What does Sidney Lumet’s “Family Business” want to be? A caper movie, or a family drama? I ask because the movie seems to pursue both goals with equal success until about the three-quarter mark and then leaves leftover details of the caper hanging disconcertingly in midair.

I was distracted during the movie’s important final scenes by a large unanswered question, which I’ll get to later.

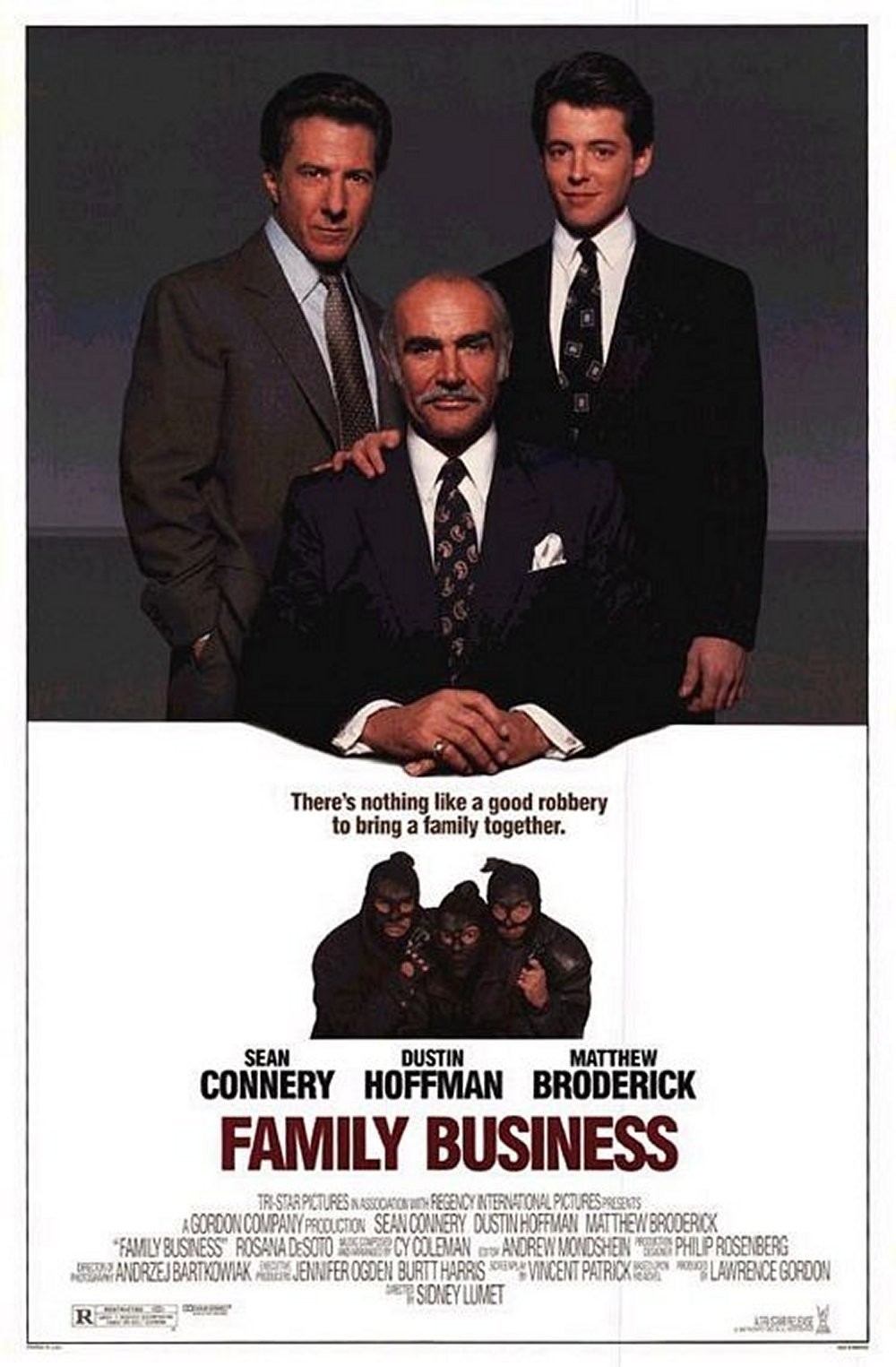

Good news first. The movie stars Sean Connery, Dustin Hoffman and Matthew Broderick as three generations of the same family, all touched one way or another by crime. Connery, the grandfather, is a Scotsman whose arrest record is as long as his arm. He lives by one of those macho criminal codes in which you haven’t proven anything unless you’ve proven it with your fists, and as the movie opens he’s in jail after getting in a bar brawl with an off-duty policeman.

Hoffman is Connery’s son, half Scots and half Sicilian (“He’d be 5 inches taller with a Scots mother,” Connery observes), and Broderick is Hoffman’s son, half Jewish. The movie makes such a point of the hereditary makeup of the three men, I guess, because the caper involves breaking into a genetic engineering laboratory and stealing some DNA research material. The idea for the caper comes from Broderick, a Westinghouse Scholar who has never been involved in crime before. Hoffman is adamantly opposed to it – he still bears the wounds of his childhood with a criminal father – but Connery is enthusiastic, and Hoffman finally decides to come along out of concern for the safety of his son.

All of the scenes establishing the characters and setting up the caper are joyful to watch, mostly because of the rich comic exaggerations of the Connery character, who makes such a contrast to his uptight son and all-American grandson. The caper itself is a disappointment (they have a key card and a security code, after all, so we’re not talking brain surgery). The aftermath gets interesting when Broderick makes a stupid mistake and is collared by the cops, and Connery and Hoffman have to decide whether to turn themselves in to help the kid avoid a prison term.

It’s going to be tricky explaining that big question that I think the movie leaves hanging. Without revealing too much, here goes.

There is a crucial scene in which Connery corners the Chinese-American scientist who had originally hired them to steal the DNA material. The scientist tells him something that, if brought out in open court, would certainly lead to the whole case being seen in a different light. But the movie ignores this new material and goes in another direction, leaving us patiently waiting for a big courtroom scene that never arrives. They should have either left the scientist out or dealt with his information.

The closing scenes of the movie are a disappointment for more reasons than one. What happens to Connery is sudden, unprepared and dramatically unsatisfactory. And then what happens between Hoffman and Broderick seems to belong in a different kind of movie. “Family Business” tries to play it down the middle, when it probably should have jumped in one direction or the other, toward a pure caper or toward a family drama. The problem with capers and courtrooms is, once evidence is on the table, the audience can hardly think of anything else until it’s disposed of.