Alain Gomis’ “Félicité” opens on the hustle and bustle of a small Congolese bar as the talkative, inebriated patrons wait for the evening’s performance. Gomis and his DP Céline Bozon capture the dark, freewheeling atmosphere with intimacy and tact. Bits of conversation trickle in and out of the soundtrack. Tender close-ups of patrons briefly dominate the frame. A loud drunk makes his presence known. Meanwhile, the Kasai Allstars perform a lively song that scores the evening’s events. In this scene, Gomis never overtly highlights a central figure or even indicates a particular narrative. He simply marinates in the mood, trusting his audience to follow the tenor of the environment.

In “Félicité,” Gomis never settles into one particular rhythm, preferring to flex his range with different styles, each with their own specific tones. Though technically anchored by a narrative, “Félicité” never feels particularly beholden to it. Gomis merely uses it as a springboard to explore multiple different aesthetic avenues. The film routinely takes the form of a street level documentary, a concert film, and a near-silent character study. Gomis packs his movie with multiple interludes that are digressive but feel integral to his vision. Pardon the obvious description, but the sheer musicality of “Félicité” signals Gomis’ refusal to be pigeonholed into any category of filmmaker.

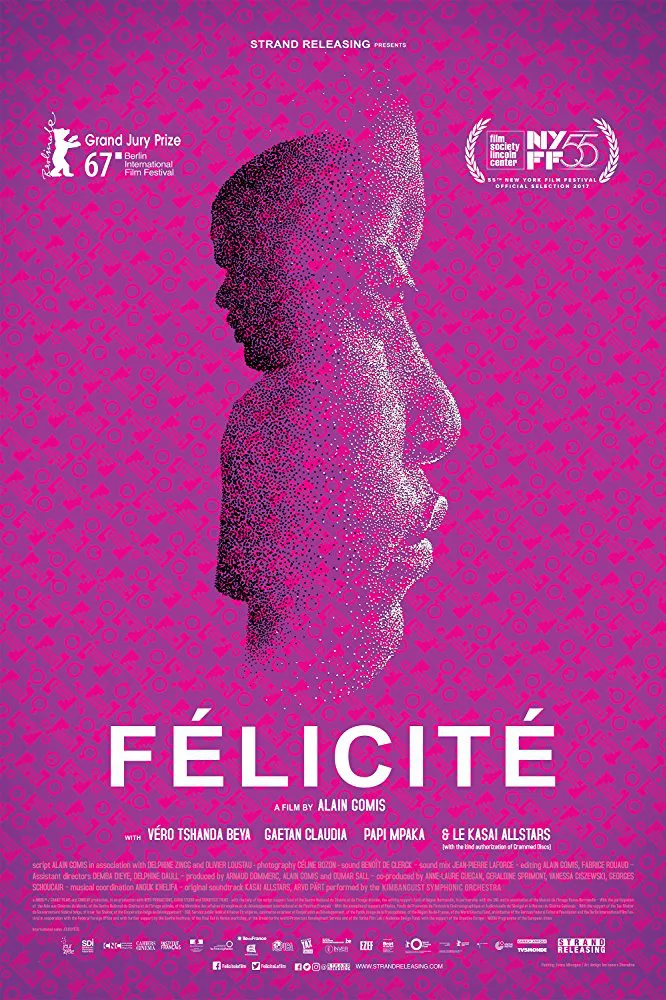

Paradoxically, the initial narrative so strongly compels that it’s difficult for “Félicité” to recover after it runs its course. The film’s title character (Vero Tshanda Beya, in an astonishing debut performance), a single mother and a club singer living in Kinshasa, lives her life independently. But when her 14-year-old son lands in the hospital after a nasty motorcycle accident, she embarks on a quest to gather the money necessary for an operation to save his leg. Gomis follows this proud woman as she rushes around the entire city collecting old debts and begging for money to help her son.

Félicité’s strength derives from her staunch refusal to collapse under the weight of her circumstance. Bozon frequently captures Beya’s face in tight close-up as she silently maneuvers through the chaos of the city, struggling to gather the necessary funds before it’s too late. It’s clear that Félicité isn’t one to ask or even beg for anything, let alone money from her cash-strapped peers and family members, but the position has rendered pride a luxury. The character and Beya’s performance recalls Marion Cotillard’s character in the Dardenne brothers’ recent feature “Two Days, One Night”; Cotillard plays a desperate woman who must beg her colleagues to vote to keep her job, all while she combats her own mental illness. Watch Beya as she refuses to turn away from insults hurled at her face, or when she stands up to a local mob boss who refuses her request for a handout. Beya channels the unique power in simply refusing to yield to the world’s harsh burdens.

Gomis majorly shifts gears in the film’s second hour, moving away from the established narrative into broader territory. He focuses on Félicité’s personal journey, primarily her new relationship with a sweet local mechanic and frequent drunk Tabu (Papi Mpaka), as well as capturing Kinshasa street life. Though this has frequent pleasures, like a showcase for Mpaka’s tender yet boisterous performance, it doesn’t retain the urgency of the film’s first hour. While the meandering interludes initially felt attached to Félicité and her plight, they eventually become too tenuous for them to have much impact. Worst of all, Gomis struggles to arrive at an appropriate conclusion; he chooses to end “Félicité” a few different ways, all of which have weight on their own, but less so when juxtaposed.

Still, “Félicité” has a lyrical spirit that worms its way to the surface even at its most directionless, especially when Gomis squarely focuses on musical performances from the Kasai Allstars and the Symphonic Orchestra of Kinshasa. The former brings an exuberant energy, deriving from their mixture of multiple ethnic traditions, while the latter provides an ethereal quality that suggests an otherworldly presence within the frame. Gomis weaves the music through Félicité’s personal exploration, providing extra potency to her soul search. “Félicité” argues that the world keeps spinning when any given crisis finishes. The key is to keep up with it on your own terms.