be the inverse of that film from a qualitative standpoint as well.