Something struck me as I started watching the moving documentary “Emanuel” and I had to remind myself of the details of the mass shooting that it chronicles: We used to be able to grieve these horrific events longer. I’m old enough to remember Columbine, and the details of that awful day felt burned in the national consciousness for years, but as the days in which we have to mourn those cut down by maniacs with guns have come to outnumber anything we could have imagined, one tragedy is replaced by another. Mass shootings in the United States have become commonplace. Director Brian Ivie doesn’t touch on this explicitly in “Emanuel.” It’s not that film, choosing to be more of a personal testimony about what happened in Charleston in 2015, yet can’t help but force viewers to think about what has transpired since that day, and hope that there is some way we can change. If we can’t stop events like the Emanuel Church shooting from happening, we can at least fix a broken system that allows them to be more easily forgotten.

On June 17, 2015, a sociopath opened the doors to a Bible study group at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina. He was welcomed in. As the group was ending, he stood up and revealed his true intent, opening fire on the black people in the room, killing eight of them right there (a ninth person would die en route to the hospital). It’s only a brief section of “Emanuel,” but one of the most disturbing things about the Roof case is how quickly this terrorist became radicalized. According to Ivie’s film, he was doing some research online after the Trayvon Martin case and basically came across racist propaganda, convincing himself that black people were taking over society. He wanted to start a race war.

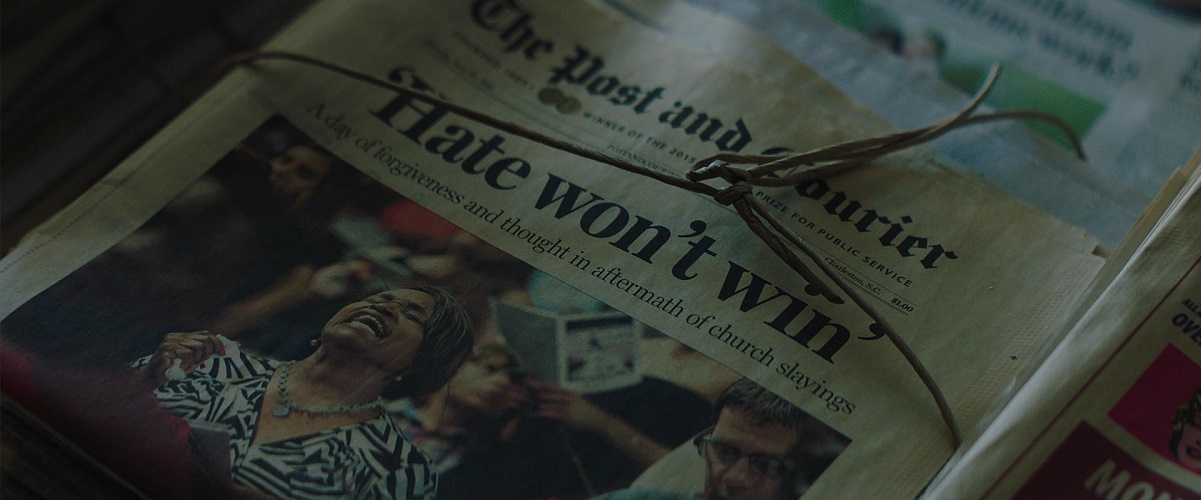

“Emanuel” is not really about Dylann Roof. It is about the survivors, and the relatives of those who did not survive. Its most effective passages are essentially testimonies from these people about the worst day of their life. It could be a woman talking about discovering that her mother had been shot or another describing actually being in the room and trying to save her kids. Ivie’s approach is empathetic and moving. We often criticize documentaries that are too “talking head,” but these testimonies are artfully shot and feel like an act of reclamation and forgiveness more than mere interview. And the structure of the film crescendos into a plea for forgiveness. Headlines were made when the families impacted by Roof’s actions claimed that they forgave him. This is a deeply religious film, clearly meant to convey the spiritual beliefs of the parishioners who were lost that day and their grieving loved ones (although it never loses its righteous anger in doing so).

“Emanuel” gets a little unfocused at times. There’s a section that moves almost randomly from a history of violence to Black Lives Matter to forgiveness to a brief piece on the removal of Confederate Flags in the area – it’s almost as if the film itself gets overwhelmed with all the issues it’s considering in the wake of such a tragedy. But Ivie brings it back to what’s clearly most important to the filmmaking team: forgiveness. The son of a victim, Chris Singleton, summarizes the film’s message in a proverb he first presumed was designed to encourage his baseball career but now thinks is about that awful June day: “If you fail in the face of adversity, you are a man of little strength.” He took it to mean that to succeed in the face of adversity, he would have to forgive Roof. I hope we can all figure out how to stop failing in the face of adversity as a country when it comes to gun violence, or we may find we have no more strength to give.