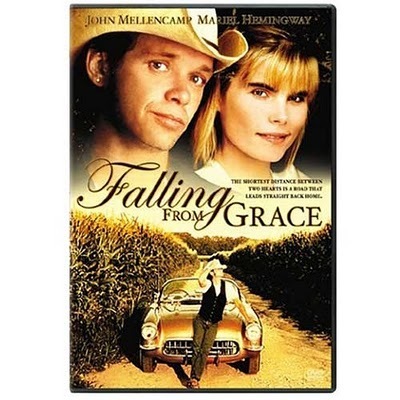

Thomas Wolfe told us “You can’t go home again,” and people who have never read a word of his novels remember that warning, perhaps because it is so obviously true. And still people try to go back home. In “Falling from Grace,” John Mellencamp‘s powerful first film, a country-rock star returns to his small town in Indiana, hoping to throw back a few brews and hang out with his old buddies at the pool hall. It doesn’t work out that way.

The Mellencamp character left more than memories behind in Indiana. He also left an alcoholic father (Claude Akins), whose idea of an ideal male role falls somewhere between patriarch and rapist.

And he left behind an old girlfriend (Kay Lenz), who has now married the hero’s brother but who has spent a lot of years thinking the singer should have taken her along when he left for the big time.

John Mellencamp, of course, is a rock star who comes from Indiana himself, and often goes back there – so often it is unlikely “Falling from Grace” is autobiographical except in its broadest and least personal outlines. What he has done, I imagine, is to combine Larry McMurtry’s uncommonly good original screenplay with his own small-town insights, and the experiences of all sorts of other people he’s met or worked with on the road. They all come together in this story where old wounds never heal.

One of the strangest truths about high school reunions is that all of the old jealousies and resentments of years before are still remembered so clearly; the people who sat together in the school lunchroom now sit together at the reunion banquet, as if the years in between haven’t made a difference. We get that same sense of wounded memory in the opening scenes of “Falling from Grace,” as Mellencamp’s private plane arrives at the local airport, disgorging the singer, his wife (Mariel Hemingway) and his entourage.

Word quickly gets around town that Mellencamp is back, and it is especially quick to reach Kay Lenz, the sister-in-law. The situation resembles, I suppose, a script from “Dallas” or “Dynasty” (returning rock star still feels chemistry with sexy old flame, now married to his brother), but McMurtry doesn’t write it that way. His screenplay is too intelligent, and too observant.

Kay Lenz has many of the best scenes in the movie. She plays a woman who has achieved some degree of material comfort (she lives in one of the best houses in town), but no psychic or emotional satisfaction. She fools around all the time, and everyone in town knows it, and she doesn’t care that they know.

The Mellencamp character comes back to town with the idea that everyone will be more or less happy to see him. He is wrong. His friends and relatives have spent a long time thinking about his life in the fast lane, and there are a lot of jealousies and resentments.

Lenz is particularly angry. She knows she was smart enough and pretty enough for him to take along when he made his break, and if he’s going to come back she isn’t going to simply smile and bite the bullet.

While Hemingway, as the singer’s wife, sits around bored and ignored, and pawed by the singer’s randy father – who treats her like a toy that his son brought home for Dad – Mellencamp and Lenz engage in a hostile and risky flirtation. This could have been soap opera material, but McMurtry’s screenplay is based on a lot of psychological insight, and we see how old issues and old wounds are still able to affect the present and change lives.

A lot of rock stars and other showbiz heroes have the notion that because they’re successful in other areas, they can direct a movie, too. Usually they’re wrong. But Mellencamp turns out to have a real filmmaking gift. His film is perceptive and subtle, and doesn’t make the mistake of thinking that because something is real, it makes good fiction. The characters created here with McMurtry are three-dimensional and fully realized – and the Lenz character is probably even better-seen than Mellencamp’s. At the end of the movie we are left with the possibility that although you may be able to go home again, it might be a good idea not to.