“Farewell, My Queen” begins early in the day of July 14, 1789, at the royal palace of Versailles. It was not yet a date fraught with destiny. In the rat-swarming servants’ quarters, a young woman named Sidonie Laborde slaps at mosquito bites, hurries through her toilet, and runs toward her appointment with Marie Antoinette. She is the official reader to the queen, and this position gives her a limited stature and some access to the royal life of luxurious decadence.

Over the next three days, we will witness life at Versailles exclusively through the eyes of Sidonie (Lea Seydoux). Reports arrive at Versailles that the Bastille has been stormed, and although this is never publicly acknowledged, it spreads as circles of rumor through the ranks of the servants, some of whom perhaps only vaguely understand what it means — and what it will mean for them personally. The vast, all-powerful edifice of the French monarchy will be swept away in a matter of days, and Marie Antoinette and her husband Louis XVI will inevitably be beheaded.

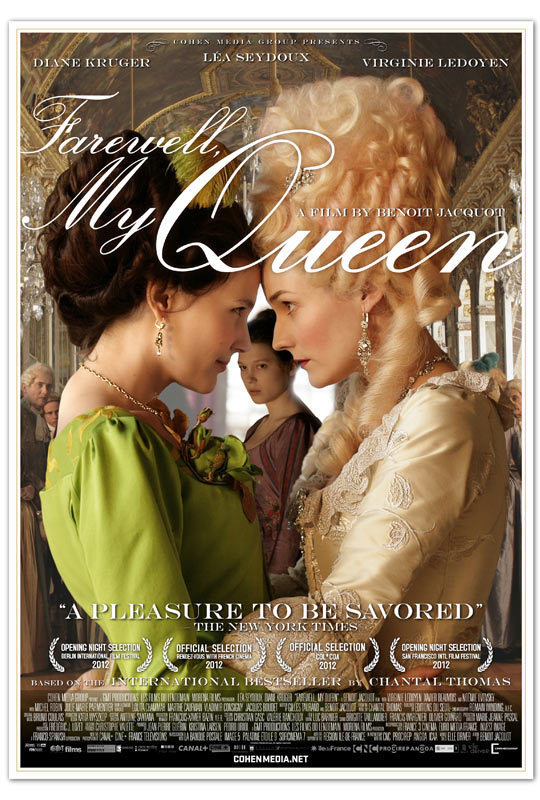

On this morning, that seems inconceivable. The queen (Diane Kruger) reclines in her private chamber, closely guarded over by her lady-in-waiting, Madame Campan (Noemie Lvovsky). She has apparently spent the night with Gabrielle de Polignac (Virginie Ledoyen), said to be her lover. Now the young Sidonie enters and begins to read to her mistress. Their relationship seems relaxed but not privileged; Sidonie is a utility, like a radio in later days, who can be turned on and off at the queen’s whim. The palace room, rich in tapestries and art, is a stark contrast to the rude stone walls of Sidonie’s own room, but so embedded is the Queen’s Reader with the majesty of privilege that she accepts this without question. Kings and queens rule by divine right. This calm and stability will disintegrate with shocking speed over the next few days, and it will dawn upon Sidonie that the earth is shifting beneath her feet.

Benoit Jacquot’s engrossing film tells a story we know well, seen from a point of view we may not have considered. Based on a novel with the same title by Chantal Thomas, it is limited to what Sidonie can know and understand. Since all of the mounting horror takes place at a distance, in whispers, in a way it’s more dreadful than if she were learning things firsthand. The servants in a place like Versailles subscribe completely to the majesty of their employers, and although they may have no access to outside news, they are sensitive to the slightest shifts in mood from their masters. Gossip races through the palace in back corridors and down hidden staircases, and it is worst at night — when a few candles make the shadows seem more limitless.

Jacquot actually filmed many of his scenes at Versailles, but takes care to display it warts and all. One imagines the body odors, the stink of dead rats, the miasma rising from the slops, the perfumes splashed on for concealment. As the iron discipline of the palace management begins to fall apart, servants focus on their own fates. There is a fascination to be found in those who discover their sense of security has no foundation. I was reminded of “Downfall,” the film about the final days in Hitler’s bunker beneath Berlin. Its walls contained the last space ruled by Hitler’s once-mighty will, and those within knew they were doomed.

“Farewell, My Queen” places Sidonie in such a position. As a woman who can read and write in 1789, she must be intelligent and ambitious. She must also have learned much from the books and journals she read for the queen. This does much to account for her fate in this film. I wouldn’t say “Farewell, My Queen” has a surprise ending, but it is certainly surprising and has the kind of neatness that comes through poetic justice.