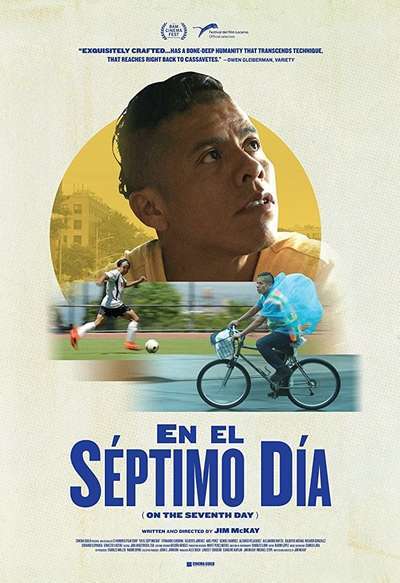

There are three moments in “En el Séptimo Dia (On the Seventh Day)” where director Jim McKay lingers, holding the camera on an object or a person, long enough so it calls attention to itself. One is a low-angle shot of a bike locked to a post outside a Brooklyn office building; one shows hard-working delivery guy José (Fernando Cardona) inhaling a burrito on his lunch break; and one shows a singer performing a song on an empty sidewalk, guitar case open on the pavement. Each shot increases its impact the more you think about it. “En el Séptimo Dia” doesn’t give you much time to breathe or think (the characters don’t have time for it either), so each quiet moment has an important place in the narrative, and each illuminates a different aspect of the lives of the characters, a group of undocumented immigrants from Mexico living in New York City. “En el Séptimo Dia” makes its points powerfully, even more so since the set-up is so simple. Even better, its third act is as thrilling as anything in a traditional sports movie. McKay‘s control of tone and rhythm is in high gear, creating a work both thought-provoking and hugely entertaining.

The group of men in “En el Séptimo Dia” live in the same apartment and hold down a variety of jobs (dishwasher, bike delivery guy, janitor), the jobs that actually make New York City run. The men play soccer on Sundays at a local park, but this is no casual pastime. They are good enough to have just won the semi-finals in the local season. The finals are just seven days away, and there’s pressure to find a replacement for a team member who hurt his knee. José, the best player and the unofficial team captain, delivers food for an upscale Mexican restaurant, careening around Brooklyn neighborhoods on his bike. When José’s boss (Christopher Gabriel Nùñez) informs José he has to work a private party at the restaurant the Sunday of the finals, José is in a bind. He keeps the bad news from his teammates, hoping he can figure out a solution before the game. He has plans to bring his pregnant wife (Loren Garcia) up from Mexico, and he can’t lose the job.

McKay, who also wrote the script, shows how all interactions tremble with possibilities (negative and positive). The power dynamic is completely skewed. It’s so clear José, although a trusted employee, does not feel comfortable saying to his boss, “Listen, I do a great job and I show up for you. I have something to do on my day off, you’ll have to find someone else.” His position, economically and otherwise, is too shaky to make demands like that. There is a sense of the complete instability in these men’s lives. One gets chased by cops for selling cotton candy without a permit; every interaction with police carries some threat of deportment. You never know who you’re dealing with. The vibe is: Keep your head down, don’t call attention to yourself. Even asking for a well-deserved day off is precarious. You are replaceable.

There is complexity in the film’s class critique. In delivering food, José runs into all kinds of people. There’s the receptionist in a gigantic marble lobby who speaks Spanish with him when he arrives to drop off food, but the second a group of businessmen stroll through, she switches to English. There’s the guy in front of an office building, in a suit and tie, who bonds with him about soccer, and is clearly Latino (they speak Spanish together), but, unlike Jose, has moved up out of the grinding gig economy. The divide is not just between immigrants and non-immigrants. The divide is between recent immigrants and those who have been in America longer. The gap seems unbridgeable.

McKay uses closeups of Cardona a lot, the camera watching him listen, think things through, worry. (This is, astonishingly, Cardona’s first credit.) The tension of José’s dilemma becomes almost unbearable, and it happens by stealth. With each interaction with his boss, José gets more and more frustrated, and less able to express it. Then there are quick cuts to José barreling through the streets on his bike, sometimes in the pouring rain, pedaling as furiously as he can. Each moment builds on the last, until you’re nearly out of your seat by the end. The soccer games are shot with a beautiful and fluid documentary feel, glimpses of faces, kids eating ice cream, New Yorkers chilling out after a long day at work, cheering, watching the game. You can see what these games mean, what leisure means, especially when everyone is working so hard, living on top of each other, not being able to plan for next week, let alone next year.

Along with the obvious nods to Italian neorealism, like (primarily) “Bicycle Thieves,” “En el Séptimo Dia” shares a lot of similarities with Majid Majidi’s “Children of Heaven,” in which a little boy accidentally loses his sister’s shoes and has to figure out a way to replace them, without alerting his parents. It’s a funny, smart film, with an exhilarating final sequence, but it’s also a biting class critique. Like “Children of Heaven,” “En el Séptimo Dia” plays like a bat out of hell. This is the kind of movie where you learn everything you need to know about a character not by listening to what he says, but by watching what he does. Everything José does has meaning, a point, and a purpose. There is nothing left over for him. For any of them. The biblical title echoes throughout. God “hallowed” the seventh day and “rested” because “Creation is followed by rest.” At least that’s the idea. If you work, you also get to rest. Any civilized person should agree.

By the time “En el Séptimo Dia” ends, you’ve been sucked into its energy completely, and you are hugely invested in José’s twofold quest to play in the finals and not lose his job. It’s really not too much to ask.